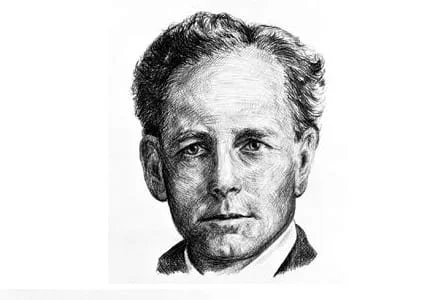

William Wallace Gibson: ‘Birdman’ of Victoria

As did Alcatraz so too did Victoria have its “birdman.”

Whereas Robert Stroud, a twice convicted murderer, made himself famous through his studies of birds, William W. Gibson achieved immortality by being Victoria’s—Canada’s—Wright Brothers in one.

On Sept. 8, 1910, William Gibson flew one of the first Canadian-built airplanes in all of Canada. (*See: Postscript.) His “Twin-plane” crashed during its second flight but Wallace survived.

I was reminded of this Canadian aviation pioneer by a recent small article in the Times Colonist: Three hectares of the Lansdowne Middle School are being sold for a new French language school.

The connection is this: Lansdowne Middle School and the acres and acres of flat land around it, now all developed as a commercial and residential neighbourhood, was the site of Victoria’s first airport.

But even before the airport, there was aviation activity there—William Gibson’s pioneer attempts to fly his own heavier-than-air, engine-powered aircraft.

‘Birdman’ was the name that doubters and detractors gave him, even laughingly flapping their arms when they met him in the streets.

But he persevered—and he flew.

* * * * *

William Wallace Gibson. —1000 Towns of Canada

“For nature’s plan was ne’er intended.

That man through space should be suspended,

And naught but fool, a bird would make,

Or nature’s secrets try to take.”

In these lilting couplets did William Wallace Gibson—“Birdman of Victoria”—recall the mocking skepticism which surrounded his efforts to fly a heavier-than-air craft, 110 years ago.

But time has vindicated Gibson’s faith; today history acknowledges the miracle that this unassuming Scotsman achieved with blacksmith’s forge, sticks and canvas one summer morning in a quiet cow pasture at the base of Mount Tolmie.

Born in Dallmellington, Ayreshire, in 1876, Gibson was the fourth of four boys and a girl. He was seven years old when the family sailed for Quebec, April 25, 1883. After a “rough and sickly” 13-day voyage the family landed at the historic city. Settling at Wolseley, Sask., the Gibsons’ nearest neighbours were Chief Piapot’s band of Cree.

For the next three years, young William enjoyed a Tom Sawyer existence with the Cree children, free of school. Soon ‘Jumping Deer’ could hunt with bow and arrow as good as his friends.

At 13—after three years’ schooling—it became William’s duty to shepherd the family’s growing herd of cattle and horses. The keen youngster soon learned he could devote his talents to other fields on windy days as the herd would graze into the breeze to escape the flies. During these lazy hours William turned with increasing intrigue to the mysteries of flight.

With his newly-found interest came “the first passenger flight in the Dominion of Canada”!

His initial experiments as the herd grazed contentedly over the plain, were with kites. Time and again, the marvelling lad charged across the plain on his pony, a kite trailing behind on baling wire. With each design he learned to keep his creations airborne longer and to soar them higher and higher.

Then he developed the scheme of snaring gophers, placing them in cardboard boxes, and sending them aloft on the tail of a kite. “I could only keep them in the air for about an hour,” he wrote long after, “because some of them became deathly sick, and when I brought them down they sat on the grass with their eyes half-closed for about two minutes before they scampered off to find their holes.”

With this observation came a plan to increase the duration of the passengers’ flights by making conditions more comfortable. To this end he created a dome-shaped basket of willow wands. The young inventor had chosen willow for two reasons. Firstly, to cut wind resistance, secondly, to allow his gophers to enjoy the view!

