The Tragedy of Captain John

‘He lay like a warrior taking his rest,

With his martial cloak around him.’

We haven’t heard from our old friend D.W. Higgins for a while. Not for want of material, I assure you, as my file for this pioneer journalist and one of B.C.’s all time great storytellers continues to grow.

Pioneer journalist D.W. Higgins is back this week with another fascinating tale of pioneer days. —Author’s collection

While skimming my hit list for another Chronicle I keep passing one by that has always intrigued me, sad tale that it is. So, cutting to the chase, the story of a man whose dramatic fall from glory, but for Higgins, would be totally unknown to us today.

It’s a story that’s all the more disturbing in the dawn of Truth and Conciliation, one that I’m trying to tell with due sensitivity, as I explain in today’s Editorially Speaking...

* * * * *

“An Indian woman who has resided for nearly two years on William[s] Creek, and was commonly known by the sobriquet of ‘Captain John,’ died on Monday last from inflammation of the windpipe. This poor creature was the daughter of an Indian chief called ‘Captain John,’ who was shot in Victoria jail seven years ago...”

This is the brief obituary notice which appeared in the Victoria Colonist of July 8, 1867. Few readers of long ago would have linked the unfortunate woman with one of the saddest chapters in British Columbia history.

This particular tragedy had begun just nine years before, but memory—like conscience—can be one of convenience and likely few of those who knew the true story paused to consider.

To his credit, one who did reflect upon the unpleasant past, some 40 years after, was pioneer journalist D.W. Higgins whom we’ve met before in the Chronicles. He’d known the leading and supporting actors of this saga, including the remarkable character, Captain John, upon whose death only Higgins shed had a tear on behalf of the White community.

Once Captain John had been the most powerful chieftain on the north Pacific coast, boasting 3,000 Haida warriors under his command. About 40 years of age when Higgins met him, the chief with the unusual name cut an impressive figure. Although of average height, Captain John stood out from his fellow tribesmen.

“His sallow face was surrounded by luxuriant black whiskers, and his upper lip was adorned by a sweeping black moustache,” Higgins wrote. “His stature and his light complexion and the hirsute appendages gave rise to the impression that he was the son of a Russian and an Indian woman.”

Little was known of John's background but those details which Higgins had been able to learn were fascinating. It was common knowledge, for example, that, as an Alaskan youth, John had travelled to St. Petersburg in a Russian trading ship, remaining in the wintry city for two years before proceeding to London and home again by Hudson's Bay Co. vessel.

Marvelled Higgins, “He could read and write a little, and his language was a public puzzling maze of Russian, English, Chinese and Indian. With the aid of pantomimic gestures and broken language, he managed to make himself well understood.”

How John became chief of the Haida was a mystery even to Higgins, but chieftain he was. His word, garbled mixture of dialect though it may have been, was law. Thousands obeyed his every command.

Perhaps a good clue to John's secret as a leader was his sense of drama through which he acquired his unusual title. In fair weather and foul, he wore a uniform of long blue military overcoat, his wiry black hair crowned by a blue officer’s cap banded with gold lace. Upon meeting strangers, he’d pull himself erect, make a grotesque salute by pointing fore finger to his fine cap, and exclaim, “Me big chief!”

Then, introduction done, he’d swagger from the startled stranger “with an air of gloomy grandeur intended to impress the visitor with his importance”.

If the reaction of more sophisticated Whites were one of amusement, none let it show. “There was much that was absurd about Captain John's appearance but, taken for all in all, he was the finest specimen of the Indian I ever knew,” Higgins recalled.

Certainly his many subjects were impressed; to question John's authority meant severe punishment even death. The entire western shore of the Victoria waterfront, although settled by several Northern tribes, as well as the local Songhees, was virtually John's domain. Even the encamped ‘Stickeens,’ traditional enemies of the Haidas, avoided his wrath.

When 30,000 eager Whites had poured into Fort Victoria en route to the gold fields of the mainland, it was Captain John who’d kept his unruly followers in line, time and again preventing open bloodshed from erupting between the tribes and the arrogant Whites. Higgins even suspected John of having being in Hudson’s Bay Co. employ, so diligently had he maintained peace.

“One thing, is certain: to Captain John the Whites...were indebted for their immunity from harm.” None, he wrote, could deny that “had John been so minded, he could have let his wild army against the settlement”.

But the various tribes encamped on the far shore of the Inner Harbour faced a common enemy against which they had no defence: liquor. D.W. Higgins has left us one of the most graphic descriptions of the devil's brew which was to destroy both nation and culture.

