A Murderer’s Love Story

It’s so easy to just go with the obvious, to accept old newspaper accounts at face value. After all, the story is exciting enough that others have done it before you, so why look a gift horse in the mouth?

Heck, I’ve done it many times!

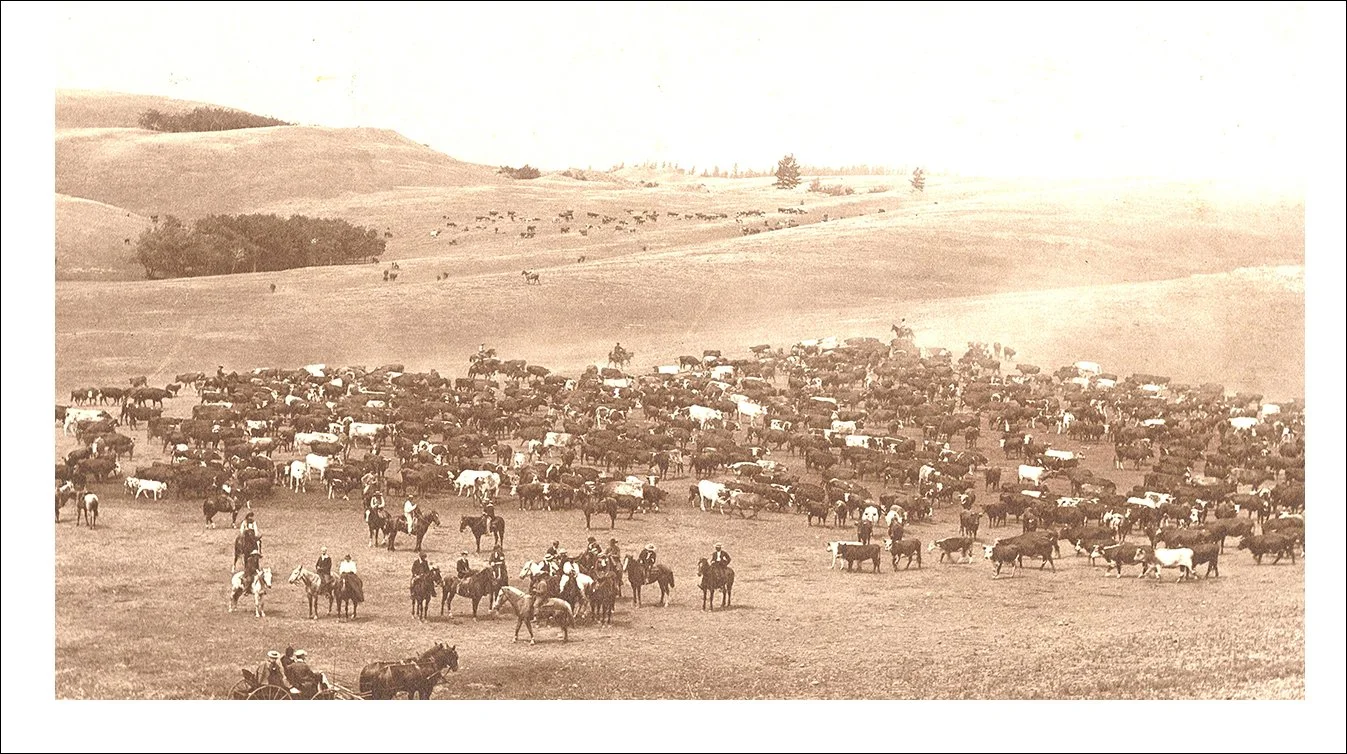

While on the run from the law below the border, Frank Spencer lay low on a Kamloops area cattle ranch. —SJ Thompson UBC Open Collections

But recently, while researching another subject, I came upon an article—ah, the wonders of the digital age—in an 1890 edition of the Winnipeg Chronicle.

