Tombstone Tales - A Virtual Tour of Mount View Cemetery

I remember, years ago, a North Cowichan mayor saying, “People come first.”

Meaning, human wants and needs trump environmental values every time.

As you may have seen in the news, and in last week’s Chronicle, North Cowichan Municipality is looking to expand Mountain View Cemetery into an adjoining forest of mature fir and maple trees—proving that even dead people come first.

As should surprise no one, I’m a dedicated fan of cemeteries, even having written the book telling the history of the Valley’s public graveyards. Which inspired me to check North Cowichan’s website and to go along to the open house, two weeks ago.

There weren’t many there; besides Municipal staff, most of those present were immediate neighbours on Drinkwater Road who are concerned for the loss of their forested backyards. There’s still room for burials in the Valley’s only non-denominational cemetery, and more and more people are choosing to be cremated, which allows for up to six headstones in place of a single traditional grave.

But, for all our New Age environmental enlightenment, “people come first” and you can bet your life that the cemetery’s expansion, to be done over a period of years, whatever the cost to trees and wildlife, is a go.

Here then, for Chronicles readers who haven’t read Tales the Tombstones Tell: A Walking Guide to Cemeteries in the Cowichan Valley, the story of Cowichan Valley’s largest—and growing—cemetery.

* * * * *

It was pretty hard to miss it. I had passed it by every few days or so for years, always with the nagging thought that I had not really “done it,” for all of my weakness for cemeteries. Only when I was asked to give a tour to a group of local history buffs, in the spring of 2009, did I make the effort to become acquainted with Mountain View Cemetery. Now I am glad I did–there are some great stories in Mountain View.

Beginning with its origin not as a municipal cemetery but as the site and cemetery of the Somenos Methodist Church from 1926 until its de-consecration and demolition. A plaque tells us, “On this site and on these stones stood the Methodist church of Somenos. Erected 1878. Dismantled 1946. Municipality of North Cowichan Cemetery. Founded by the Methodist Church 1878. Transferred to United Church 1926. Became property of the Municipality 1962.”

The cairn denoting that this was the site of Somenos Methodist Church.

North Cowichan had been a reluctant suitor, the issue of a non-denominational cemetery having arisen as far back as 1900 when it was proposed, but rejected, that five acres be acquired for this purpose. In 1909 the Cowichan Leader urged the Municipality to acquire land for a cemetery, “something which will have to be done sooner or later…The idea of converting every church yard in the district into a burying ground is not to be commended and does not enhance the value of the surrounding land. The sooner Council takes some action regarding this matter the better.”

In 1913 the newly-incorporated City of Duncan negotiated to buy the land but found that the previous owner had prohibited its use for this purpose as a condition of sale. The matter was still up in the air four years later when the wealthy Sir Clive Phillipps-Wolley, master of ‘The Grange’ just up Drinkwater Road, wrote one of his acerbic letters to the editor. In this one he decried expansion of the Methodist Cemetery (with neighbouring St. Mary’s, Somenos Cemetery) as a “depressing prospect” for travellers using Somenos Road which then served as the Island Highway. It is more likely that he was concerned with the prospect of depressed property values.

Not until the 1930s was land adjacent to the existing Methodist cemetery acquired for this purpose. The combined cemeteries, the land for the original having been donated by Archibald Kier who, three years later, became its first resident, now covers 14.7 acres (of which 12.5 acres are suitable for burials). The distinction between the new and old sections of Mountain View is made apparent by the fact that there are upright headstones only in the pioneer section, it now being the practice, by provincial statute, to permit only “lawn style” (flat) memorial plaques.

Although not torn down until 1946, general usage of the church ceased in 1928; funerals continued a further nine years, the last being that of the church steward, J.H. Smith.

Most eye-catching is the south west corner, immediately adjacent the Drinkwater-Somenos roundabout. This is the oldest, most prestigious section with the imposing headstones that have come to symbolise the Victorian and Edwardian eras. For those families who had the money to spend on immortalising their dead, anyway. For those so inclined, this still holds true for this section only: “Memorials in the remainder of the…cemetery must be installed with their top surface level and flush with the surface of the ground. All grave markers or memorials must be of the tablet variety made of stone or bronze. Bronze memorials must have a three-inch-thick concrete or stone base, and all memorials, whether of stone or bronze, must conform with [specified dimensions]. No grave, or grave space shall be defined by a fence, railing, curbing, hedge, or other marking save by a memorial marker, tablet or monument as set out in Section 18 “of Bylaw No. 2933”. Two other options are memorial trees and, for ashes, Columbaria. At the time of writing, North Cowichan Council was seeking public input into the possibility of permitting green burials.

Something that is apparent in most ‘frontier’ cemeteries such as those of the Cowichan Valley is the disproportionate number (by today’s standards) of children’s graves, the sad result of then untreatable childhood diseases and before the advent of antibiotics. Many young women died of complications during or post childbirth. Adult males were subject to occupational and recreational mishaps. Hence so many tombstones indeed have tales to tell.

You will find several impressive markers for the pioneer Kier family, including that of the patriarch, Archibald Renfrew Kier, aged 84 years and five months. And that “Sacred to the memory of Harriet Elizabeth, beloved wife of James Kier. A native of Ont. Born May 30th 1862 died July 4th 1886. A wife so kind, a friend sincere. A gentle mother to her children dear. Her life was asked, but God denied, And brought her gently to His side.” Her death followed that of son Norman James Kier, aged five years, by just three months. Perhaps it is as well that she was spared the grief of losing her daughter, too, Olive Isabella Bernice Kier passing away eight months later, aged seven years and three months.

Upon his death in January 1934, it was said of George Archibald Kier, that he had “lived here longer than any other settler,” having accompanied his parents from Ontario at the age of seven. He had attended the Valley’s first school and held the first police appointment in the district upon being appointed by Premier William Smithe in 1884. According to his obituary, “In 1886 Mr. Kier brought credit to himself when he captured the Indian who perpetrated the double murder of William Dring and Miller at Crofton.” (This story is told in the chapter on St. Peter’s, Quamichan.) He also played a role in the Mount Sicker boom by working as a freighter, hauling equipment and goods to the copper mines. After marrying Florence Monk he managed a store at Somenos for G.T. Corfield before making farming the balance of his life’s work from about 1905 on. At the time of his death he left a widow and eight children, among them Sgt. William Kier of the Provincial Police. His funeral, well attended, included a delegation of provincial police officers consisting of the assistant commissioner and nine officers and constables from Victoria and Valley detachments.

Georgina Kier Trott, 1891-1924.

Another family member is Georgina Kier Trott, 1891-1924. Her drowning, and that of John Riley, in Cowichan Lake was all the more newsworthy because of the heroism of her 12-year-old niece, Dorothy Kier. Riley had taken Mrs. Trott, Dorothy, 14-year-old Cale Jarvis of Vancouver and two dogs in his small boat to Bear Lake. Upon the return trip he swung by Goat Island so the children, who were vacationing at the lake, could see the goats. But as Riley resumed course for town, they struck a half-submerged log with such force that the boat was impaled and its uplifted bow forced the stern under water, choking the motor.

With the boat rapidly settling by the stern and the children’s screaming, Riley instructed everyone to swim for shore, 150-200 yards distant. Dorothy removed almost all her clothes and Cale shed his boots and socks. Both adults were good swimmers but were constrained, perhaps by modesty, from following suit.

Almost immediately, Riley was in trouble and, only a short distance from the sinking launch, slipped under. Mrs. Trott made it halfway to shore before she began to flounder and, calling to Dorothy that she could not go on, she, too, went down. Dorothy, who had had the foresight to take a board from the boat as a float, passed it to Cale who was a poor swimmer and also beginning to struggle.

By this time help was on its way, attracted by their screams before they abandoned ship, and Cale was soon picked up, Dorothy making it to shore unaided. There was no sign of the adults.

The double irony of the boat having remained partially afloat and both adults drowning despite having been good swimmers and despite rescuers having arrived on the scene in minutes was particularly painful for families and friends to bear.

“Quite a gloom has been cast over the district by the tragedy,” reported the Cowichan Leader. “The happy disposition of Mrs. Trott had endeared her to many and there were tears in strong men’s eyes as they went to search for the bodies, directed by Dorothy to the places she indicated the bodies had disappeared.”

The single redeeming feature of the tragedy was the coolness displayed by “the bright little flaxen haired girl” in removing her clothing, clutching a board and then giving it to her friend. She had only learned to swim the summer before. Rescuers credited the board with keeping Cale afloat.