By night, from the opposite shore of the Inner Harbour, whisky peddlers delivered bottled poison by the boatload. According to Higgins, they did so with the full knowledge of the city police. —Author’s collection

“The so-called whisky was the vilest stuff that the ingenuity of wicked-minded and avaricious white men ever concocted. What it was composed of was known only to the concocters. I was told that it was made of alcohol diluted with water toned up with an extract of red pepper and coloured so as to resemble the real thing. It was conveyed to the reserve under cover of night by boatloads.

“What the Indian wanted was something hot—something that would burn holes through his unaccustomed stomach and never stop burning holes until it reached his heels. Quality was not considered. The rotgut must be cheap as well as pungent, and these two elements being present, the sale was rapid and profitable.”

This was the lucrative trade conducted, under cover of night, by unscrupulous merchants who were respected leaders of the community by day. To the untutored Aboriginal, drink was a drug, a mind-bending elixir for which he would literally sell his soul. Daughters and wives were sold into prostitution; no sacrifice, it seemed, was too great for the firewater. Within months, the vast enchantments on the western harbour shore had become a brawling hive of degradation as proud warriors became stumbling drunks ready to commit acts of violence for another bottle.

Presiding over this carnage was the aloof figure of Captain John.

Finally, in the summer of 1860, violence erupted in the Haida camp. Several young men fired with drink announced their intention to drive the encroaching Whites into the sea. Realizing they couldn’t be calmed, John informed the drunken mob they’d be slaughtered by the Whites. However, he smiled, if they were spoiling for a fight—why didn't they attack their old enemies, the Stikines?

That evening near where Johnson Street Bridge spans the Inner Harbour today a Haida primed with bad whisky encountered a Stikine youth on the road. When the boy’s decapitated body was found both tribes prepared for war by digging trenches and erecting log fortifications and, over the next three days, waged a bitter gun battle. Musket get shots punctuated the usual calm around the clock as Victoria authorities remained neutral.

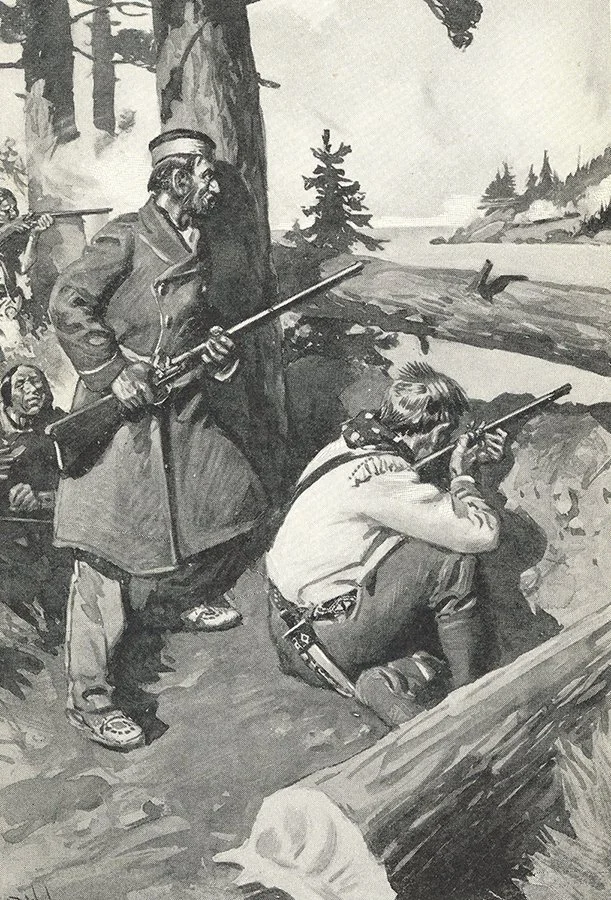

On the third day of hostilities, a Sunday, Higgins and several fellow adventurers decided to visit Captain John's “fort."

“We watched our opportunity, and by keeping well behind the standing timber that then thickly covered the reserve and by dodging from tree to tree, we managed to reach the Captain's quarters without injury.”

Captain John and his men exchanging fire with their enemies, the Stikines (/stəˈkiːn/). —Author’s collection

Secure behind the height of breastworks, Higgins faced a short lecture on his foolhardiness from John. But the chief soon changed the subject for he had other things on his mind—“he was anxious to know what the [news]papers said about the fight, and I told him, much to his satisfaction, that they reported that he was getting the better of the Stikines. He was very grave and serious in his demeanour and seemed to feel that a great responsibility rested upon him."

With dark, Higgins and companions crept from John’s fort. Some distance from the trail, they met two men helping a third, who was in great pain. The injured man's knee had been shattered by a musket ball and the adventurers helped to rush him to the hospital where, the following day, his leg was amputated.

It was this incident that finally aroused official ire. With a strong force of heavily-armed police and marines from HMS Hecate, Police Magistrate Augustus Pemberton marched into the battle zone and arrested leaders of both sides, including a bewildered Captain John, and destroyed the fortifications.

