Through the Amazing Lens of Amazing Hannah Maynard

As a lifelong practitioner of the written word, it galls me to have to admit the truth of that old expression, “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

But, as that more modern saying goes, “It is what it is.”

I’ve been thinking about what photography has meant to recording history and how it has ultimately changed our lives. After primitive beginnings such as the daguerreotype and tintypes came the cumbersome large-format camera that required a tripod to hold it still for its slow exposures, followed by messy wet processing in a darkroom.

All of this required a strong work ethic not to mention artistry.

Triplets? No, an example of Hannah’s wizardry in the darkroom. Before the computer and Photoshop (and now AI) made such image manipulation easy and almost painless, this was really challenging. More than that, it was thinking outside the box. —BC Archives

Today, it’s a cultural phenomenon: pocket-sized cameras, smart phones and computers with their instantaneous and effortless imagery—just point and click. Absolutely anyone can take a decent photo today and capture not just scenes and portraits but events as they’re occurring.

But it has been a long road and many of the greatest photographs of the past century and a-half were taken with difficulty, sometimes at great personal risk, and involved not only talent and skill but intensive thought and effort. Thus it’s only right that some pioneer photographers have achieved near-legendary status.

One of them is British Columbia’s own remarkable Hannah Maynard, a true photographic innovator who broke new ground with her artistic experimentation.

* * * * *

Hannah Maynard (1834-1918), nee Hannah Hatherly, wasn’t the only photographer in the family, husband Richard James (1832-1907) having followed her lead two years or so later. He favoured landscapes whereas Hannah preferred to take portraiture in her studio in Victoria—as well as, from 1897 on, the Victoria Police Department’s first mugshots.

This Hannah Maynard portrait of a young woman in a wild hat wasn’t taken in her studio, but at the Victoria Police station where Belle Adams had been charged with murdering her lover with a straight razor. —BC Archives

Read more about The Tragedy of Belle Adams…

Prior to coming to Victoria, the Maynards had immigrated to Canada via Ontario where Richard had a boot and shoe shop before answering the call to the Cariboo gold rush.

By 1862, they were in Victoria and Hannah, obviously a woman of determination, had opened her studio, Mrs. R. Maynard’s Photographic Gallery. It’s thought that Hannah, a wife and mother in an age when women were expected to be homemakers, no more no less, acquired the skills of her chosen profession while in Ontario. We don’t know what drew her to photography, then an ambitious goal and one totally uncharacteristic of a Victorian (as in the age of Queen Victoria) woman. Whatever, she soon shared her new skill with Richard.

By 1864, upon their settling in Victoria, Richard was shooting his first landscapes of the city’s waterfront and on his way to becoming a professional landscapist.

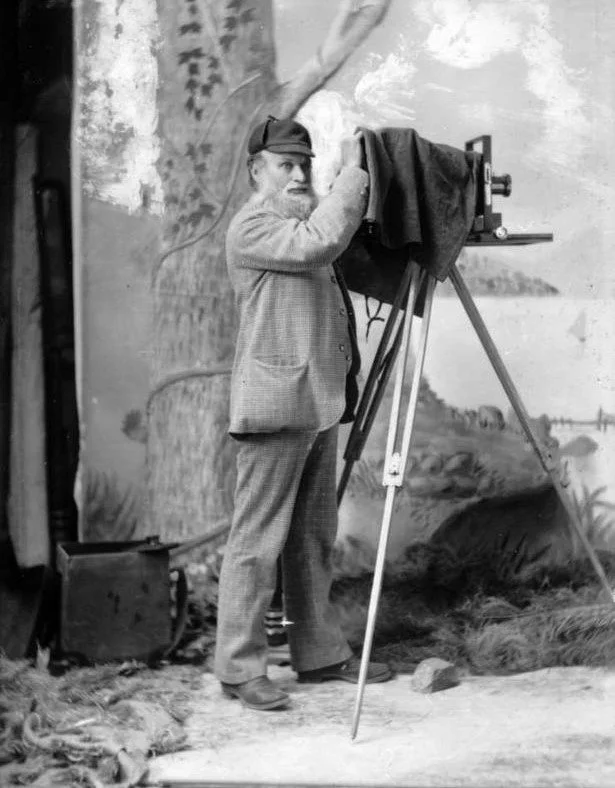

An older Richard Maynard in a studio shot. —BC Archives

He preferred to work behind the lens and outdoors, sometimes for clients such as the CPR, and carried his gear to the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii) and the distant Pribilof Islands, Alaska.

Note the cumbersome camera and tripod. Hannah used the same awkward equipment but had the advantage of working indoors with her darkroom close to hand except when she accompanied Richard on his photo expeditions to Haida Gwaii and Banff. (Landscape photographers often had to develop and print their photos in the field (and in almost total artificial darkness, by the way).

Large-format cameras produced large negatives and contact prints which explains their “high resolution” as we judge digital photos by today. Many of these old photos can be enlarged to billboard size without losing visible quality!

Hannah’s bread and butter were the portraits commissioned by prominent Victoria families. Such as these:

Two examples of Hannah’s studio portraits, businessman Joseph L. Loewen and Mrs. Allen Francis, wife of the United States Consul. (Note that she’s identified by her husband’s first name rather than her own, as was long the practice). —BC Archives

Another interesting portrait, this one of Mrs. Florence Gillespie and her son John Hebden.