Although badly shaken by her ordeal, Dorothy was able to tell a newspaper reporter of the frantic minutes immediately following the collision, how Mrs. Trott had sternly warned the children not to “grab each other” and how, after both adults disappeared, only her aunt’s hat remained floating on the water.

A further irony was the fact that Provincial Police Constable William Kier, who conducted the search for the bodies, was Georgina Trott’s brother. She was just 33. Friend John Riley, an Australian who had arrived in the Cowichan Valley in 1913 and served overseas during the First World War, was 45 years old.

The following June, in a ceremony held at the Queen Margaret’s School assembly hall, an overflowing crowd watched as the Rev. Arthur Bischlager, district Scout Commissioner, presented Dorothy with a Girl Guide lifesaving medal. Then, escorted by Iris Stock, her patrol leader, Dorothy was led to the stage. As Bischlager pinned the medal, a silver cross with trefoil design suspended by a blue ribbon, to her blouse, the audience burst into cheering.

Not even in her obituary notice was Mrs. William Herbert Trott, one of five sisters and four brothers of the pioneer Kier family of Somenos, identified by her Christian name. Fortunately, it is given on her headstone, here in Mountain View Cemetery. Georgina Kier Trott left no children.

Often the epitaphs are more intriguing than the headstones themselves. Some reveal surviving family members’ unshakeable faith in an Almighty Power. Such as this one that bespeaks a life cut short: “O Mother dear, Weep not for me nor yet be over sad. The fewer years I lived on earth the fewer faults I had. And all the sufferings are now ended, All thy sorrows now are o’er. Thou are soon safely landed on a peaceful, blissful shore.”

For all the grief of losing a loved one, that resigned acceptance of God’s Will often shows. As in the loving remembrance of Lewis Hall, native of Staffordshire, England, who died, aged 55, September 6, 1880: “Call not back the dear departed, Anchored safe where storms are o’er, On the borderland we left them, ‘gon to meet and [?] no more.”

And: “O when the friends We love the best lie in their churchyard bed, we must not cry to[o] bitterly over the happy dead. Because for our dear savior’s sake, our sins ever all forgiven. And Christians only fall asleep to wake again in heaven.”

On a child’s headstone: “Grieve not for us, our dear father. We are not dead, but sleeping here. We are not yours, but God’s alone. He loves us best, and took us home.”

Helen B. Evans, who died July 30, 1915, aged three years: “Of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.” Alan Leslie Bonnington, Aug.2.37. May.24.42, “Love.Liveth.On.” And Ernest Francis (Frankie) Mayea, 1940-1942, is “Safe in the arms of Jesus.”

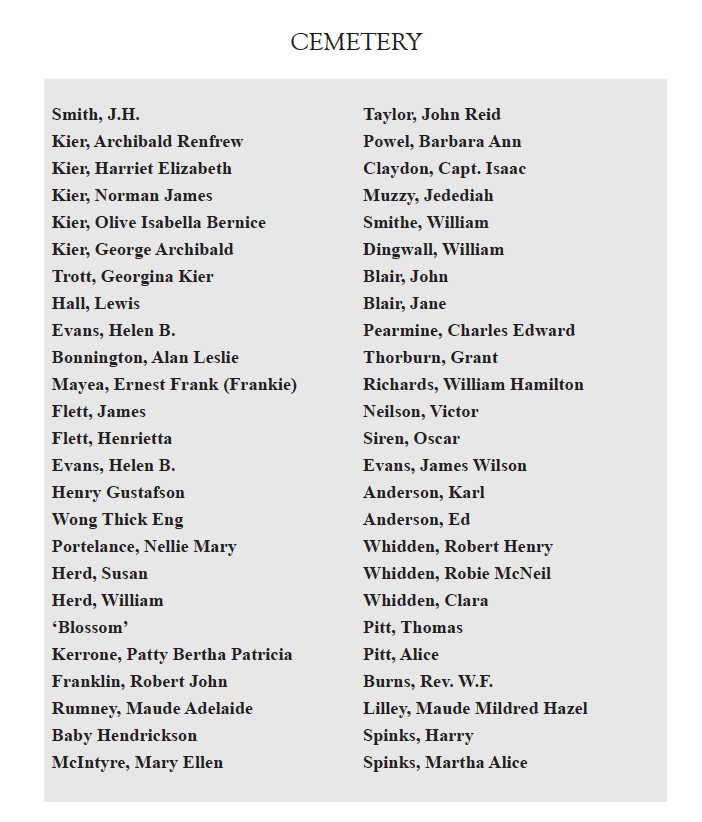

All these are in marked contrast to the terse, “James Flett, Father, 1875-1940; Henrietta Flett, Mother, 1866-1940.” And Henry Gustafson, killed March 1, 1932. The headstone of Wong Thick Eng, June 10, 1946-May 14, 1949, is almost accusatory in its epitaph: “Died King’s Daughters Hospital.”

On a more uplifting note: Nellie Mary Portelance, Jan. 27, 1913-Nov. 9, 1991, is “Remembered as a woman who loved to laugh, Lived life to the fullest with all it’s [sic] joys and sorrows.” And Susan Herd, 1866-1934, William Herd, 1862-1953, enjoys “Everlasting Arms.”

The white marble marker set in concrete for ‘Blossom,’ September 20, 1898-October 4, 1924, almost cries out with its suggestion of William Randolph Hearst’s ‘Rosebud’ in Citizen Kane. Also distinctive, despite their being smaller and less elaborate, are the headstones that mark the Japanese section, many of which, if not most, have been mended after being vandalized. An exception to deliberate damage is that of the grave with an arbutus tree growing up through the centre, displacing both headstone and curbing.

Although members of several pioneer Valley families are interred here, it must be remembered that, originally, this was a Methodist cemetery, meaning that the Old Section is not all-inclusive. You will see headstones for Evanses, Kiers, McLay, Pitt, Castley, Boal, Whidden, Mann, Flett (most of whom are in the Pioneer Cemetery, Maple Bay), Cavin, Grassie and Corfield, to list some prominent Valley families.

In the trees beside Drinkwater Road are 28 graves of Japanese which date back to when this was part of the Somenos Methodist Church. As Mike Biehling, a member of Victoria’s Old Cemetery Society and very serious cemetery researcher reminds us, for these funerals “a portable altar was set up and a short service held, worshippers swept the graves, and carnations were laid on each burial”.

It is most fortunate that Mountain View Cemetery did not suffer the total desecration of its Japanese graves as occurred at Chemainus.