After being “soundly lectured," all combatants were released and a sullen peace reigned in the camps.

But the flow of vile liquor continued unabated. From the wholesale liquor import warehouses at the foot of Johnson Street thousands of gallons of the illicit brew were smuggled by night across the harbour where eager customers waited in line to pay hard cash for slow death. The addicted clientele paid a dollar a bottle; each sale of the diluted rotgut meant a 90 percent profit for the peddler.

“Did the police know that this Infamous business was being carried on under their eyes and noses?" Higgins asked his readers in 1904, then answered: “They were well aware of the methods by which the Indians were being cleared off the face of the earth."

The former editor and MLA charged that all city police officers of the day had been “taken care of". While other forms of crime had been diligently investigated, the respected owners of the Johnson Street warehouses had continued business as usual, their sloops, rowboats and dugouts ferrying cargo after cargo across the darkened harbour waters.

The bootleggers, said Higgins, were immune and justice was not only blind but so deaf that she couldn’t “hear the plaintiff cries of the wretched victims of man's greed and rapacity as they rent the night air and seemed to call down heaven's vengeance upon their poisoners”.

But divine justice, like that of mortal man, was also blind, and the steady slaughter of an ignorant people marched unchecked. Where once reason and an advanced culture had ruled, "debauchery, outrage and death” now prevailed; not only on the far shore of the Inner Harbour, but along the length of the West Coast. From Washington Territory to Alaska, “tangeleg” whisky stalked man, woman and child.

What this whisky began, disease ended and the heavy hand of British justice proved little deterrent against the resulting crime wave.

Throughout this stormy period, Captain John had resisted temptation. Finally, he too became a steady customer of the Johnson Street warehouses. Without his authority, the Haidas ran rampant. Murder and violence became everyday occurrences, Higgins listing one outrage after another.

“I might continue to cite tragedy after tragedy which resulted directly from the sale of liquor to the poor red man by white men who worked under the actual protection of the constabulary. But the instances I have given will suffice to show the condition of things that prevailed in and around this Christian town, beneath the shadow of church spires and within earshot and stone's throw of the peaceful and happy homes of pioneer settlers."

By now even Captain John had become addicted. Once he’d been level-headed and cunning; now his mind was benumbed by all-powerful drink. He’d been handsome and dignified; now he was a “besotted, quarrelsome creature," his fine blue greatcoat soiled and tattered.

Finally came the day when the schooner Royal Charlie was fired upon from the Haida village while sailing out of the harbour. Victoria constables—the same constables who were deaf dumb and blind when it came to investigating the organized liquor traffic—promptly marched into the village and arrested Captain John and a brother.

The chief had submitted meekly until an officer started to search him in the Bastion Square Police Barracks. Suddenly, John drew a knife and slashed wildly at the nearest constable, his brother doing the same. A split second later both were shot dead.

The Bastion Square Police Barracks, centre, where Captain John and his brother were fatally wounded. —BC Archives

Half an hour after, Higgins arrived on the scene to find both men where they’d fallen. Someone had covered John with his shabby overcoat and placed his old officer's cap, the one with the gold braid, over his face. Raising the cap, the journalist “gazed long at the features which were placid and peaceful in death.

“Something of the old-time nobleness lingered there and his coal-black eyes, which were still open, seemed to gaze sadly, if not reproachfully, into mine. As I replaced the cap, these words from Wolfe's great poem occurred to me:

‘He lay like a warrior taking his rest,

With his martial cloak around him.’

So ended the tragic career of Captain John. Much has been written about the ravages of smallpox that killed Indigenous people by the 10s of 1000s, sometimes transforming villages into ghost towns almost overnight. If Chronicles readers find it difficult to accept D.W. Higgins’s appalling account of 1904, they need only to consult many irreproachable public records in the Provincial Archives to confirm this calendar of horror.

Anthropologist Wilson Duff, in The Impact of the White Man, cites disease, particularly smallpox, as B.C. First Nations’ greatest enemy. One epidemic, which began in Victoria with the arrival of an ailing White from San Francisco, raged throughout the province for over two years.

Within that short period, it's estimated that one-third of the Indigenous population—almost 20,000 souls—perished.

But the devastating effects of liquor, physically, psychologically and spiritualy, can’t be refuted. More than epidemic, more than the White man's advanced ways, liquor destroyed the complex Indian culture, his integrity and independence. Poor Captain John was but one victim of 1000s.

Abetted by the ignorant and poisoned by the profiteer, he and ill-fated brothers form one of the most ignoble chapters in provincial history.

It's a poor enough distinction and one of which, even today, we should be ashamed.