The Royal BC Museum has certainly been in the news lately—most of it bad, unfortunately.

You’ve needed a program to follow recent developments: resignations; charges of in-house racial discrimination; a much beloved exhibit demolished then, oh, cancel that, it’s still here and we’ll reopen it after making it more multi-culturally palatable;

The buildings are in danger of sinking into the sea mud if there’s a serious earthquake so we’re going to tear them down and rebuild over seven years at the cost of billions of dollars while we strangle the vital Inner Harbour area with demolition and construction activity. No, cancel that, we’ll make do with what we have while we take a few years to think and talk this out...

Have I overlooked anything?

At least this month’s climate action protest with red paint daubed on the iconic mastodon’s tusks couldn’t be blamed on RBC mismanagement.

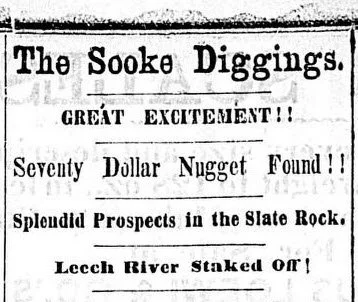

But the Chronicles isn’t meant to be a soapbox and this isn’t even my weekly editorial. So let’s go back to the very beginning of our senior museum and archives. It all started in October 1886 in a room just 15 by 20 feet—the size of a single-car garage!

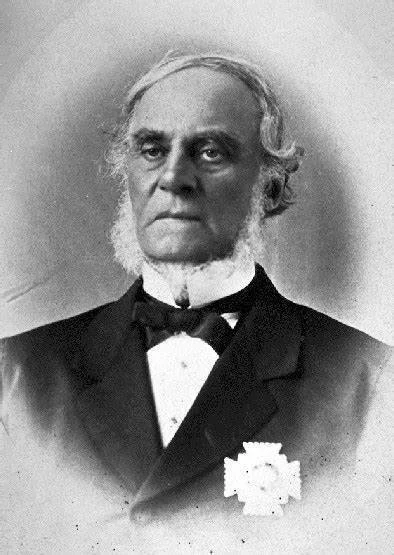

The man who did so much to create today’s RBC by donating his personal collection of stuffed and mounted birds and animals was Jack Fannin, a noted naturalist of his day.

These latest fumbles by management and government must have him spinning in his grave.

That’s next week in the Chronicles.

* * * * *

PHOTO: Would you believe, looking at it, that the Royal BC Museum is at risk of collapsing in a major earthquake? No problem!—Wikipedia photo

Read More