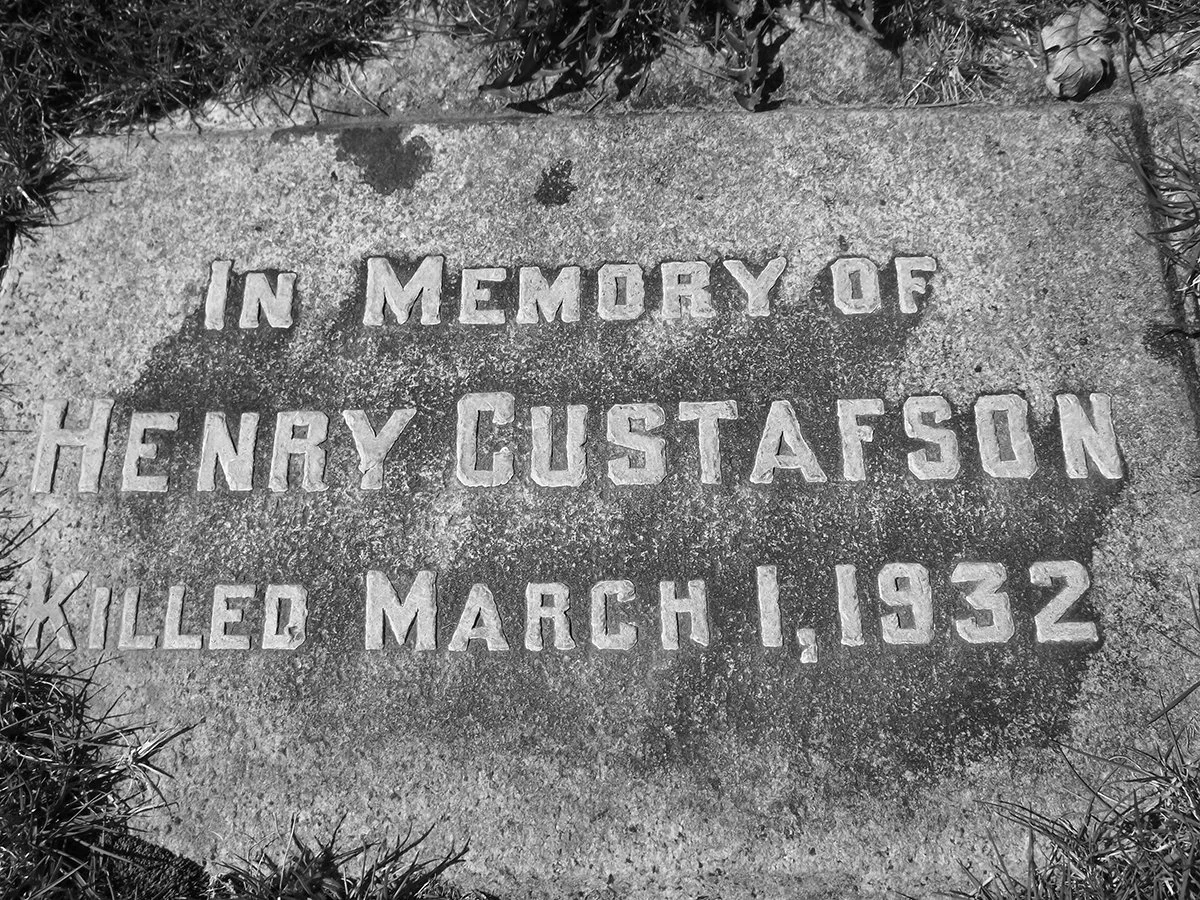

Among the most poignant graves are those in the old Children’s Section which includes a Stillbirths Section. According to Mike’s research, there are as many as 148 burials of stillborn babies “who appear to have been buried in tiny plots just west of the Children’s Section”. Although within the chain link fence it is possible that they encroach upon what now is Somenos Road easement.

Hendrick, son of Charles & Mina. Still born, April 26, 1932.’

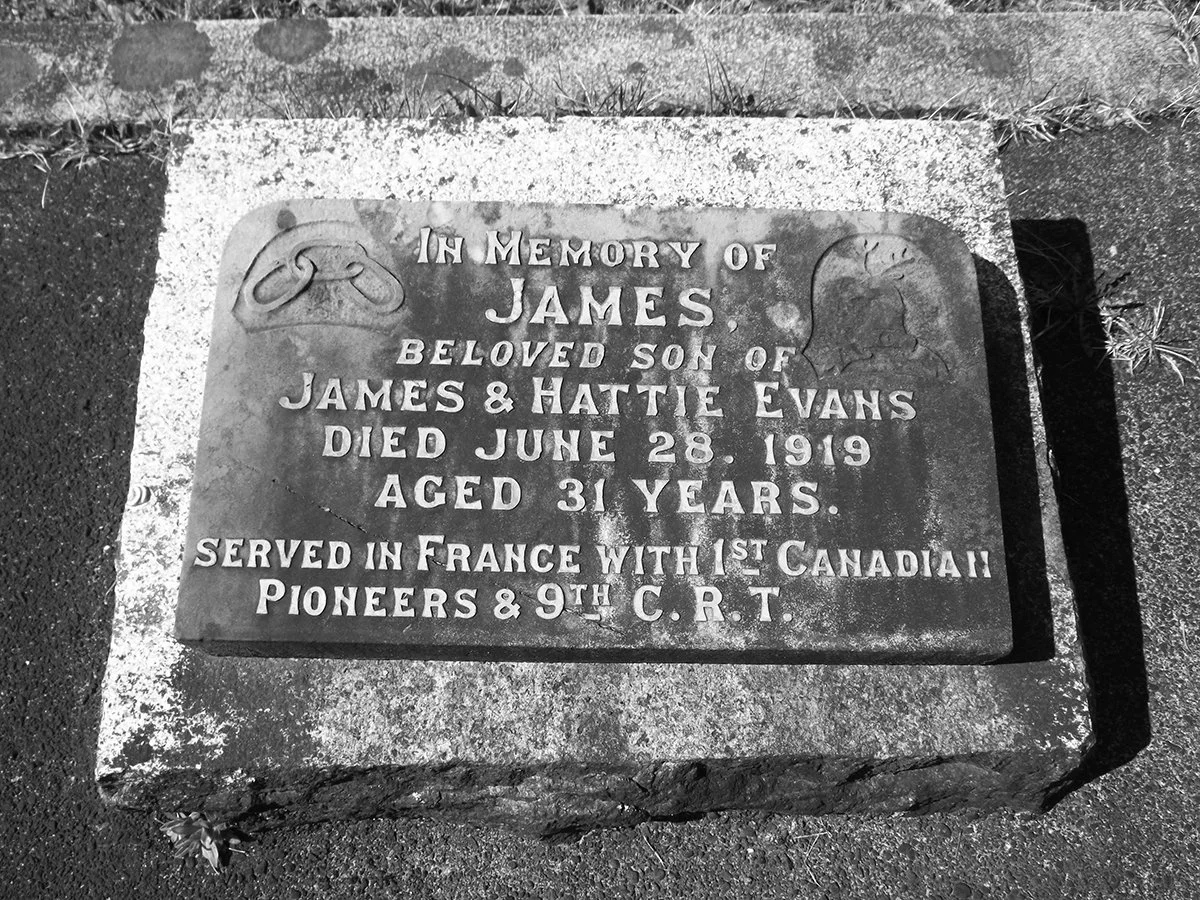

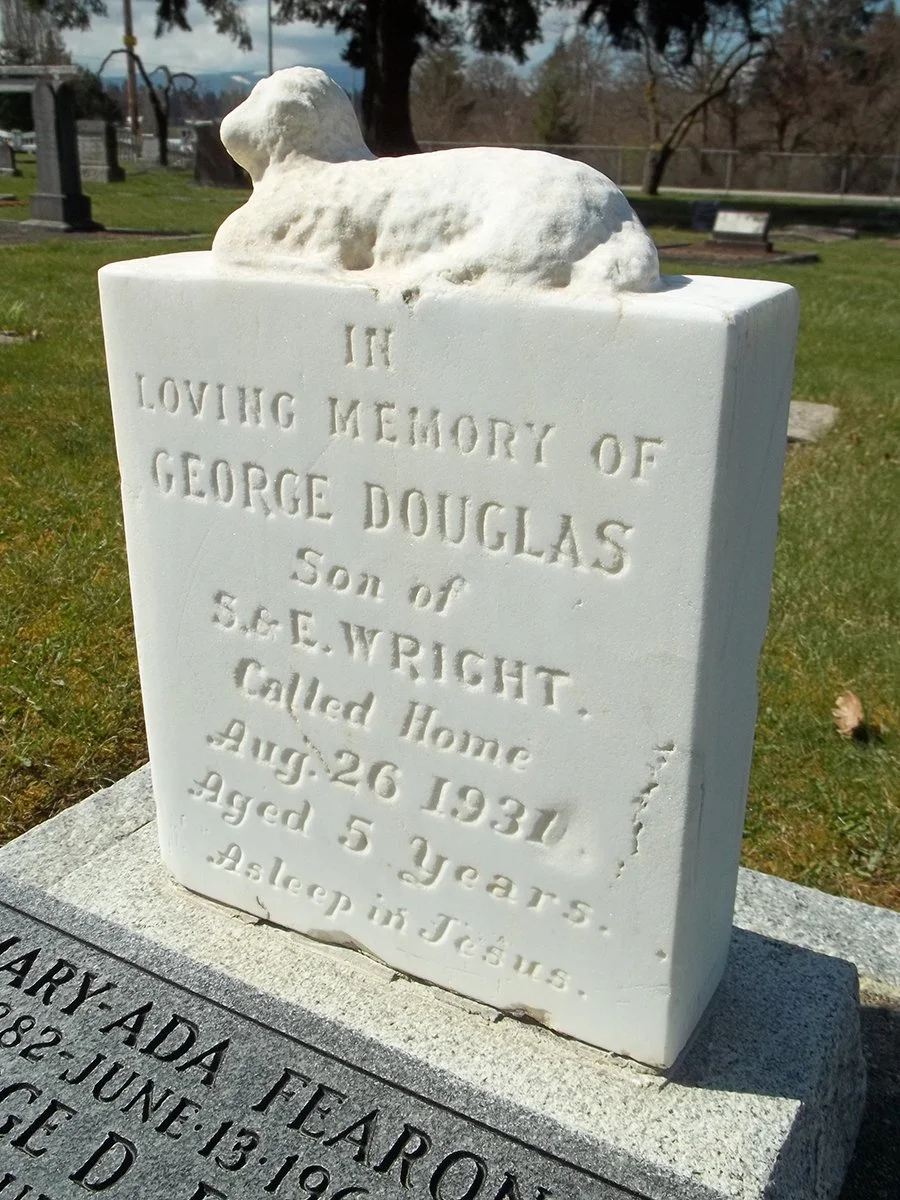

Particularly eye-catching is the sculpted figure of a lamb which is in loving memory of Patty Bertha Patricia Kerrone, daughter of J.&J. Kerrone, who “fell asleep Aug. 2, 1938, aged 2 Yrs. and 10 Mths. God needed one more angel child.” That professed faith in God shows, again, on the grave for Robert John Franklin, “Bob,” who was “called home” Mar. 2, 1919, at the age of three years nine months. “For of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.” And, Maude Adelaide Rumney, January 11, 1904-January 10, 1914, who was “Budded on earth to bloom in Heaven.” Baby Hendrickson, son of Charles and Mina (no surname is given), April 26, 1932 is more succinct: “Stillborn.”