Winnipeg, need I say it, is a long way from British Columbia, but the Tribune story, prompted by a hanging in Kamloops, added a new dimension to the accepted story of American outlaw Frank Spencer. He’d escaped a previous date with the executioner below the line, it was said, then killed one man too many, this one above the 49th parallel where British justice prevailed.

Such is the accepted story, which reads like something out of the American Wild West. But is there more?

Of course there is; “life” is layered. And so it was with Frank Spencer.

I’ve told his story—as I knew it at the time—in my book, Outlaws of the Canadian West. Courtesy of the Winnipeg Tribune and the Rev. T.W. Hall who attended to Spencer during his last hours while awaiting the gallows, I tell the story today—but through a slightly different lens.

* * * * *

Morning, July 21, 1890, broke bright and clear.

For some time the little town of Kamloops continued to sleep soundly. Then an occasional column of smoke indicated that early risers were preparing for breakfast, and another day had begun.

As far as 36-year-old Frank Spencer was concerned, morning had come all too soon. As he nervously paced his cell, the light outside his window steadily brightened. For hours, he’d hobbled back and forth, dragging his leg irons, unable to sleep. When a guard quietly asked what he wanted for breakfast, he asked only for a cup of tea.

Then the metallic click of a key in the lock told him that his first visitors had arrived, and, with a relieved smile, he greeted the two be-robed figures. A third visitor was not as welcome; jailer Sinclair having arrived, hammer and cold chisel in hand, to remove the leg irons. Then all waited impatiently for the ringing of iron to cease.

Minutes later, Sinclair was finished, and two late-comers joined those in the crowded cell. Spencer, looking out the window, stared, fascinated, at the gangling wooden structure to which workmen had just given the finishing touches. Then, with a slight shudder, he turned to the others.

It was time to go.

As noted, July 21, 1890, had arrived with terrifying suddenness for Spencer. But those who knew him, and of his career below the 49th parallel, could only marvel that his date with justice had been so long in coming. For violence was no stranger to the lanky Tennesseean. During 20 of his 36 years, he’d been involved in one scrape after another, having drifted with fortune’s tide throughout the American southwest since the age of 16.

By the time of his arrival in British Columbia’s Similkameen Valley, in 1886, the Tennessee cowboy could boast of having known Dodge City in its riproaring heyday, and such illuminaries as Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. In Tombstone he’d ridden with the Clanton brothers–at least until their historic and ill-fated encounter with Earp and Doc Holliday in the O.K. Corral. Then it was on to Colorado, Montana, and the future province of Alberta; the latter step, Spencer’s first outside the United States, being but one ahead of vigilantes fed up with his handiwork with a branding iron.

By all accounts, Frank Spencer was a good horse wrangler: but whisky was his downfall — BC Archives

After a stretch as a cowhand, Spencer headed westward once more; this time to the boomtown of Kamloops, in the summer of 1886. Despite the differences between the free and easy towns below the border and Kamloops, then bursting with expectations for a prosperous future, Spencer seems to have found it to his liking and he found work as a cowhand on the Campbell Ranch, 10 miles east of town. Throughout the wicked winter of ’86, the retired gunman and rustler kept his nose clean; except on paydays, when he would drown the past in cheap liquor in a Kamloops saloon, or in the Campbell bunkhouse.

This seems to have been the lifestyle for his fellow ranch hands as well. Besides sharing their jobs and quarters, they also shared the occasional bottle; a camaraderie which ended with sudden violence on the evening of May 20, 1887.

That Friday, Spencer was going into town and Pete Foster, a 22-year-old French Canadian, handed him five dollars with the request that he bring back four bottles of whisky. To this, Spencer agreed and, later that day, he headed back to the Campbell ranch with Foster’s order. He didn’t go far before he was struck by the thought that such a favour was worth a small commission. This in mind, he pulled the cork from a bottle and tilted it to his lips.

By the time he reached the ranch, Spencer was feeling no pain, and the opened bottle was almost consumed. When Foster met him at the corral, eager to receive his shipment, Spencer handed him the three full bottles and casually waved the empty as notice of his having taken his “share.”

