The Black and White World of Youbou Photographer Wilmer H. Gold

I’ve always been a tree-hugger and have long been critical of the way forestry has been and is practised in British Columbia. But I’m also fascinated by logging history, and I make no apology for that, either.

A donkey engine crew poses for freelance photographer Wilmer Gold. Are they all short or is that one tall dog?—www.knowledge.ca

As is apparent in his many photos of the men and machinery of the last days of steam railroading and the beginning of truck logging on Vancouver Island, Wilmer Hazelwood Gold had this same fascination.

While I’ve devoted my career to trying to preserve history with the written word, Wilmer Gold’s ‘pen’ was his large-format camera. By large-format I mean saucer and plate-sized negatives that allow the resulting photos to be enlarged almost to mural-size without visible grain.

As a result, even in black and white, to a generations-later audience that takes high-resolution, full-colour imaging for granted, they come alive.

In other words, no Brownie box camera for Wilmer Gold!

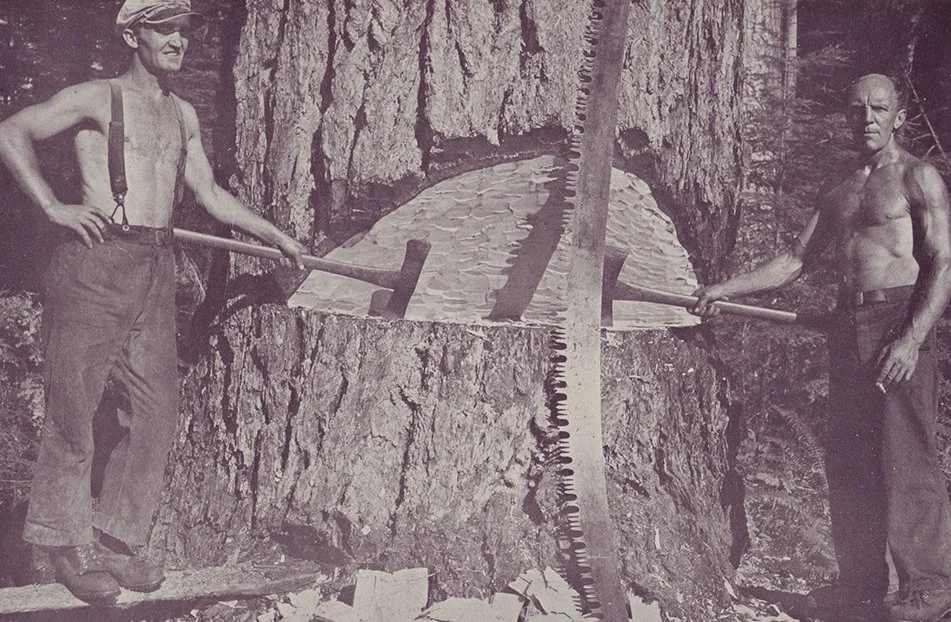

His was a large, heavy and cumbersome camera on a tripod that he had to lug out into the forests. When he’d chosen and composed his subject, such as showing loggers at work, he’d have to try to pose them as if in motion, or ‘freeze’ them at work with an agonizingly slow shutter.

Then came the developing and printing process in a cramped and smelly darkroom where, in the eerie glow of a dim red safe-light, the real challenges of composition and contrast—the instinctive and acquired skills of artistic and mechanical skills and finesse that are essential to achieving a masterpiece instead of a snapshot—began.

Always in black and white, I remind you.

One of the logging photos I’ve acquired on the garage sale-flea market circuit over the years. The caption identifies it as the Comox Logging & Railway Co., Ladysmith, 1937. It sure looks like a Wilmer Gold photo and the time frame is right.

Colour photos often speaks for themselves but black and whites must stand alone. Don’t believe me? Try it sometime. Everyone’s a photographer with their camera and smart phone these days but you can bet few of us are equal to the Wilmer Golds of old who often achieved that last step to perfection in their darkrooms.

Because we are spoiled in this age of point-and-shoot digital photography we likely find it difficult to empathize with the early photographers and their operator-unfriendly equipment which made almost shooting assignments a test of stamina and character, as well as artistry.

For all that, a talented few took the time and trouble, and as a result we’re indebted, all these decades later, that Wilmer Gold and a handful of other skilled industrial photographers set out to chronicle what it was like to work in the woods and in other industrial B.C. workplaces, years ago.

They did so when giant first-growth forests were still felled by hand.

Even when mechanization began to take hold, it was still Jack vs. the Giant, with bulldozers and logging trucks hardly bigger than today’s heavy-duty pickup trucks.

* * * * *

Chronicles readers who’ve visited Lake Cowichan’s Kaatza Station Museum, in particular the old Bell Tower Schoolhouse building, will recognize the name, Wilmer Gold.

Another great find that looks suspiciously like a Wilmer Gold photo, this one captioned, “Power Saw 4, Camp 3, Nov. 1943”. Camp Three was Nitinat at the head of Cowichan Lake.