Could “Budded on earth to bloom in Heaven” have been said for Mary Ellen McIntyre, five, of Cowichan Station?

In March 1927 she and her three-year-old sister Florence were playing in the chicken house, their parents just having moved to the farm property the day before. “Goods, therefore, were not properly straightened around and some were in the chicken house where the accident occurred,” reported the Leader. Somehow the girls got into two boxes, one full and one half-full, of dynamite caps. (Although it was not so stated in the news account there is strong inference that they had been left by the previous owner). It was surmised that Mary Ellen dropped one of the boxes, the resulting explosion and the sisters’ screams drawing their mother, an older sister and a neighbour to their side. Both of Mary’s hands were all but severed, she was blinded and disfigured; Florence also suffered severe facial wounds but her eyes were untouched. At the hospital, what was left of Mary’s hands were amputated at the wrist and one eye was removed. Perhaps mercifully, she died that evening.

The centre window in the apse of the Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm Chapel at Cowichan Station honours the memory of John Reid Taylor. He arrived at this farm for British orphans and underprivileged children in November 1936 with his sisters Agnes, Ena and Katherine. John became ill on Good Friday, 1937 and was taken to the Duncan hospital. When his condition worsened it was decided that he should go to Montreal, accompanied by a school nurse, for special treatment. The CPR made this possible, without charge, through one of the school’s patrons. At the Royal Victoria Hospital’s Neurological Institute, McGill University, John was operated on by one of the top neurosurgeons in the world. Although his sight was restored, the malignant brain tumour could not be totally removed and, returned to Fairbridge in June, John died, aged 12, October 27, 1937. His funeral service was held at St. Peter’s, Quamichan but, as you can see, John Taylor is here at Mountain View. Mrs. F.M. McPherson, Victoria, contributed his memorial window at Fairbridge. The graves of John Taylor and several other Fairbridge children, interred where the new and original cemeteries meet, are distinguishable by their identical slanted stones bearing the FFS emblem.

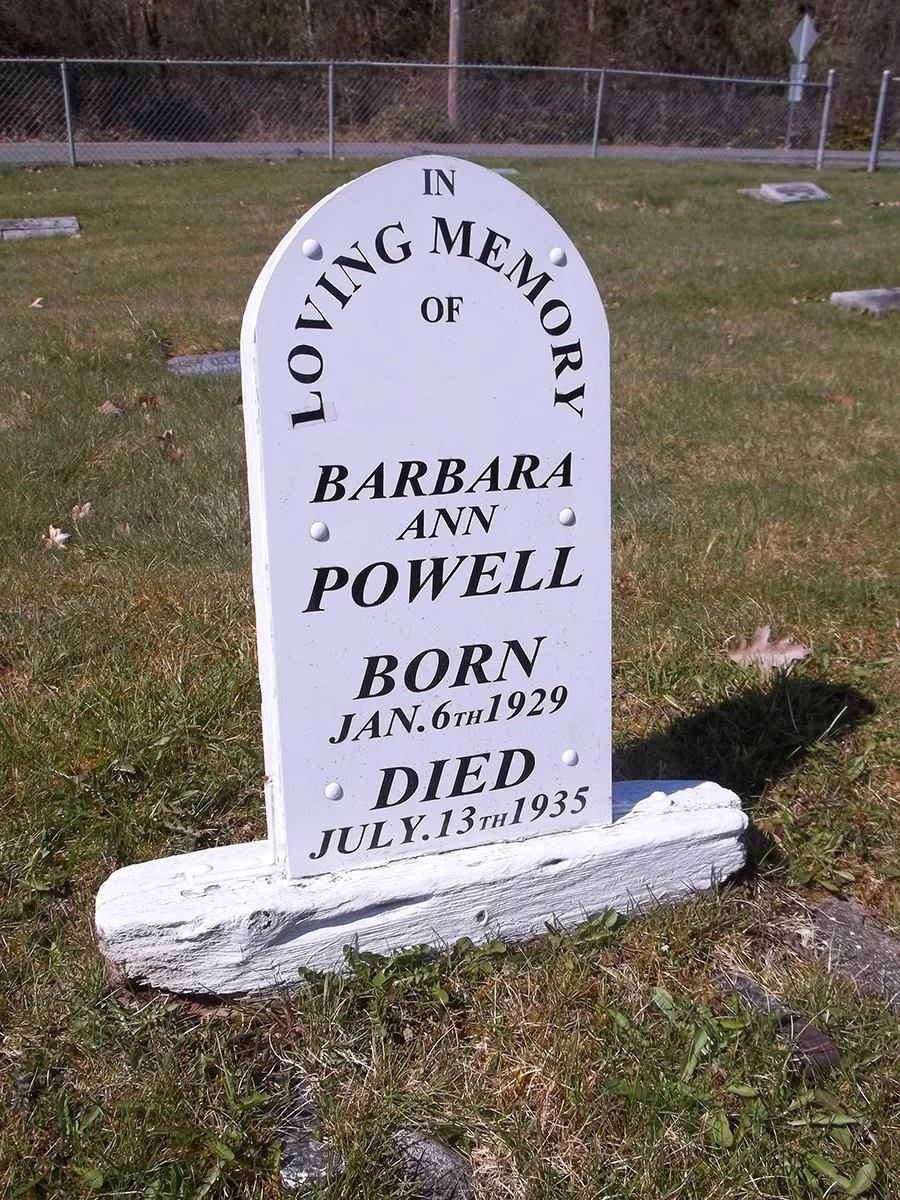

Outstanding for its shape and stark whiteness is the wooden marker for six-year-old Barbara Ann Powell, January 6, 1929- July 13, 1935. It is singular because it is so much like those you would see in a ‘Boot Hill’ of the American West. The black marble headstone of Rev. William Forsyth Burns, 1875-1963, minister of Duncan United Church, 1926-1946, “and a beloved citizen of Duncan,” also stands out among its neighbours. What draws visitors’ attention to the headstone of Capt. Isaac Claydon is the fact that it rarely is visible, being screened from view by a lush patch of Oregon Grape. A retired master mariner upon his death in May 1925, he had been a Cowichan resident for 13 years. He had no known relatives in Canada. Perhaps the most distinctive name in this part of Mountain View Cemetery is that of Jedediah Muzzy, April 21, 1857-April 8, 1935.

Undoubtedly, Mountain View’s most illustrious resident, beneath the red granite column just inside of the cairns, is the Hon. William Smithe who died in office, in 1886, as the sixth premier of British Columbia, 1882-1887. Born June 30, 1842 in Matfen, Northumberland, he came to Canada in 1862 as a 20-year-old and, after trying his luck as a gold miner in the Cariboo, took up farming at Somenos. Because farming, like mining, was precarious, he supplemented his income by serving as Cowichan’s commissioner of roads. “A most agreeable and charming young man as well as a hard-working one,” S.W. Jackson has described him in his book, Portraits of the Premiers, his farm prospered and his public work earned his local status.

A staunch Methodist and teetotaller with a long peppered-black beard that made him look like he had posed for the picture on a box of Smith Brothers cough drops, Smithe then embarked upon a journalistic career. After working in San Francisco as a newspaper reporter for a year and a-half, he returned to the Island and, by this time married to Martha Kier, fourth daughter of G.A. Kier, Esq., again changed course by running in the 1871 provincial election as an independent candidate for Cowichan. After topping the polls, he sat as a non-aligned member of the opposition for five years when he was offered the dual portfolios of finance and agriculture in the A.C. Elliott government. Less than two years later, he was chosen to succeed Elliott as leader of the party which, by this time, was out of office.

