The Weaker Sex

In last week’s Chronicles the late Ozzie Hutchings, machinist and liquor store clerk by trade, told the suspenseful tale of Old Growler, the ‘Phantom of the Unuk.’

Ozzie, retired when I met him in 1970, was an historian by choice and a born storyteller. I’m blessed to have his files and 100s of photos of the ghost town of Anyox and of Stewart, B.C.

With my help in the early ‘70s Ozzie wrote a series of articles for the weekend magazine section of The Daily Colonist, telling of the mining activity in the province’s northwestern corner and the colourful characters he’d met before moving to Victoria where he eventually retired after years with the B.C. Liquor Control Board.

I also published a couple of his articles in Canada West magazine when I was its co-owner and editor.

A matched team of horses hauling a wagon on the main street of Stewart, B.C., 1911. It was still wilderness country, 20 years later, when young Anna Ullman set out on the overland hike that would almost cost her her life. —Courtesy Ozzie Hutchings

One of his best stories is that of Anna Ullman, a young woman who unwittingly took a page from the legendary solo trek of Lillian Alling, overland through B.C. and Alaska to Siberia. (Another story for another time.)

Anna wasn’t quite so ambitious; she merely set out to hike the Yukon Telegraph line from Hazelton to Telegraph Creek in 1932.

Her yen “to see what she could of the country and its people” almost cost her her life. Foolish she may have been, but no one questioned her courage when they heard her incredible story while she was recuperating in hospital.

So, over to Ozzie Hutchings:

* * * * *

When Jack Dodd and his brother Dan arrived in Stewart, on Sept. 29, 1932, they’d taken three weeks to walk from Telegraph Creek to Hazelton via the old Yukon Telegraph Trail. Asked as to their trip, Jack replied that, overall, they’d made good time although they’d had to travel miles out of their way due to high water from heavy rains, and the fact that some of the abandoned cable crossings were becoming dangerous.

Yet, at a point 35 miles south of Telegraph Creek, they’d met a Miss French who told them she’d walked from New York City with 40 pounds on her back!

She was headed along the trail to Atlin, Whitehorse and Skagway where she planned to catch a steamer for the south then return to New York and write the story of her adventures in the northern wilds.

Two days later, 100 miles south of Telegraph, when camped for lunch, they encountered a second young woman on the trail, this time a Canadian named Anna Ullman, who paused briefly before continuing northward. She also had about 40 pounds in her pack.

Both of these girls, said Jack, seemed to be fit and “good mushers.”

It seems that Miss Ullman had been in training as a nurse. However, being very interested in the Indigenous peoples of the north country, and reading that Hazelton was the centre of a large group of Native people, as well as being the supply depot for the famous Yukon Telegraph trail, she’d decided to see for herself—and hitch-hiked from Vancouver to Hazelton, some 1000 miles.

She’d planned to follow the tail from Hazelton to Telegraph Creek to see what she could see of the country and its people. The day after her arrival in Hazelton, she headed for the first cabin on the Telegraph line, 30 miles distant.

However, not making it, she camped under the trees, using cedar boughs and a groundsheet for a bed. She made the cabin the next day, where a provincial police constable from Hazelton caught up with her and warned her that to travel farther at that time of year (early May) was too dangerous due to the heavy rains and melting snow in the mountains.

Miss Ullman wisely returned with the constable to Hazelton where, with the lawman’s help, she found a job as a cook.

It was there, at the George Biernes ranch, that Anna learned how to prepare fancy foods for men on the trail—such gourmet dishes as Mulligan stew, baked beans and bacon, sourdough bread, flapjacks and whatever meat could be shot on the hoof.

She also came to know the different human, equine and canine types who worked with the pack trains, taking supplies in to the men who maintained the Yukon (by this time the Dominion) Telegraph line. Anna remained at the ranch for three months, enjoying every minute of her stay and making many friends while in the field with the pack trains.

About the end of July, she pulled up stakes and headed once more on her northern journey.

The trail became nasty again as there had been considerable rainfall which created more mud and swamp with which to contend. While on her way, she met up with some friends, members of the Simon Gun-an-Noot family, who invited her to share breakfast with them. This, she’d later rate as one of the highlights of her journey.

From this point the weather deteriorated. Anna plowed onward through the rain and slept at night in whatever refuge’s cabin she could reach, these having been spaced along the telegraph line for the purpose. The Blackwater Lake lineman reported that he and a friend were working on a new cabin when Anna came upon them.