Foster was furious. He worked damn hard for his money. Who the hell did Spencer think he was, drinking his whisky?

Voice rising, Foster demanded restitution. Spencer responded with a shrug and continued to unsaddle his horse. With an oath, Foster seized him by the shoulder, spun him around, and lashed out with his fist. The blow sent Spencer reeling against the fence, where he quickly caught himself and regained his feet. As the young Montrealer closed in, Spencer reached desperately for an equalizer. In all of his years below the line, he’d done his fighting with pistol, rifle and knife, and he wasn’t about to change his style now–particularly as Foster would likely beat him to a pulp.

Grabbing the knife from his belt, he faced his antagonist with renewed confidence. But Foster, as angry as he was, wasn’t intent upon committing suicide and turned to run, Spencer in pursuit. Foster, however, had little difficulty in eluding him and when Spencer soon gave up the chase, Foster, thinking the incident over, returned to the bunkhouse. He didn’t realize that Spencer, fired with cheap whisky and the “code of the West,” was determined to settle the matter the way they did in Dodge City and Tombstone. Hurrying into Campbell’s house, he snatched his employer’s Winchester from the wall and charged outside.

Foster, upon spotting the rifle, began to run for cover–just as Spencer levered a round into the breech, snapped the rifle to his shoulder and, with the speed and motion of a man long used to such situations, fired at the running figure. The .44 calibre slug penetrated Foster’s right arm, passed through his stomach and lodged in his left side, spinning him to the ground before any of the horrified ranch hands could move to stop him.

Almost by reflex, a now sober Spencer headed for the stable at a run, as the others raced to Foster’s aid.

Once inside, Spencer saddled his employer’s fastest bay and led it into the yard. Then, leaping into the saddle, he waved the stolen Winchester, cautioned the others that he would use it again if he had to, and rode away.

But the others were more concerned with getting Foster to hospital. Even before the gunman was out of sight, they were harnessing a team and wagon and preparing the wounded man for the long ride to town. When they finally reached the hospital, Dr. Tunstall removed the bullet. But Foster’s condition steadily worsened and, at 4 o’clock the next morning, he died.

The body was still warm when the inquest was opened in the Kamloops courthouse. The verdict was as promptly delivered: “That Pete Foster came to his death by means of a rifle ball, shot from a rifle in the hands of Frank Spencer and that he [Spencer] is guilty of wilful murder.”

Despite the determined efforts of Provincial Police and Indian trackers, Spencer easily eluded pursuit. Keeping off the main trails and camping without a fire, he worked his way south towards the Washington border. A week after shooting Foster, he crossed the line.

Five weeks after he vanished, his former employer wanted his horse back and advertised to that effect in the Kamloops Sentinel:

STOLEN! FROM L. CAMPBELL’S RANCH

By Frank Spencer, a horse, saddle and bridle; and a .44 calibre Winchester repeating rifle. The horse was a bay, with part of its forehead white, and branded Lc on the left shoulder; the saddle was of California make, double cinch, and block stirrup; narrow; the bridle had hand made reins and snaffle bit. Anyone delivering the same to the undersigned at Kamloops will be suitably rewarded.

L. CAMPBELL, June 25, 1887.

But Campbell’s horse wasn’t to be found–and neither was Frank Spencer. Safe on American soil, he vanished. In actual fact, he’d gone only as far as the Snake River country of Washington, then Oregon, where he again worked as a cowhand. Two years passed without a word of the Kamloops killer and B.C. Provincial Police, although they had not forgotten him, gave less and less attention to the yellowing wanted circulars, as more pressing cases developed.

And on that unsatisfactory note the Frank Spencer case might well have ended–had he not pressed his luck one last time. In the spring of 1889, Spencer again headed for the Canadian border.

This time, he was one of a number of cowboys escorting a herd of horses to New Westminster for an Oregon rancher. When, days after, they were paid off, they headed for the nearest saloons. Spencer, fingering the bills in his pocket, looked forward to some relaxation before heading back across the border.