When Premier Robert Beaven’s party was obliterated in the polls, Smithe was asked by Lieutenant Governor Cornwall to form a government. William Smithe’s four years as premier (while holding the portfolio of Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works) are noteworthy for their cordiality with the Dominion Government at a time of strained relations arising from unresolved issues related to the terms of Confederation. His government is also remembered for its anti-Chinese legislation although it should be remembered that it was in general accord with the sentiments of most voting British Columbians of the day.

In 1886 the Smithe government was returned to office with a comfortable majority. But it quickly became apparent that he was seriously ill–he had been for over a year–and he left Victoria to convalesce on his brother’s farm at Somenos. Three months later, he died in a private home in Victoria, within a block of the provincial legislature buildings, the famous Birdcages. Or he, as the Nanaimo Free Press put it in purplish prose, “passed quietly into that world which lies beyond this mundane sphere”. He was 45.

British Columbia Premier William Smithe.

Given a state funeral in Victoria, Smithe’s body was returned to Somenos aboard a special E&N train carrying his family and relatives, members of the legislature and senior civil servants. “On the arrival at Somenos, a large concourse of the settlers was present to pay the last sad token of respect to one who had lived and laboured in their midst, and whom they honoured and esteemed for his many virtues and upright manly qualities.”

Poor William Dingwall landed on his shoulder when he was thrown from his wagon in March 1914. While driving along Front Street (today’s Canada Avenue) in Duncan, two railcars bumping together spooked his young horse into a gallop. “The animal went at such a pace that it could not make the turn at the Anglican church and it therefore stopped dead when it neared the fence, throwing Mr. Dingwall out of the rig. He landed on his right shoulder on the bank on the side of the road, then bounced up to the fence about eight feet away. Dr. Dykes was summoned and Dingwall was taken to the hospital. He was conscious almost up to the time of his passing away at 1 p.m. Friday [23 hours after the accident], death being due to internal injuries.” Dingwall, 52, was road foreman for North Cowichan Municipality; from Dingwall, Scotland, he is remembered by Dingwall Street. He was unmarried.

John Blair of Sahtlam, landscape gardener, is how he was described in his obituary, it being noted that the “large number of floral offerings were a fitting tribute to one who had loved and labored among them so long”. He had indeed made landscape design his life’s work after migrating to Canada from Scotland in 1851. Among his achievements were Chicago’s Garfield, Humboldt, Douglas, Lincoln and Jefferson parks and, after coming to the Island in 1882, Victoria’s Beacon Hill Park. What made his creations stand out from the traditional European style of parks, according to his biographer the late Bill Dale, was his incorporation of “more natural settings using trees, rocks and water”. Said the Chicago Evening Journal of one of Blair’s private commissions, “One is struck with the perfect taste displayed in all the combination of variety with unity and simplicity, which is everywhere seen in nature and so rarely seen in the workings of man… What a blessing to any State is the presence of such a man, surrounding our homes with scenes of beauty, which silently educate us into the love of the true, the beautiful and the good, and even exert a powerful influence in winning the poor, the dissipated and the depraved to a higher and purer life.”

Blair, who said he took much of his inspiration from the poets, helped lay out the town of Colorado Springs, Colorado, its richest estates and its Evergreen Cemetery. In San Francisco to meet with Luther Burbank, he heard of the rich stands of forest on Vancouver Island and came north to see for himself. He found what he was looking for at Sahtlam, four miles west of Duncan, and with the help of his son John cleared enough land to build a cabin and plant a garden, fruit trees and the first of dozens of exotic trees, many of which survive to this day. Blair was 62 years old when he began this work in 1882. Six years later, he submitted the winning proposal for the design and building of Beacon Hill Park. In 1889, with the able assistance of parks foreman and fellow Scotsman George Fraser, he began with the creation of Goodacre Lake from what had been swamp. More than a century and a quarter later, “the basic layout envisioned by John Blair is still there centered around his famous stone bridge”. John Blair died May 28, 1906; Jane Blair, nee Jane Black of Ayershire at Doune Perthshire, followed him, March 8, 1921. They left three daughters and one son.

Charles Edward Pearmine also worked with the soil, so to speak. But, not to grow things. Rather, he set out to dig a coal mine. At Somenos, beside the E&N Railway grade, of all places. He had no reason whatever to think he would strike coal there, it was just something to do. At the time he was interviewed by a Victoria newspaper reporter, in 1931, he was all of 85–and still digging. He had apprenticed in his father’s shipyard in the Old Country, he said, which filled him with a sense of wanderlust. He sailed from London when he was 23, the time of the Crimean War, and made good money “trad[ing] with buffalo hunters in Texas” before making his way, for reasons unstated, to Vancouver Island and eventually settling at Tyee (Stratford) Crossing, Somenos, in a cabin just eight feet by 12 feet. Since the completion of the railway in 1886, he had met “practically every train,” acting as unofficial station agent and postmaster. “I merely do it as a kindness to my neighbours,” he explained.

He was a bachelor by choice, he said, not for lack of offers from the opposite sex. But he was more interested in his coal mine. For three years he had been picking away and was down about 50 feet even though he did not own the mineral rights to his claim. “If I should find coal it will increase the value of the land, so this is the next crop I am interested in, something underneath the ground where the deer cannot eat it.” The fact that his shaft had half-filled with water did not discourage him, either, he just went on bailing, picking and shovelling. “I work in the daytime and use the sun when it is overhead for my lamp. By and by, I hope to have a miner’s lamp on my head when I go down.” It mattered not that he failed to strike coal, he intended to dig ‘til he dropped. His interviewer had to admit that he appeared to be hale and hearty and did not look his age.

Between diggings he met the trains, sorted the mail, guarded the freight and greeted the occasional passenger, all as a public service. “You can put me down as an optimist, at 85. I may not get any money for what I am doing, but if I were a young man again I could make all kinds of money with the knowledge I have of the world. I missed all kinds of chances and can see them now for others.”

In November 1930 the “adventurous wanderings of the late Grant Thorburn came to and end...in Mountain View Cemetery, Somenos, where he was laid to rest after a funeral service in St. Andrew’s Church, Duncan.” So reported the Colonist of the proprietor of the Tzouhalem Hotel, Duncan. Thorburn, in the words of the Rev. R.M. Rollo was “one of that fast-dwindling band of true pioneers who have done so much to build up the present prosperity of our Dominion”. Born in Nova Scotia, he sailed before the mast on a clipper ship when he was only 16. In due course he became “the first white settler in the Qu’Appelle Valley, [a] member of the Canadian Pacific Railway surveying party in the Rockies, a fighter with the Moose Mountain Scouts in the Riel Rebellion, a mail carrier on the long route from Qu’Appelle to Edmonton, and a sharer in the early days of every successful mining camp in British Columbia and the Yukon”. This is an impressive resume by anyone’s standards. Thorburn, 74, known for his generous and friendly nature that had earned him a legion of friends from the Red River to the Yukon, left a wife and two daughters.

There are almost 300 names of the military casualties of two world wars and Korea on the Duncan Cenotaph; one has to wonder how many Cowichan loggers have been killed in the woods over the past 150 years since the arrival of Europeans. We know of many of them from newspaper reports. But Duncan did not have its own newspaper until just after the turn of the last century and no one, to the author’s knowledge, has attempted to compile an accurate tally. Perhaps the youngest forest fatality at Mountain View Cemetery is William Hamilton Richards, July 18, 1931-April 29, 1947, killed by a falling log at Rounds, in the Gordon River area. He was just 15 and five weeks on the job. Twenty years before, in late February 1927, Victor Neilson, a young Dane, was struck by a falling snag while working as a chokerman for the Elco Logging Co. at Lake Cowichan. Neilson, 25, had been in Canada only three years.

Three months later, another Elco Co. employee was fatally injured when struck from on high, this time by the spar tree when it collapsed because of a broken guy wire.

Oscar Siren, a 45-year-old Finlander, was helping to load a log car when he was struck. He had been in Canada for 15 years and had developed many friendships as evidenced by the turnout and the floral arrangements at his funeral, many attending from the Ladysmith area.