With each successful flight, William’s plans advanced. Finally, one windy May afternoon, he launched his masterpiece: a seven-foot blue kite with nine passengers!

For an hour he sailed the enormous kite until his arm tired, so he tied the string to a rail fence. He then lay on the grass “to ponder and see visions of powered flight”.

His reverie ended abruptly when the kite plummeted to earth, killing all on board. “Anxious to know what had caused the crash, William inspected the wreckage. His probing eye soon discovered that one of the gophers had chewed through the cord securing the basket to the kite. The mystery was solved. The rueful inventor, sadly noting what he believed to be “the first air casualties in Canada,” vowed to use brass wire in future flights.

With adulthood, Gibson had to forsake his experiments for a livelihood by opening a blacksmith shop in Wolseley, Business prospered and, in 1901, he bought out a bankrupt hardware merchant for $3000 and shipped the inventory to Balgonie.

Again, all seems to have gone well as he was soon devoting spare hours to his old hobby.

He turned his attention to building models of airplanes. Remembering how he’d flown kites on calm days by towing them behind his galloping pony, he pondered means of powering his creations The blacksmith and hardware merchant had as yet never heard of propellers or gasoline engines.

In 1903 he heard the momentous news that two Americans named Wright had successfully flown a machine at Kitty Hawk, N.C. Inspired, he redoubled his efforts, building paper models with which he practised continually, seeking a design which would support an engine. Making his work all the more difficult was the fact he had to advance step by painful step, improvising all the way. He hadn’t seen seen a picture of the Wright craft; all he had to work with were some boyhood memories of kites.

Coincidentally, he work progressed along the lines of that of the much enlightened Professor Samuel Langley whose remarkable accomplishments in the U.S. had earned him only ridicule.

Gibson hadn’t heard of the hapless professor, either.

He described one advanced model as being “two small kites, one behind the other”. With a wingspread of 20 inches, it was powered by the spring of a window-blind roller which doubled as fuselage. Control was achieved through changing the angle of the forward plane while the rear plane remained stationary at an angle Gibson had found to be successful with kites.

“The window-blind roller was the backbone of the plane,” he explained. “I trimmed the spring end of the roller to 1-16-inch to lighten it and the solid part I cut down to one-quarter diameter and wrapped the whole length with linen thread. The steel end that projected from the roller I lightened by filing and I soldered a small screw to fasten the propeller to.”

He carved a 10-inch propeller from Spanish mahogany then constructed a launching ramp 10 inches wide by nine feet long, with a vane down the centre to guide the “plane.” When he’d varnished and polished it “like glass,” he fastened 12-inch legs to one end, three-foot-legs to the other.

Another problem had been that of secrecy. “At the time,” he recounted, “I had a general store in Balgonie, branch hardware stores in Craven and Cupar, and had considerable money borrowed from the local bank.

“I was afraid if my bankers heard of or saw me playing with such contraptions, they would think I had gone crazy and call in their loan, and perhaps ruin my business.

“Also, at that time, the [North West Mounted Police] had authority to pick up anyone reported queer and take them to Regina. Gossip travels at great speed, so I decided to keep my experiments secret.”

One dawn in June 1904, Gibson crept to the roof of a downtown building with his model, set it carefully onto the launching ramp, wound the propeller spring and stepped back. Propeller spinning eagerly, the small craft leaped from its rail and was airborne, soaring across the street to crash into a boxcar 130 feet distant.

A wing was damaged but the ecstatic Gibson cared not: “I had proved beyond a doubt that I could build a machine that would fly!”

In following months many a sunrise would find the eager inventor on the roof, launching models of various designs. As ever, Gibson exercised every precaution to remain unobserved. One day the local doctor visited him to tell the alarmed merchant he’d seen him on the roof that morning.

As Gibson stiffened, heart pumping violently, D. Kaulbfleisch had blithely continued, “Billy, that was a funny looking bird you were trying to catch...this morning. I never saw any bird like that in my life. It flew right over my buggy and lit on the grass over by the station!”