She was wet through to the skin and the men went on with their work while she changed her clothes in their shelter.

After she washed her dirty clothes in the creek they had a hot supper and spent the evening talking until bedtime, when the men retired to their tent, Anna taking the shelter.

As the men were moving on next day, they loaned Anna a horse for the stretch of line to the next camp, 25-odd miles distant. From there, she continued on her own, through more mud and high water. How she ever navigated some of these cable crossings we’ll never know, as the Dodd boys were forced to bypass some as being too rickety. The Nass River crossing, however, was in good shape.

The linesmen along that section had been alerted to watch for Anna and, with their assistance, she was able to complete her 400-mile trek through that vast, rugged country during some of the worst rainstorms witnessed in this territory for many years. Finally, this plucky young woman reached her goal, Telegraph Creek, on the Stikine River.

After a hot bath, change of clothing, some good home cooking and a few days’ rest, Anna decided to stay on for a while, meet the people and take some photographs of the winter scenery.

Later she moved to a ranch north of Telegraph Creek where she helped a large family with the cooking and accompanied them on hunting and trapping trips when they camped in tents and used snowshoes. As there was much wildlife in this area, she saw a large variety of pelts skinned and dried.

As Anna wanted to take some special pictures, she left the camp and headed up to Jim Town after a slight snowfall. She camped that night in a cabin. The next morning, it was snowing hard. When, on the third day, it cleared up, she decided to cut cross-country to meet up with the mail carrier. But they didn’t meet and she left a note on a trail marker explaining that she was “making for Sheslay and should be back within a week”. (This was some 30 miles north of Telegraph Creek.)

By this time she’d learned a good deal abut handling herself in the bush, but this was different, bucking heavy snow on snowshoes.

She made for the river and tried her luck on the ice, keeping an eye on the telegraph line when she could. By nightfall she was a long way from a good campsite and decided to head up the bank and find the trail among the trees so as to get out of a strong north wind.

To her surprise, she heard a dog barking to the north and concluded that she must be near an Indian camp. She was now having a hard struggle, as the ice was broken up in places and she was tired, cold and hungry.

The dog’s barking grew louder. When she rounded a bend in the river, the dog turned out to be a coyote making his way from the trees to the river and dragging a trap. It was a nasty sight and she regretted not having a gun with which to put the animal out of its misery.

She finally climbed the bank and, in the trees, made camp. Using a roll of photographic film to start a fire, she thawed some chocolate bars and rolled herself up in a blanket for the night. In the morning she intended to find the telegraph trail and return to the ranch. The next day, she headed down the river, thinking it would be the easiest route, but after a while she came to holes in the ice, then to a canyon with steep, icy sides.

On one side there was a ledge, about two feet wide, and she worked her way along, one foot at a time.

Suddenly, a splash behind her made her stop in her tracks—the ice under her right snowshoe had given way and only half the shoe was supporting her. The left foot was on firm ice and, carefully, she lifted he right foot and removed the snowshoe, putting it over one arm. Then she shuffled the rest of the way to solid ice.

At this point, the ice became treacherous; as she climbed from one chunk to another, there was a splash and a large cake broke away from the main sheet. Anna held onto this for dear life, terrified lest her icy platform be sucked under the ice field, taking her with it.

With all her strength, she grabbed the solid shore ice and slowly dragged herself to safety. The cold was overpowering but she was able to watch with relief as her “raft” vanished under the main river ice.

By this time, she was all in. While resting on the river bank, she realized that she must go down the river and find the telegraph line—and quickly, as time was running out. She’d forgotten how long she’d been held up in the canyon, even the number of days she’d been on the trail. Her food and precious matches were now in short supply and she was becoming steadily weaker, but she kept going.

The next day, while resting, instead of sucking on a piece ice, she removed her snowshoes and crept to the open river for a drink. As she neared the edge, the ice cracked and submerged both her feet. Ice immediately formed on her moccasins and her feet became increasingly cold and stiff.

Anna had been fighting for days and fatigue was taking its toll, but she knew that her only hope lay in her getting back on the trail.

After making another strenuous effort to do so, she was so weak that she had to discard her pack and blanket. Lightened of her pack, she made better time and she came to a frozen jam in the river, about eight feet in height. Removing her snowshoes, she threw them over the barrier and, after many attempts, succeeded in scaling the wall of ice, where she lay on her snowshoes for a short rest.