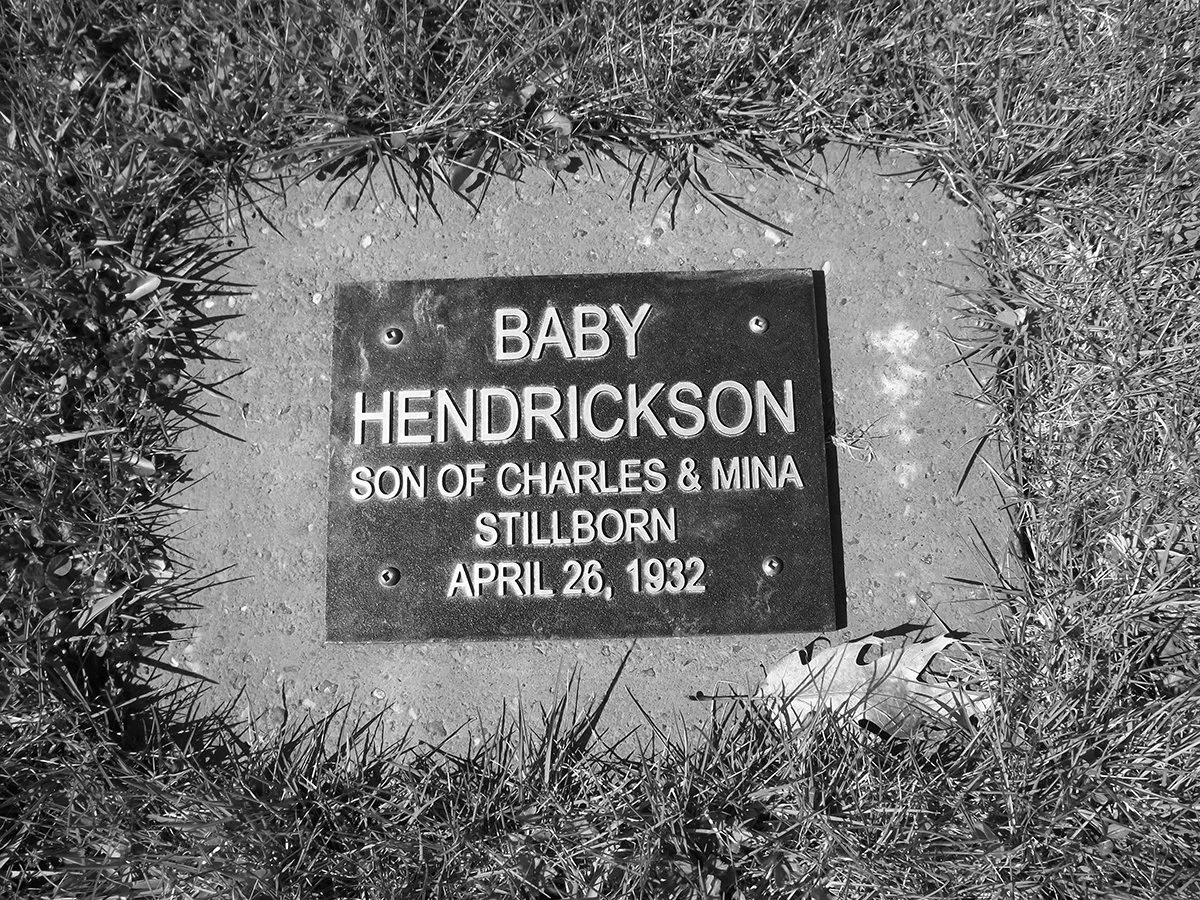

James Wilson Evans, “beloved son of James and Hattie Evans,” had suffered a similar fate eight years earlier. The eldest son of the pioneering James Evans family was 31 years old at the time of his death, June 28, 1919. Which is as much as you will learn from his headstone. It was his youth and family connection that sent me into the 90-year-old newspapers via microfilm. Had Evans, I wondered, died belatedly of injuries suffered during the war?

No, as it turned out. Just 10 weeks returned from two and a-half years in France with the 1st Canadian Pioneers, he was killed on Hill 60 on a Thursday afternoon while he and E.W. Latter were working for P. Auchinachie who had a contract to build a road to the new manganese mines. When they dropped a large fir, it lodged between two snags. As Evans stepped out from his shelter behind a tree, one of the snags snapped, halfway up. It was this ‘widow maker’ that lived up to its dreaded name by striking him on the head.

The grave of James Evans who survived the horrors of the First World War to be killed in a logging accident within weeks of coming home.

He was hauled two and-half miles down the mountain on an improvised stretcher to the Cowichan Lake Road where Dr. Dykes and an ambulance were waiting. He underwent surgery at the Duncan hospital but died at 4 o’clock next morning without regaining consciousness.

His funeral at the Methodist burying ground, Somenos was well attended, the service being officiated by J.W. Dickinson for the I.O.O.F. His cousins, Robert, William, George, John, James and Newall Evans, acted as pallbearers.

You sense none of this drama from James Evans’s headstone: “In memory of James, beloved son of James and Hattie Evans. Died June 28, 1919, aged 31 years. Served in France with 1st Canadian Pioneers & 9th C.R.T.”

James Evans was a civilian when he died but, as noted, his headstone cites his wartime service. He is not the only veteran at Mountain View, of course, but a less visible military presence prevails here than at some other Valley cemeteries. Researcher Mike Bieling commented on this curious fact some years ago: “Instead of the markers detailing rank and pride of membership in the British military tradition, these stones tell us that a different social stratum lies buried here. These people were among the Valley’s true pioneer stock, mainly from the lower classes and from Low Church backgrounds, many Welsh and Scots, who arrived with meagre resources and little support from the Old Country, and labouriously carved farms out of the wilderness. We thought it significant that only 10 grave markers in the entire Old Section offer any record of an individual’s military service, and that of these, only two predate 1949. Veterans’ burials in the Municipality’s New Section, and in the Royal Canadian Legion Branch No. 53 Veterans’ Section, are more reflective of the high levels of participation of young Canadians in the military in World Wars I and II.” (Mountain View’s veterans’ graves have been dealt with in greater detail in the chapter, ‘Remembering Our Veterans.’)

You do not learn much from the Anderson headstones. According to the news reports of their deaths, there is no blood relationship between Karl Anderson, drowned July 16, 1933 and Ed Anderson, killed March 10, 1934. However, the fact that they lie side by side in Mountain View Cemetery poses something of a mystery respecting these two men who died within eight months of each other. At the very least, it is an intriguing coincidence. Both were loggers. Both worked at the same camp. Both have identical headstones of granite. Both names are misspelled.

The common agency behind their burials was the R.H. Whidden funeral parlour. But the headstones are expensive for two “paupers” to have been paid for from the public purse. Were they purchased by their workmates or their employers? Again, there is the matter of expense as 1933-34 was the very depth of the Great Depression.

Anyway, let us start with Karl. The July 20th 1933 Cowichan Leader’s front page headline reads, “Drowns off boat while companion clings to its upturned keel.” Carl Anderson, as he is identified, also known as “Snoose Charlie,” was a 43-year-old Cowichan Lake logger of Swedish birth. Some time after 5 o’clock Sunday afternoon, July 16th, after spending the weekend in Lake Cowichan, he and Waino Murray (originally identified as W. Nummo) returned to the Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing Co.’s Camp 10 on the South Shore, having hired a local man to row them the half-mile across the lake. For some reason, they changed their minds, launched a small boat kept at the camp and headed back down the lake despite the fact that a brisk wind was blowing and creating a heavy chop.

First indication that they were in trouble came from young Harvey Carnell who heard cries for help from the vicinity of the Lakeside Hotel on the North Shore. He quickly alerted W.H. Atkins, the hotel’s manager who had water-taxied the loggers earlier. Atkins, despite the wind-whipped waters, quickly rowed alongside the overturned boat. He found Murray clinging to its keel but there was no sign of Anderson who was a non-swimmer.

A faller, he had lived at the lake for several years and was well acquainted. His only relative was thought to be a sister, a nurse at Victoria’s Royal Jubilee Hospital, who was visiting in Sweden at the time.

Now to Ed Anderson whose headstone informs us that he was killed March 10, 1934. He is identified in the newspaper as being 47 years old (he was 44) and of Norwegian not Swedish birth like Karl. He, too, worked as a logger at Camp 10. At the time of his death he had resided in the area for at least six years. Although he also died on a weekend, he was at work when he was struck by a turn of logs as it was being hauled in by a donkey engine. As the logs were hoisted along, just above the ground, they caught on a snag and the load suddenly veered towards him.

At the coroner’s inquest Anderson’s workmates said they thought he saw the air-borne mass racing towards him at 600 feet per minute, but he could not duck in time. Whistleman Earle Johnson, who saw what was happening, signalled the donkey operator to stop the engine but this could not be done in time. Other witnesses to the accident included Carl Carlson, chokerman, and Angus Nolan, his rigging-slinger, who deposed that he thought the victim’s choice of position vis a vis the turn’s intended line of travel to have been a poor one.