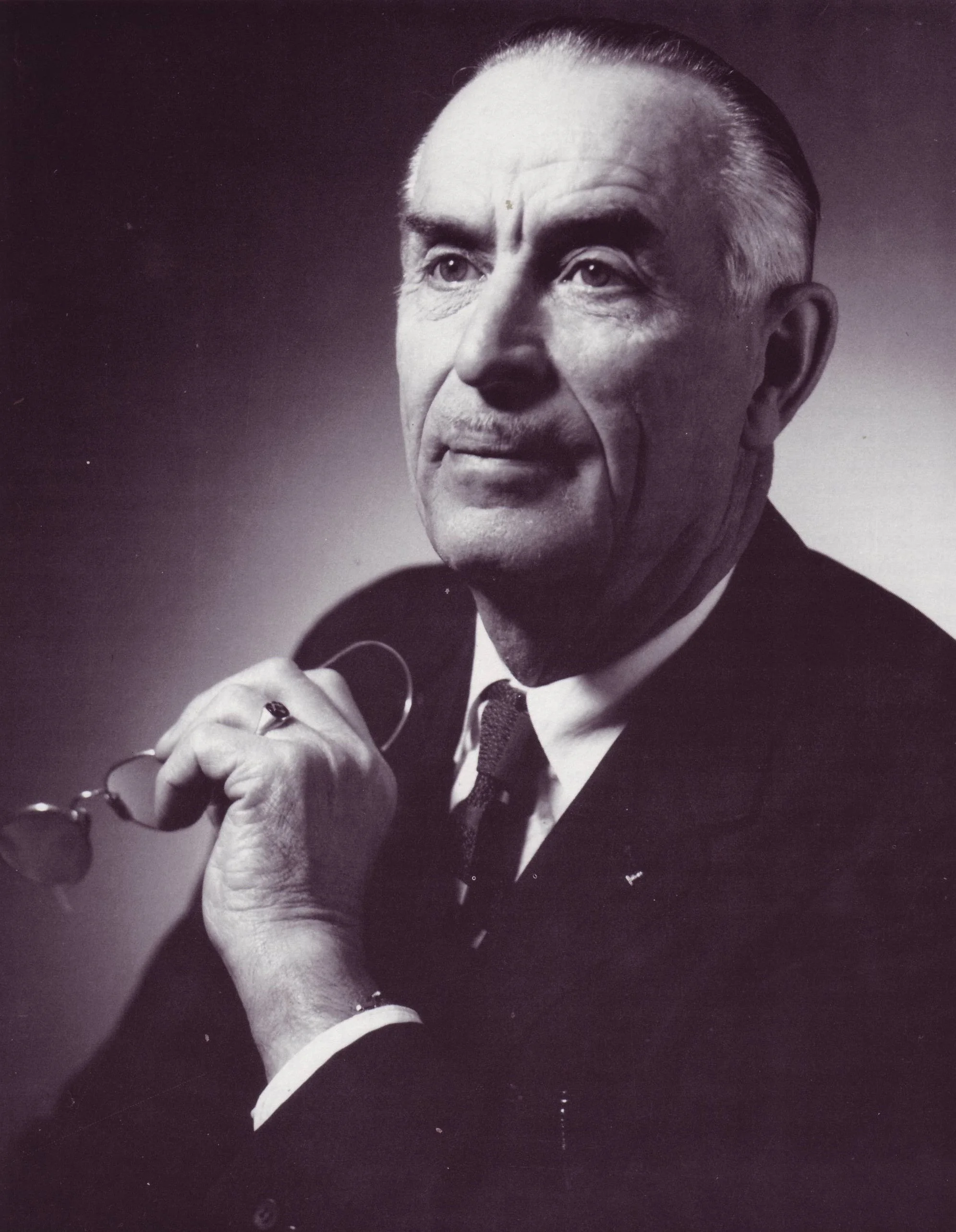

Victoria-born but raised in Alberta, Gold (1917-1992) moved to out-of-the-way and almost off-the-map Youbou in 1934 as a freelance photographer. That was in the middle of the Depression when making a living—any kind of living—was challenging. For the next half-century he chronicled the Cowichan Lake region’s logging industry—one of the reasons why enlargements of his fabulous logging photos form the main display in the school building.

BC Bookworld has termed Gold’s portfolio, photos from which have appeared in Time and Life magazines, “one of first comprehensive studies of B.C. logging”.

But there’s nothing scholarly or journeyman about Wilmer Gold’s work, just fine photography. His camera was his easel and the scenes he has captured for all time are little less than priceless to those of us who follow.

Most of the old-growth forests are gone, all of the pioneer loggers are gone—but Wilmer Gold’s photos are with us forever.

