When the cure could be worse than the bite

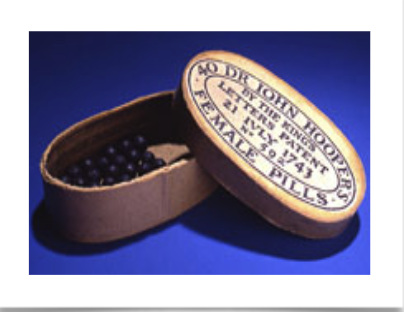

Where are they now, those wonderful patent medicines that promised to relieve every ailment, human and otherwise, from “female complaints” to fallen arches and falling hair?

Alas, they’ve gone, gone the way of the old-fashioned drugstore and the dinosaur. Victims, for the most part, of advances in medicine and tightened drug laws, they’re now part of our vanished heritage.

—americanhistory.si.edu

* * * * *

A faint ‘clink’ of the shovel, some gentle shifting of loosened soil, and the square, aqua green butt of a Davis Painkiller saw the light of day for the first time in a century. It was that long since some unknown workman self-medicated all that ailed him beside the E&N Railway tracks. Tossed over the embankment, the small bottle had landed amongst the shards of an assortment of liquor bottles which, at least, had been sold for what they were, not dispensed in the guise of medicine fit for man or beast.

Long gone was its label which identified the contents as being antiseptic, healing, warming and, taken internally, for chills, common colds, cramps, colic and diarrhea. Perhaps it was its external applications that soothed our anonymous workman’s sprains, bruises, strained muscles, rheumatic pains, minor cuts and scratches, frostbite, insect bites and stings.

That was when it was used as a liniment. It could also be ingested by diluting it, one teaspoonful to a glass of water or milk, to relieve symptoms of sore throat, spasmodic croup and chilblains. It must have worked: when did you last hear someone complain of chilblains?

Not that Perry Davis's Vegetable Painkiller was likely any better nor worse than the thousands of other cure-alls known as patent medicines whose ubiquitous ads in the newspapers and other periodicals claimed to restore, revitalize and rejuvenate, grow hair and do almost everything but wash windows—usually for less than a dollar a bottle.

But some, like Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, were bottled poison.

—artefact.museumofhealthcare.ca

“Advice to Mothers: Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup should always be used for Children Teething. It soothes the Child, softens the Gums, allays all Pain, Cures Wind Colic, and is the Best Remedy for Diarrhoea. Twenty-five cents a bottle.”

God help the mother who dosed her child with Mrs. Winslow’s syrup—it contained so much morphine that it has gone down in medical history as “the baby killer.”

Lydia E. Pinkhlam was a teetotaller in her private life. But business was business and her blood purifier was laced with alcohol. —Wikipedia

On the flip side, one of the greatest successes in patent medicines was also its longest living institution, not succumbing to changing times until 1968, without ever—so far as is known—killing anyone. For almost a century, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound promised to relieve “those painful complaints and weaknesses so common to our best female population” across North America.

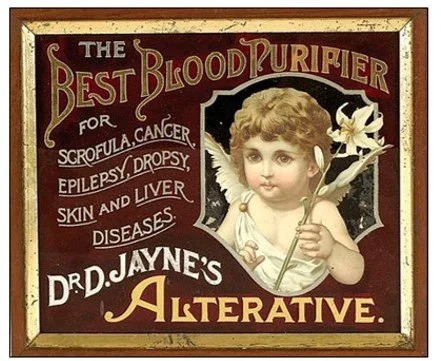

Originally marketed as Lydia E. Pinkham’s Blood Purifier, ads claimed that “This preparation will eradicate every vestige of Humors from the Blood, and at the same time will give tone and strength to the system. It is far superior to any other known remedy for the cure of all diseases arising from impurities of the blood, such as Scrofula, Rheumatism, Cancerous Humor, Erysipelas, Canker, Salt Rheum and Skin Diseases. Sold by all druggists.”

Now even Lydia E. Pinkham is history although derivatives of her vegetable compound are still marketed under different brand names—but without the alcohol content!

* * * * *

History doesn't acknowledge the genius who received the first patent for bottled medicine, although Richard Stoughton was granted the second such patent for his single ‘elixir’ in 1712. Hundreds of others jumped on the bandwagon when it became apparent that such cure-alls that cost pennies to produce by the gallon were, in fact, bottled gold. As even so-called legitimate medicines were primitive and doctors few, most sufferers had little recourse but to endure, to heal naturally or to seek a miracle cure in a bottle.