Held in the Whidden funeral parlours, a coroner’s jury, Dr. H.P. Swan presiding, ruled accidental death, as had a jury in the case of Karl Anderson months earlier. The actual medical cause was said to be a fractured skull and hemorrhage. Single, his family in Norway, Ed Anderson had been popular with his fellow loggers and “a great favourite with the children at the lake who have reason to remember his generosity. True to his type, he was a hard worker and a good spender...his big frame and handsome features making him an outstanding figure”.

Camp 10 closed for a day so that Anderson’s friends and co-workers could attend his funeral and burial service in Mountain View Cemetery. Which is where he is today, immediately beside Somenos Road and immediately beside Karl Anderson. Anyone viewing their identical granite headstones likely assumes that they are brothers. As shown, this is not the case. But who paid for their grave markers? As it happens, whoever did, got their names wrong: Karl should be Carl and both men were Andersen with an ‘e’.

Another example of a lamb head stone for a child, this one for George Douglas, son of S. & E. Wright, called home August 26, 1930, aged 5 years. Asleep in Jesus.

Shades of Boot Hill: the stark white marker for Barbara Ann Powell.

This photo captures the sharp detail of George Linton Buckham’s red granite head stone. Many other markers of lesser quality are wearing away, some to the point of being illegible.

Some of those who played peripheral roles in the Andersens’ tragedies are also here at Mountain View. Of Empire Loyalist stock, originally a wheelwright and carpenter, mortician Robert Henry Whidden had begun making coffins as a sideline then opened his own mortuary in Duncan. Born at New Annan, Nova Scotia, November 2, 1857 he died September 6, 1940, aged 82 years, after a long career that included an active role in civic affairs. The first Methodist service held in Duncan was held in the Whidden home. He served on Duncan and North Cowichan councils, was captain and honorary life member of the city’s volunteer fire brigade, a charter member of the Maple Lodge, Knights of Pythias, a Rotarian and a member of the Loyal Orange Order. Mrs. Whidden, Robie McNeil Whidden, July 10, 1859-July 30, 1933, also from Nova Scotia, predeceased him and their two daughters and a son. Whidden, who had overseen hundreds of burials, no doubt would have been pleased by his own funeral service, which was well attended with “many floral tokens of esteem”. A “most estimable citizen,” Mrs. Whidden was the fourth white woman to take up residence in the Duncan of 21 souls in 1889. A devoted churchgoer, she, like her husband, was active in the community and had worked alongside him in the mortuary. Also here is unmarried daughter Clara Whidden, 1885-1973.

Both coroner’s juryman Thomas Pitt, 1870-1938, and United Church minister, the Rev.William Forsyth Burns, 1875-1963, have distinctive headstones. (It was Burns who planted the Japanese plum trees which adorn the cemetery today, sometimes carrying water all the way from town.) The Burns headstone is a large rectangle of obsidian-black, that of Thomas and Alice Pitt, 1877-1952, has an open book on top. Born in Worcestershire, England, Pitt emigrated to Duncan when he was 20 to begin a successful career as a merchant after several years as a manager of the Alderlea Hotel. With A. Peterson he bought out Harry Smith’s Emporium and ultimately merged with W.P. Jaynes as Cowichan Merchants, Ltd. Their downtown store, which underwent a complete restoration in recent years, is a Duncan landmark.

Rarely have Cowichan police faced such a gruesome mystery as that which began with the discovery of a dislodged board, a mile south of Crofton, in the volatile summer of 1933. That was a hot and dry year with logging crews and provincial forestry officers kept busy chasing about the Valley as they sought to contain scattered bush fires.

Fire was not a concern for sheep farmer Charles Ecclestone; he had other priorities. He had leased a derelict farm from the Welshes and it was all he could do to look after his flock and attend to the never-ending chores that went with one-man farming. When he noticed that a 2x12 plank atop an old well was out of place, he thought it odd and dangerous, no doubt about it, but he had enough to do without worrying about why anyone would move it. So he just replaced the board and dismissed it from mind. By the time police became involved, in early September, he could not even remember just when he had done so; perhaps five weeks before?

It was not until he moved his flock from an adjoining field that he returned to the well. This time, intending to utilise it for his sheep, he removed all the planks. That’s when he noticed that the water, within 15 inches of the surface, had a “slightly muddy colour.” And it smelled. Probably the work of rats, he grumbled to himself.

But there appeared to be something in the well and, cupping his hand over his nose and mouth, he leaned forward and peered into the depths. It looked like clothing.

That was when he called Provincial Police Const. A. Donahue at Chemainus, who notified the Duncan detachment, who passed word onto Victoria. Donahue was waiting for Cpl. A.D.I. Mustart and Const. S. Service when they reached the old homestead at 10 o’clock the next morning. Within short order they had recovered the decomposed body of a woman. Attached to her left wrist by a piece of picture wire was a valise, containing personal belongings. Around her neck there appeared to be a large bluish bruise. The corpse was beyond recognition but a wristwatch, stopped at 1:40, and a small mantel clock, stopped at 12:31, made for promising clues.

A painstaking search of the abandoned farmhouse, outbuildings and ground for a quarter- mile radius of the well, yielded nothing of interest but some writing on the bedroom walls which was not thought to have any connection with the case. The well, 13 feet deep, was pumped out but no further clues were found.

As the valise contained only clothing, toiletry items and a travel iron besides the clock, Constables Donahue and Service focussed their attention on the items in the woman’s purse. There was no ID, just $26.06, a key and two ticket stubs. Although it is not explained how in the news accounts, they were able to trace a key to her former place of employment and even found the shop that repaired both watch and clock.

Thelma Lilley of Victoria confirmed that these items belonged to her sister, Mildred Maude Lilley, 29, who had left their Fort Street home July 13th to seek work in Vancouver. She had caught the midnight CPR boat and ticket stubs in her purse confirmed that she had taken the night boat to Vancouver and returned to the Island via Nanaimo on the 17th. She arrived in Duncan the following day.

That was six weeks before. About the length of time the body had been in the well, according to medical evidence. Perhaps most telling was the finding of wire in Miss Lilley’s rooms in Victoria that appeared to match that which bound the valise to her left wrist. This strongly suggested suicide and premeditation.

In Duncan, police inquiries turned up taxi driver Ernie Sedola who remembered driving a young woman from the Tzouhalem Hotel to the Crofton farm, in the evening of the 19th. He dropped her off about 8 o’clock. A check of the hotel’s register showed that ‘E. Brown, Vancouver,’ had stayed for two days.

This set the stage for a coroner’s jury at R.H. Whidden’s funeral parlour. On the witness stand Thelma Lilley testified that her sister, who had lost her job as an elevator operator at the Pemberton Building in December because of her “abrupt manner,” had “seemed strange” in the months before she left home for, as far as the family knew, Vancouver. Her “most unusual manner” was also noted by Miss Theresa Thorburn, daughter of the proprietors of the Tzouhalem.

By this time there was no doubt that Maude Lilley and E. Brown were one and the same. Her clothing, a black hat, black kid gloves and black winter coat worn over black clothing with brown silk stockings and brown high heels, had been identified as that of the strange guest by a hotel employee. According to the register, she had checked in at 9:30 a.m. on Tuesday, July 18th, and checked out the following evening at 7:30. During those 34 hours she had never left her room nor ordered anything to eat. So concerned did Mrs. Thorburn become by the prolonged silence in her room that, the second day, she knocked on the door. Receiving no answer, she went to a balcony that overlooked the woman’s room. From that vantage point, she could see her sitting on the edge of the bed as if she were about to get dressed.

Mrs. Thorburn again rapped on her door. This time the strange guest admitted that she had heard her before but did not wish to be disturbed. Later, at the inquest, Mrs. Thorburn would recall ‘Miss Brown’s’ dishevelled appearance. She thought her to have been “much painted up” and on the verge of exhaustion, with a “haggard, forlorn look”. Miss Brown said she had not slept for some time but Mr. Thorburn thought there was more that was “queer” about her than lack of sleep.

Part of the mystery that surrounds Maud Lilley’s tragic death is the fact that, despite her subdued behaviour at home in the months preceding her going to Vancouver, neither father nor sister had become sufficiently alarmed by her prolonged absence to make inquiries or to get in touch with police. This, despite Maude having promised to write within a week and, failing that, come home. They said they had been expecting to hear from her any day.

A rooming house keeper who admitted that his wife was in a mental hospital, Walter George Lilley said there was no animosity between him and his daughter or between her and her two sisters. She had appeared to be her usual self when she left the house where she lived in her own rented suite. He said that he “considered her to be of too studious a nature to be melancholy. She was a deep thinker [who] always spoke common sense”. She had few friends, none of them male.