Encouraged by success, Gibson resolved to build a full-scale model on his farm. He’d almost completed a four-cylinder, four-cycle engine for it when he heard of an opportunity to contract for 42 miles of the building Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

“I lost $40,000 in 18 months,” he recalled, ruefully.

When he finally paid off all debts, Gibson was almost broke. He decided to start afresh and moved to Victoria. Here, he met veteran prospector Locky Grant, who offered to sell him a gold mine near Clayouot. Although penniless, Gibson agreed to look it over.

He reached the mine in 10 days, travelling up the Island’s rugged west coast in a 17-foot motorboat. He was seasick most of the way, almost swamped himself several times, and drifted ashore where he was fed by residents. By the time he reached Clayoquot he’d lost 28 pounds.

When Grant showed him a pan of nuggets, Gibson “took one look at it and got gold fever”. For $100, his boat, camera, telescope and rifle, he became owner. Before long he had the mine in production, built a stamping mill and poured the first gold brick from a west coast Island quartz mine.

Selling out for $10,000, he returned to his old dream of flying.

Again solvent, he had his four-cylinder engine shipped from Balgonie. He soon finished it but found its six-inch stroke much too long—“It jumped around like a chicken with its head chopped off.”

Undaunted, he designed a two-cylinder, six-cycle, air-cooled model. Constructed at Hutchinson Brothers’ machine shop in Esquimalt, the engine, first of its kind built in Canada, and now displayed in the National Museum at Ottawa, developed 60 horsepower.

From morning till night, week in and week out, the Hutchinsons’ forges glowed hot as Gibson hammered bits and pieces of steel into an engine. He handcrafted virtually every part himself; even the more than 100 bolts which were bored hollow to save weight.

Months passed, Gibson working steadily with his silent partner known only to history as “Dave.”

“With spruce and cedar, silk and wire,

Our bird began to show attire.”

Motorcycle wheels proved too weak so he had a set custom-made at Thomas Plimley’s auto dealership.

Finally came the great day. Twice before all had seemed ready but, at the last moment, the anxious inventors had detected weakened struts, propeller blades too long, the engine improperly placed. This time they were ready.

On the evening of Sept. 7, 1910, the ‘Twin-Plane’ waited quietly in a circus tent near Mount Tolmie. With prospector Locky Grant as sentry, Gibson and Dave had completed their final rehearsal. The next morning, as Victorians slept in ignorance, they’d make history.

With a skeleton of spruce, the ugly craft had two enormous wings, each 20 feet by eight, and covered with blue tent silk from Jeune Brothers, which gave 300 square feet of lift. Fifty feet long, the plane’s unique features included 100 springs for flexibility. The engine, with a larger propeller forward, and a second, aft, straddled the frame’s centre.

With the first feeble rays of dawn, the trio had towed the ungainly creation into the pasture. The monster roared to life instantly when Gibson spun the propeller then climbed into the seat—a horse saddle. Hands at the controls, tense with excitement—and fear—he nodded to Grant to release the plane.

Bucking wildly, the giant bat sped across the field then, sniffing the dawn air hungrily, zoomed skyward in a long, lazy arch, bumping heavily to earth seconds later, 200 feet from her starting position. When the engine stuttered into silence, peace reigned over the pasture once more.

William W. Wallace had flown!

“Local aviator makes aeroplane and flies,” cried the Victoria Daily Times headlines that afternoon. Despite the inventors’ secrecy, word had spread rapidly of the momentous occasion, the Times noting “a machine of the originality and size of an aeroplane...cannot be handled at daybreak or at dusk for long without its discovery becoming known.”

A broken wheel, reported the newspaper, was delaying further flights.

“May the ingenious and plucky birdman have all kinds of good luck,” wished the Colonist.