By the mid-18th century more than 200 so-called ‘proprietary medicines’ were being sold in Britain and in the American colonies, each of them touting a descriptive title (often the name of the discover and vendor), and all claiming to cure every ailment known to humankind, as well as some yet undiagnosed.

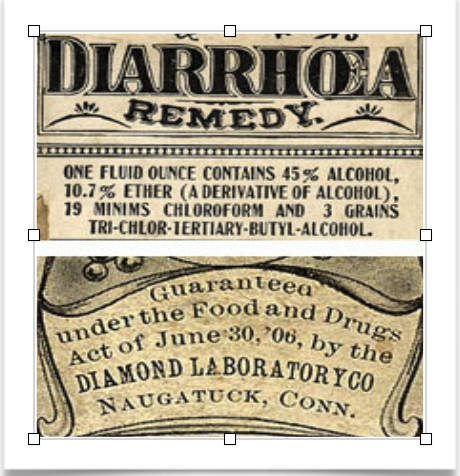

It may not have cured you, but its 45 percent alcohol content probably gave momentary relief! --americanhistory.si.edu

Popular vaudeville, radio and film comedian W.C. Fields liked to lampoon patent medicine vendors who became known as snake oil salesmen. —Wikipedia

Bitters, vegetable compound painkillers, elixirs, liniments, balsams, tonics, panacea... there was no complaint unworthy of the curative attentions of the snake oil salesmen and medicine men who toured the country, hawking their wonderful wares on horseback, from street corners and in travelling medicine shows. Mixing showmanship and oratory, these angels of mercy (mercenary would be more accurate) sold bottled curatives by the barrel on empty promises that bordered on cruelty.

Mixing his own brand of humour with historical fact, the legendary W.C. Fields depicted his version of one such early salesman in several of his films, painting a hilarious portrait of an era not quite gone in his lifetime.

How about these three lads in their sailor suits?

An irony of the so-called patent medicines was that very few were in fact patented; rather, manufacturers simply registered the names of their products as the laws of patent required that the ingredients be listed on the label. This, of course, gave away the recipe and would have revealed the high alcoholic content. Worse, many of these elixirs contained such potent ingredients as opiates; hence, no doubt, their pain killing capabilities.

Discerning consumers soon learned to distinguish the better medicines, one popular ‘bitters’ being rated, upon analysis, at 118 proof!

—americanhistory.si.edu

Perhaps the real secret behind the phenomenal success of patent medicines was the fact that they were the first products to be systematically advertised throughout the U.S. and Canada. Entrepreneurs had early realized that the key to marketing was through the use of mass media which, at that time, consisted of newspapers and handbills. The result was a pioneer version of Madison Avenue, with competing companies spending the bulk of their budgets on colourful, flamboyant ads.

Gimmicks, ranging from trade cards then postcards to fads such as the use of that new-fangled word, electricity, became the name of the game. No symbol, no far-off land was safe from exploitation in the sale of patent medicines. Whatever the key to one’s sales resistance, it was a safe bet that the medicine men could find it and use to their advantage.

It was not long, of course, before the more enterprising began branching farther afield, catering to the want of those wanting to treat yellow teeth, bad breath, acne and other social plaints of both sexes. But it was the medicinal field that offered the greatest sales potential and that’s where most marketers concentrated their efforts with competing advertisements that extolled the wondrous healing powers of their products.

Personal appearance has always been a human priority and the medicine men of old weren’t blind to this market; hence many patent ‘medicines’ qualified as health and beauty aids. —news.cornell.edu

Many of these ads were testimonials, presented as what, today, we term ‘advertorials.’ They were usually written in the first-person as human interest features to make them appear to be news items. Such as this testimonial that appeared in the Nanaimo Free Press in 1920, complete with the eye-catching, news-style headline and subhead:

OPERATION WAS NOT NECESSARY: ‘Fruit-a-tives’ Restored Her to Perfect Health.

In the text, Mme. F. Garneau, Montreal, tells readers that, “For three years I suffered great pain in the lower part of my body, with swelling or bloating. I saw a specialist, who said I must undergo an operation. I refused. I heard about ‘Fruit-a-tives’ so decided to try it. The first box gave great relief; and I continued the treatment. Now my health is excellent—I am free of pain—and I give ‘Fruit-a-tives’ my warmest thanks.”