Thelma Lilley had noticed subtle changes in Maude, in particular that she no longer wanted to socialise outside the family after losing her job. Prior to her disappearance she had never been away from home for more than a week, but for two years she had spent with an aunt in the United States when she was in her late teens. That was when the family moved from Crofton, where the Lilleys had homesteaded for almost half a century, to Victoria.

Her father had not been able to identify her remains except for the colour of her hair, but he did recognise her toilet set. Thelma Lilley identified her sister’s clothes, valise and purse. Both of them were adamant that Maude was in “wonderful” health when they last saw her.

The ‘bruise’ around her neck having proved to be dye from her clothing, and there being no other signs of physical injury, police were by this time working on the premise of suicide. The pathologist, instructed to examine her organs for evidence of poison, found traces of a popular sleeping draught but only a tenth of what would be necessary to induce coma and death.

Of particular interest was the revelation that Maude well knew the old family farm where her body was found–she was born and raised there until the family moved to Victoria.

Dr. H.P. Swan, Coroner, instructed the jury to consider death by homicide, suicide or accident. There was no evidence of homicide, he said, and accidental death seemed unlikely because the suitcase had been wired to her wrist and the dislodged plank atop the well had been replaced by Mr. Ecclestone, the sheepherder who found her body. (The implication being that a murderer would have replaced the board, and a suicide, or the victim of an accident, could not.)

The jury needed just 10 minutes to rule, “Miss Mildred Maude Lilley” died by drowning as the result of her taking her own life while temporarily insane.

For reasons that we cannot comprehend, the distraught woman had returned to the farm where she had been born and spent her first 20 years.

The concrete marker for Mildred Hazel Lilley, March 16, 1904-September 8, 1933 (sic). Her tragic death made newspaper headlines in 1933.

This head stone in the Japanese section is being uprooted by this arbutus tree.

The head stone for Harry Spinks, Duncan’s hapless street sweeper.

Martha Alice Spinks, wife of Harry, is with him still.

Perhaps those years of childhood and young womanhood had been the good years, the best years, of her life. Perhaps that is why the family interred her in Mountain View Cemetery so that she would remain in the Cowichan Valley. Maude Mildred Hazel Lilley’s concrete headstone and slab is quite visible just inside the fence on Somenos Road.

Officially, her date of death is registered as July 17, 1933. This, of course, is incorrect as that was the day of her arrival in Duncan, two days before she had a taxi drive her out to the old farmstead and thus at least two days before her death. But it is a lot closer to the mark than that on her headstone, March 16, 1904-September 8, 1933. The latter date is not even that on which her body was found.

Coincidentally, hers was the second death by drowning in a well that year. In April, a corner’s jury had ruled that a prominent Duncan businessman had fallen into his well after stunning himself by banging his head on an overhanging water tank. He was known to have been experiencing money difficulties and the late Jack Fleetwood, Valley historian par excellence, said that it was common belief that the man had taken his own life. As his death was reported to be accidental, there is nothing to suggest that Maude Lilley in Victoria, even if she had heard of his fate, chose to follow his example.

This was not the first time the Lilley family was linked to tragedy at Crofton. In 1884, George Alfred Lilley bought 100 acres on the site of the future smelter town. On Valentine’s Day, 1886, he dropped by his neighbour, Charles Miller, with mail, to find Miller and another neighbour, Henry Dring, had been brutally murdered. Their tombstone at St. Peter’s, Quamichan bears the intriguing inscription, ‘Massacred,’ and their story is told in that chapter.

“Mystery attaches to disappearance of Harry Spinks.” Even back in June 1946, this was an antiquated way of headlining a man’s disappearance. That was when longtime City of Duncan employee Harry Spinks vanished. What makes this story particularly intriguing is that Spinks, the city’s “one-man street cleaning department,” was 83 years old! Not only that, but he had made it known that he wanted to work two more years before taking his retirement!

He apparently left his home on Alderlea Street in the early hours of Tuesday morning, the 25th. At 1:45 a.m. he was seen walking along Queens Road near the V.I. Coach Lines repair shop, headed west towards downtown. But he never made it to work and it was not until five hours later that Mrs. Spinks arose to find that he had left the house without lighting the kitchen stove nor making himself a breakfast as per usual. When she phoned his boss, city works foreman A.J. Castle told her that Harry had not reported for work. It was Castle who, after making several unsuccessful queries, informed police.

Working on the possibility that Spinks was suffering from amnesia, they issued a bulletin to other police departments and had the missing man’s description broadcast over a popular Vancouver radio station. As the hours passed, the fear that he had injured himself prompted parties of police, friends, city employees and volunteers to scour the banks of the Cowichan River, the shores of Somenos Lake and points between, some of them in boats provided by A.A. Sherman of the Dominion Fisheries Office. To comfort her mother, a married daughter arrived from Vancouver.

“No reason for the disappearance of Mr. Spinks can be ascertained,” it was reported. “Despite his advanced years he appeared to be in good health, was of an exceedingly cheerful disposition and was intensely interested in his work for the city and his garden at home.”

By late Wednesday, the official surmise was that Spinks had suffered a sudden seizure, fallen and injured himself, and “his body may be lying in some spot quite close to the city which has been overlooked in previous searches”. The city posted a reward, which was supplemented by his family, for information leading to his whereabouts.

Not until Sunday did searchers find their first clue. It was not a promising one, his hat having been recovered from the Cowichan River near the E.&N. bridge. Consequently, under the direction of Provincial Police Const. J.A. Henry, searchers concentrated their efforts on the log debris that littered the lower reaches of the river. Const. Henry had already more or less ruled out misadventure by the fact that no sign of Spinks had been found within the city limits.

When a plan to dynamite the log jams had to be abandoned because of the Cowichan’s high level because of spring run-off, plans were made to use bulldozers where possible in hopes of finding the body of the street cleaner who was “known to practically every citizen of the district”. So concerned were Valley residents that the Cowichan Leader was flooded with phone calls from those asking if there were any new developments in the case.

Further evidence that Mr. Spinks had met his death in the Cowichan River came with the discovery by 13-year-old Don Douglas of a knee-length rubber boot. Police then found a second boot; both were positively identified as having belonged to Spinks. This renewed interest in the log jams and the city’s street crew went to work with a bulldozer. By this time the reward for his being found, alive or dead, had reached the odd sum of $94.25.

Almost a full month after he left his home without word to his wife, Spinks’ body was recovered a quarter of a mile below the E&N bridge and formally identified by a ring and a flannel belt. At the coroner’s inquest the chief witness was Mrs. Spinks who said she had last seen her husband on the evening of June 24th, that he had not seemed despondent but “very tired” and “somewhat upset” by the previous day’s earthquake. On the morning of the 25th, he had not brought her her morning cup of tea as was his usual practice and when she arose she found that he had left the house. Although his departure was earlier than usual, she was not alarmed as he often started work earlier if he had other duties besides street cleaning. Only when he failed to return for lunch at noon did she phone foreman Castle who in turn phoned police.

Her husband, said Mrs. Spinks, had enjoyed “exceptionally good health” and was of a jovial disposition. Her life with him had been “a happy one. Ours was a happy home. He loved life too much to want to go away. He loved his home and his garden.” She thought it possible that he fell into the river while en route to the city dump on Eagle Heights, a surmise based upon his having been in the habit of wearing his gumboots to work only when he attended to fires at the dump.

Dr. George More, who had performed the autopsy, stated that although decomposition was well advanced, he found no signs of violence and believed death to have been by drowning. The jury concurred as to the cause of death with an open verdict of “found dead”.

London-born in 1865, Harry Spinks came to Canada and Cowichan in 1921 and had worked for the city for 11 years as its only street cleaner, a job where his “happy nature and ready wit made him popular with practically all residents of Duncan and the surrounding district[s].” Although the possibility existed that he had stumbled into the river while on his way to Eagle Heights, it is also possible that he took his own life in a moment of despondency as he had been “considerably worried over negotiations connected with his application for an old-age pension”.

Meaning that his 25 years’ employment as a Canadian hadn’t fully qualified him for OAP. Already 83 years old, he had to work another two years before he could “devote his time to his hobby, gardening”. If he got the OAP. So it was, in 1946.

Harry Spinks, 1865-1946, is “at rest” beside his “rock of ages,” Martha Alice Spinks, 1878-1953. Side by side in the fourth row left (west) of the Drinkwater Road access lane, they left two sons and four daughters.

Note: A listing of Mountain View Cemetery burials prior to 1983 is available online.