* * * * *

Personal note: I’ve visited Kaatza dozens of times and always find myself studying Gold’s photo gallery in the schoolhouse, sometimes giving it more time than the exhibits in the museum itself. Always, I see something new in these photos, many of which were taken in the late 1930s.

No caption for this one but it sure looks like a Wilmer Gold.

I look at the scenes of old-growth forest, of massive, smoking steam locomotives and donkeys, the coiled cables that glisten like chrome from heavy usage. I study the faces and wonder what became of these men, most of whom are trim and fit in their Stanfields. Logging was a dangerous job; did they go off to war or—?

* * * * *

Wilmer Gold is probably best known for his 1985 hardcover book, Logging As It Was. As I write this, it’s listed (with a five-star rating) on Amazon for $137.22 plus $21.00 shipping—U.S. funds.

A freelancer who relied upon his camera work and the modest rental income from some equally modest cabins on his Youbou property, we shouldn’t be surprised that Gold had a reputation for being, shall we say, frugal.

That Logging As It Was now sells for about $180.00 Canadian must have him spinning in his grave—with envy!

According to the seller, his book is a “fascinating look at the logging industry on Vancouver Island providing a photographic record of many of the major camps, sawmills, pulp mills, railways, and other logging concerns that developed, flourished, faded, were discontinued and dismantled or amalgamated.

“The black and white photos show what life was like out in the woods as well as in the busy camps and...towns. There is also a long section with the memoirs of former workers and family members recounting life in the forestry industry.

“Illustrated throughout with black and white photos. End papers show maps with 24 different logging and sawmill operations pinpointed. 255 pages.”

Several copies of The Golden Years, Gold’s hardcover autobiography which was published by his granddaughter Glenda Dhillon after his death in 1992, have turned up at local garage sales and flea markets in recent years.

Which is just as well, as it’s also listed on Amazon for from $87.75 to $295.00 U.S. plus shipping!

Another great flea market find, provenance unknown, and captioned, “Industrial Timber mills Ltd., Youbou, B.C. Day shift crew , July 21st, 1937”. Is it a Wilmer Gold photo? I think so.

At the golden age of 96, Gold dedicated The Golden Years to his late wife Julia Margaret Holt Gold who, “without reservation,” gave him 49 years as his life’s companion and as the mother of their only child, son Holt Gold, and as family matriarch to five grandchildren and five great-great grandchildren.

It was at granddaughter Glenda Dhillon’s urging that he wrote his memoirs and selected photos from the 1000s he’d taken over his 90 years.

As she explains in the introduction she’d long wanted to know more about her grandparents’ experiences and was delighted when she finally convinced Wilmer to set pen to paper. Making the task all the easier was her discovery that, for over half a century, Grandfather Wilmer had catalogued every photo he’d taken, with names, dates and locations including related trivia or anecdotes.

* * * * *

But I’m going to leave Wilmer Gold’s life story for another time.

Today, I want to promote his wonderful legacy of photographs, most if not all of which are in possession of the Kaatza Station Museum and Archives, Lake Cowichan. Formerly known as the International Woodworkers of America Local 1-80 Collection, they’re now on permanent loan to the museum by the United Steelworkers Local 1-1937.

Taken between 1934-1967, the collection consists of 1477 print photos and 1448 negatives. According to the Kaatza Museum’s website, the collection “was taken by photographer Wilmer Gold, and produced by his wife Julia Margaret Gold. They were purchased by IWA Local 1-80 in 1983 and were initially cared for by Ken McEwan, the Local Union’s newspaper editor.

“Faller, safety expert, and the son of an early union organizer, Allan Lundgren took over caring for them in the late 1990s. In 2007, the Wilmer Gold Collection was moved from its location in Duncan to the Kaatza Station Museum and Archives in Lake Cowichan...

“Photographs show forestry operations and forest worker communities, mainly on South Vancouver Island, during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. The binders of print photographs also contain additional photocopies, notations and meta-data on each photograph.”

Fortunately for posterity, the original Gold photographs are generally in good condition although some of the print photos are bent from improper storage.

The celluloid negatives, subject to deterioration, are stored in a fridge in the Museum’s Bell Tower School which also displays enlarged photos. The lengthy process of digitizing the photos in the collection and making them available online continues.

The man behind the camera, Wilmer Hazelwood Gold, 1972, from The Golden Years. This, of course, is one photo that he didn’t take himself; it’s the work of Corona Photo Studios, Edmonton, AB.

Kaatza Station Museum is always worth a visit; if you go be sure to check out those large Wilmer Gold photos mounted on the walls of the Bell Tower School. Don’t just glance at them but look at them carefully; study the faces of the men and ponder, as I have so many times, who they were and what became of them?

Look carefully, too, at those steam donkeys and locomotives, the first trucks and other logging apparatus of the 1930s and 1940s. Then look at the trees—all first-growth and huge. Nothing at all like the glorified Christmas trees you see on logging trucks today.

This was logging in its Golden Age; who better to have saved it, if only photographically, than Wilmer Gold?