All that for just 50 cents a box or six boxes for $2.50 (trial size, 25 cents), shipped postpaid!

Note that Dr. Jayne’s ‘Alterative’ also promised to treat cancer and liver diseases. It’s sad to think that many people, unable to afford real medical treatment, put their faith in huckster products such as this one. —www.pinterest.com

Who was Mme. Garneau? Did she receive some form of remuneration for her passionate endorsement? Who knows, but we can guessm although she wasn’t the only Fruit-a-tives fan. John E. Gulderson, a contractor and mason who’d, for five years, so suffered from rheumatism that there were times he couldn’t get up without assistance, and who’d tried other patent medications, also swore to the benefits of this product. Four years previously, he’d seen an ad for Fruit-a-tives and bought a box. When it brought him relief, he continued using it for six months “until the rheumatism was all gone and I have never felt it since.

“Anyone who would care to write to me regards ‘Fruit-a-tives’ I would be glad to tell them what ‘Fruit-a-tives’ did for me.”

Their claims were small when compared to that of Napoleon Girard, described as a prominent contractor and rancher in Edmonton. Chronic indigestion had been his curse for 10 excruciating years. Sometimes, he’d had to fight to get his breath and his heart would “palpitate so terribly that I was beginning to think that I had heart trouble”.

The attacks became so severe that he all but quit eating because of the discomfort that inevitably followed. All that ended when he began to take Taniac. “It proved to be just the very thing I was needing and the change in my condition has simply been remarkable.” No longer troubled by stomach upset, he could again eat whatever pleased him.

Best of all, he felt 20 years younger!

If you had a cold, Peps promised to make your breathing easier; all you had to do was dissolve a Peps tablet in your mouth and your breath would carry the medicinal pine vapour to all parts of your throat, nasal and air passages, destroying all germs as it soothed and healed the inflamed membranes. Not only did it bring immediate relief but Peps fortified you against coughs, colds, sore throat, bronchitis and grippe.

Available at drugstores and stores for 50 cents a box, or you could mail a copy of the ad with your address and a one-cent stamp to the Toronto warehouse for a free sample.

* * * * *

—www.history.com

How many of these so-called cure-alls really did bring relief, if not a cure, to their users, we’ll never know. It has been surmised that their real ‘healing’ value, if indeed such there were, lay in those ubiquitous and blatant claims of success. Meaning that, if you believed in a product’s claims strongly enough, of if you were truly desperate enough, you might imagine, or even will yourself, into believing that you felt better, even cured.

Which might have prompted you to write a hearty and heartfelt endorsement for publication.

Mind you, the fact that so many early patent medicines were composed mainly of alcohol and opiates certainly must have made some users feel better, if only temporarily.

* * * * *

It was the discovery that most so-called medicines pedalled by the gross across the continent and in Britain were composed mostly of alcohol, opiates are common herbs with no proven medicinal qualities, that resulted in federal legislation that dealt a death blow to most peddlers of patents (an estimated 50,000 in the first decade of the 20th century). Those who survived were forced to change their advertisements and to tone down their curative claims.

* * * * *

Several of the illustrations that accompany today’s Chronicle are trade cards which were used to extol the various patent medicines and other health and beauty products of that time (although trade cards go back as far as the 1600s). Usually smaller than a (3.5x5) postcard, these colourful pieces of promotion were inserted in cartons at the factory, distributed door to door as part of an advertising campaign or, more often, handed out at the corner grocery and drugstore.

Although intended as a means of promoting a product, many of these cards showed such taste in artistic design and printing techniques that they became prized by many adults and youngsters who built large collections by saving and trading them with friends.

Here’s a great example of why trade cards, which long predated sports cards, have had a revival of interest by collectors. —arnoldltradecards.com

Supplanted by mass-circulation magazines and newspapers, they were thrown or tucked away and forgotten. But, with the arrival of bottle collecting in the 1960s, 1000s of these trade cards were exhumed from attics, dusty drawers and old scrapbooks and, for a second time, became popular collectibles. When I began collecting them years ago, they usually sold for less than a dollar. Now, online, rare ones go for as much as $100 US.

* * * * *

Some Chronicles readers are sure to have memories, perhaps distant ones, of some of the last surviving patent medicines. A Carter's Little Liver pill anyone?