Then she was on her way once more when, looking downriver, she was relieved to notice that the going was becoming easier as the river widened. Then, in the distance, she saw a bridge, then a telegraph pole. She’d made it to the trail!

Climbing up the steep bank consumed most of he remaining strength but, encouraged at having found the main trail, she headed southward to Telegraph Creek after another rest.

The going was hard due to the snow and she rested often. Finally, she became so tired that she lay down beside a log, exhausted, and fell asleep.

That sleep might well have cost Anna her life had it not been for trapper Joe Coburn. Passing by, he saw her, shook her until she awakened, then carried the half-dead girl to his sleigh. Making her as comfortable as he could, he mushed his dog team onward as fast as they could go. Once in camp, he and his people tried to thaw her out, but with little success, so they rushed her 16 miles to Telegraph Creek.

This summer photo does little to convey what it must have been like for Anna Ullman during the unusually wet summer of 1932 followed by an early winter. —https://explorenorthblog.com/the-trip-to-telegraph-creek-bc

Upon arrival, it was realized that Anna was in extremely serious condition and a call for help was sent out over the wire to Norman Forrester and Paul Davidson of Carcross, who flew Anna to the Atlin hospital.

There, Dr. D’Easum, his assistant Ida Lind and Mable Peto performed an emergency operation which saved Anna’s life but cost her both her feet.

While waiting for the plane at Telegraph, Provincial Police Const. Devlin and his wife, and Mr. Tipton of the Hudson’s Bay Co., did everything they could to relieve her pain and make her comfortable.

While convalescing at Atlin, Anna said that there were times that she didn’t wish to see anyone and, at night, as she began to drowse off, “many things” went though her mind: sleigh dogs, northern lights, big game animals, music, snow and ice in the canyon, people dressed like trappers, flowers and airplanes.

Once asleep, these jumbled images became nightmares and, often, she awoke screaming.

This courageous 19-year-old girl finally moved to Vancouver where, I understand, she was fitted with artificial feet. A year later, she visited her friends in Hazelton. They told her that she’d fought and lived through an ordeal which would have killed some of the strongest of men.

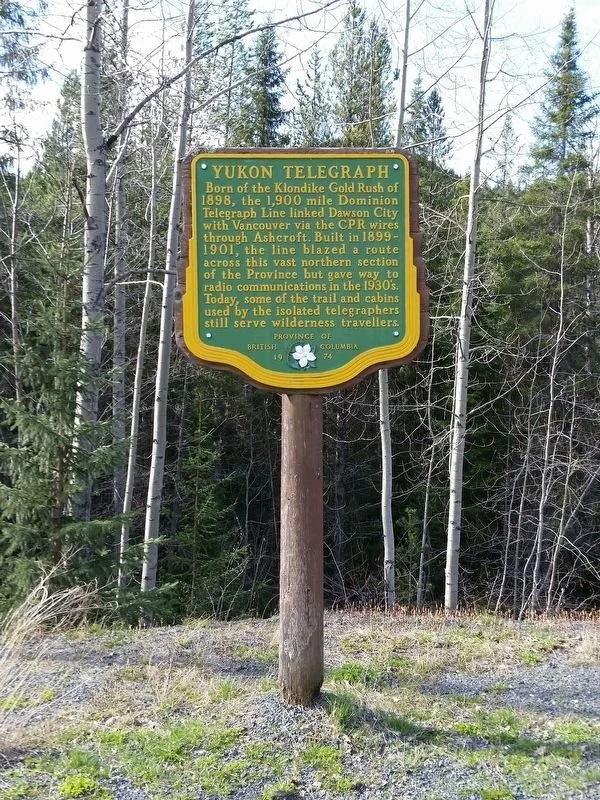

A signboard commemorating the historic Yukon/Dominion Telegraph Line. —Hmdb.org (The Historical Marker Database)

* * * * *

According to the Find a Grave website, there’s a headstone in Ross Park Cemetery, Flin Flon, Manitoba, for an Anna Ullman (18 Oct 1910-22 Mar 1949). Meaning that this Anna Ullman was just 38 when she died and would have been 22 years old in 1932. Author Hutchings gives the age of the Anna Ullman of his story as 19 at the time of her adventure. Could this be the same Anna?

* * * * *

For the truly incredible story of a young Russian woman who set out to hike overland from New York City to Siberia, just Google Lillian Alling. When last seen, she was in Alaska. To this day, some believe she actually made it to her homeland!

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.