What are they looking at? —BC Archives

How about these three lads in their sailor suits?

As for these little girls, likely sisters, is the one on the left about to fall asleep? If you’re wondering, the little boy is petting Hannah’s stuffed one-eyed wolverine!

Besides police mug shots, Hannah also captured on film some of the leading citizens of her day; below is Lady Amelia Douglas, wife of B.C. colonial governor Sir James Douglas, with a grandchild.

I’ve taken the liberty of slightly cropping some photos so as to better fit our Chronicles format.

When Hannah posed (via darkroom magic) with her own grandson, she was experimenting with composite imagery. —BC Archives

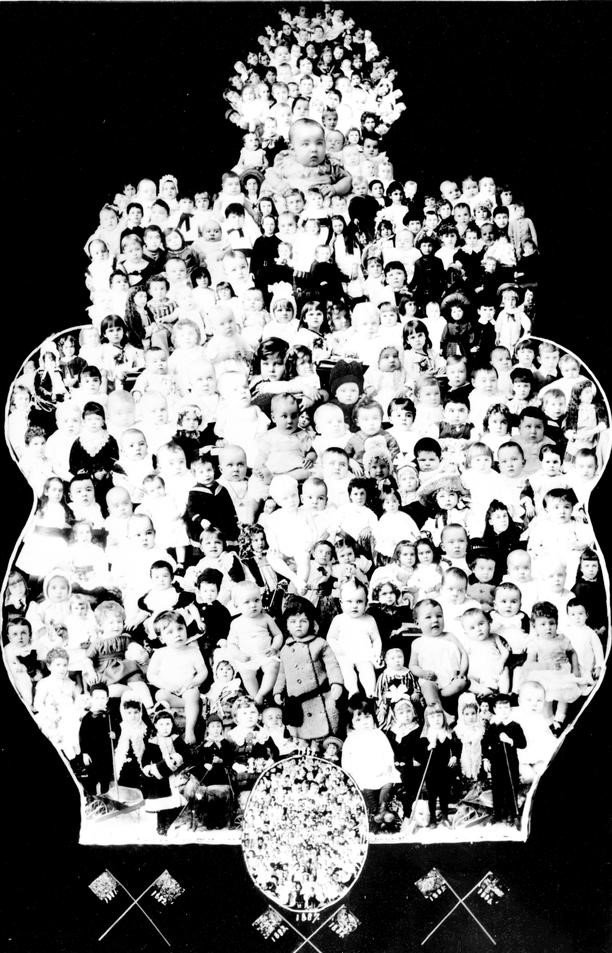

By far her most ambitious composite photos—photos which required untold hours of work—were those of the city’s newborn babies she dubbed ”British Columbia Gems.” Each New Year, each and every one of these portraits which she’d taken through the calendar year were individually pasted in a montage then printed on heavy card stock known as ‘carte de visites,’ and later as cabinet cards.

Remember: Hannah didn’t enjoy the ease of cut-and-paste on a computer. This was time-consuming and tedious work!

Have you ever played, Count the jellybeans in the jar? Try guessing how many children are in this photo! The British Columbia Archives caption reads: "’British Columbia Gems of the Year 1883’; composite photo made from the children's portraits taken the previous year; at centre are the Gems of 1881 and 1882.” Hannah gave these out as greeting cards. It has been estimated that, in total, her printed “Gems” numbered 22,000!

Personal Note: I spent many, many an hour in a darkroom in years past. Even with that firsthand experience I can only guess at the hours it took for Hannah to create this photographic masterpiece.

And this one. As you can see, she’s taking her experiment further by framing the children’s portraits on an artist’s palette.

Again:

We known the Maynard household included birds because they show up in several self portraits, as in this one with her daughter:

Here’s another self portrait, this time as one of a series ‘photo sculptures’. Note that, never once, did Hannah smile for the camera. But, then, neither did any of her other subjects—that’s the way it was done in the Victorian era.

—BC Archives

Hannah Maynard achieved yet another milestone by operating her photo studio for no less than half a century. Identifying her gender in her signage had to have been intentional—a heads-up to chauvinistic clients in that masculine age who’d otherwise have been disappointed, even disgruntled, to discover that this professional photographer wore a skirt.

Happily for posterity, Hannah’s genius with a camera and in her darkroom prevailed and she gained a professional reputation on both sides of the border, and as far east as, at least, Winnipeg. There, in 1888, a newspaper extolled: “...Her photographic work cannot be excelled for brilliancy of expression and harmony of effect...she is recognized as one of the foremost representatives of the profession in the country.”

Upon her retirement in September 1912 the age of 78—five years after Richard’s passing and six years before her own—Hannah could proudly tell a Colonist reporter, “I think I can say with every confidence that we photographed everyone in [Victoria] at one time or another.”

In latter years she has been praised for her having consistently demonstrated “uncommon sensitivity, emotional depth and subtle humour”.

As for her numerous “selfies,”, was this her ego speaking? Or simply the fact she required a willing model, besides her own five children, to experiment with? Hints of her grieving over the deaths of two teenage daughters and her flirtation with seances and spiritualism show in some of her later studio experiments. In her diary, however, Hannah never let her emotions show; she was always terse and to the point.

It’s interesting to note that from 1897 on there was no more artistic experimentation, it was just pure business.

The amazing Hannah Maynard on two wheels—probably one of the rare occasions that she wasn’t working in her studio and darkroom. —BC Archives