Amazingly, Victorians weren’t impressed. Instead of hailing Gibson as a genius, even his friends laughed rudely, called him “Birdman” and, when passing him in the street, would flap their arms and laugh. Others would point skyward, grin, then cover their faces. One clergyman went so far as to solemnly urge Gibson to give up his wild venture for the sake of his family, that it was the devil urging him on.

But Gibson had tasted success; he couldn’t quit.

Two weeks later, the twin-plane was repaired. Again, Gibson started the engine, again the propellers whirled furiously and he climbed into the saddle-seat. And again his partners released the craft. Seconds later the craft soared through space, its elated pilot working the elevators and rudders happily.

Suddenly, the twin-plane veered to the right. Panicking, Gibson levered the rudder in the wrong direction. A split second later, the craft smashed into an oak tree at 40 miles per hour (60kph) then tumbled, lifeless, to the ground. Gibson was thrown clear, crushing two fingers and gashing his head; he carried the latter scars for life.

His wonderful twin-plane was a total wreck.

Not discouraged, Gibson immediately set about building the Multi-Plane. This time, wary of oak trees, he obtained permission from Lieutenant Governor Thomas Paterson to test the new raft on his farm at Ladner. Unfortunately, wet weather weakened the laminated spruce frames, forcing another move to Kamloops.

Other difficulties resulted in a third shift, this time to Calgary. There, in the dry prairie air, his Multi-Plane performed several successful flights. Gibson dreamed of operating his own aircraft plant.

Sadly, on Aug. 11, 1912, while landing, the test pilot crashed while trying to avoid some badger holes. The pilot escaped without serious injury but the Multi-Plane was ruined.

Gibson had lost a fortune--$20,000--in attempting to prove heavier-than-air flight was feasible. This time he had to consider his family. The crash of his Multi-Plane in an Alberta field marked the end of the ingenious pioneer’s battle to fly.

In 1945, members of the Piapot Reserve where Gibson had played as a boy, made him an honorary chieftain of the Cree nations, naming him Chief Kisikaw Wawasam—“Flash-in-the-sky-boy.”

The engine from Gibson’s historic plane is located in the National Aviation Museum in Ottawa. A replica of the airplane is located in the Smithsonian Museum in New York, and the B.C. Aviation Museum in Victoria.

* * * * *

Post Script:

The first powered heavier-than-air flight in Canada occurred on Bras d’or Lake at Baddeck, Nova Scotia on Feb. 23, 1909 when John Alexander Douglas McCurdy piloted the AEA Silver Dart on a flight of less than 1 kilometre. —Wikipedia

The first Canadian-built aeroplane was built by Reginald Funt on 8 September 1909 at Edmonton. —Military historian William Paul Ferguson.

* * * * *

Courtesy of Chronicles reader, friend, great photographer and avid hiker Bill Irvine, these shots of the historic sites monument and the school that now occupy the onetime farmer’s field where William Gibson successfully flew in September 1910. —Bill Irvine

Last week’s promo for today’s post prompted this reminisce from Bill:

“Your [forthcoming] William Gibson ‘Birdman’ article is close to my heart as a former licensed instrument pilot and owner of two different airplanes... We flew out of Victoria CYYJ Airport for a decade starting in 1977. We also photographed the Lansdowne Field commemorative cairns in 2015... I remember seeing planes take off and land c.1944 even after the strip was officially closed. Lansdowne Field was less than a kilometre from our home on Doncaster Drive.

“Your Greater Victoria School District, Lansdowne South Campus land sale is also familiar to me. This parcel is bordered by Bowker (not Bough-ker) Creek which paralleled Doncaster Drive (right across the street) from where we lived in the mid-forties. The creek was all open-air in those days but now is mostly underground on its way to Oak Bay.

“A trapper had a registered trap line for the creek and as the supply of muskrats was running low, he gave us — through my older brother, Gerald — permission to trap the furry creatures. So we did. Bet you never knew I was trapper, Tom! We can both agree there's been a lot of changes in Victoria since 1944.”

Indeed, Bill, indeed!

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.