As he stood at the bar, who should grasp his elbow but Sgt. McLaren of the BC Provincial Police. —BC Archives

For days, he haunted the bars lining Columbia Street, as his money dwindled. With elbows on the bar, and a bottle before him, he didn’t notice the policeman enter the saloon and push his way through the crowd. Then Sgt. McLaren, in firm voice, and with hand on the drinker’s shoulder, told him that he was under arrest. Spencer was struck dumb with amazement. It had never occurred to him that he might be recognized in New Westminster. Yet here was this policeman, snapping handcuffs on his wrists and leading him away.

Out in the street and on their way to jail, Spencer could do little more than protest that it was a case of mistaken identity.

That fall, a preliminary hearing was held before Kamloops Justice of the Peace, James McIntosh, with W.H. Whittaker appearing for the defence. The first day lasted three and a half hours, with eight witnesses formally identifying the prisoner as Frank Spencer. Then the hearing was remanded until other witnesses could get to town. Spencer was returned to his cell where a reporter from the Inland Sentinel, who obviously knew nothing of his career as an outlaw, described him as “yet comparatively speaking, a young man. He does not present the appearance of a man who would commit so serious a crime as that with which he is charged.”

Bound over to the Spring Assizes of 1890, Spencer was duly convicted of Foster’s murder and given over to the care of jailer Sinclair. Then the days fled by all too swiftly, and it was morning of July 21, 1890.

The last hours were the longest. Spencer, unable to sleep at the end, ignored his leg irons to pace his 60-square-foot cell. Then, with the arrival of his two spiritual advisors, the removal of the irons by Sinclair, and the arrival of Sheriff Pemberton and Fred Hussey of the Provincial Police, the death procession was formed.

As they prepared to leave the cell, Spencer made a last request. In a final symbolic gesture to the wild and woolly west of his past, he asked for a pair of slippers; explaining that he didn’t wish to die with his boots on. These were immediately brought and Spencer, having overcome his nervousness of the night, stepped firmly towards the scaffold, mounted the steps, took his position on the trap, and shook hands with all but his black-hooded executioner.

The hangman adjusted the noose and put the white hood in place, as Spencer mumbled a prayer. —Wikipedia

When the Tennessee outlaw finished, he was seen to tremble slightly and Sheriff Pemberton nodded to the executioner to let the trap drop. Death was said to have been instantaneous and, as a final note in the career of Frank Spencer, a Kamloops correspondent noted that the hangman, who’d worn a hood so as to conceal his identity, was from Victoria and well-known.

* * * * *

Such is the accepted story of American outlaw Frank Spencer. That’s the way I wrote it years ago and the way most other writers have written the story. But is there more to the story than this?

According to my most latest research, there is.

What follows is Rev. T. W. Hall’s account of his attending Frank Spencer during his final days and hours in the Kamloops jail. If we can believe Frank Spencer, it throws a whole new light on his tragic and short life. Wild American outlaw or just a young country boy gone wrong?

I leave it to Chronicles readers to judge for themselves.

A Murderer’s Love Story

"SPENCER" OF KAMLOOPS.

A Clergyman Gives an Interesting History of the Man.

The Rev. T. W. Hall, who attended Frank Spencer, who was hanged at Kamloops last week, during his last hours on earth, and who had visited him almost daily for six weeks previous to his execution, relates the following particulars of the unfortunate man's life:

To begin with his name was not Spencer at all, but he did not reveal his right name, dying with the secret, so that his sisters might not learn of his act and terrible fate. He was 34 years of age, and was born in eastern Tennessee. When he was 11 years of age his father and two brothers were killed in the American Civil War.

Shortly after this his mother died and he left his sisters to begin life on his own account.

He went westward spending most of his life as a cowboy on the ranges of the Western States. Six years ago he met a young woman in eastern Montana, became engaged to her, and induced her to leave her parents and go and live with him on a ranch in the northern part of the state.

They lived together a quasi-married life for a year, when Spencer left her in charge of an old couple near where they had lived and crossed the line into Canadian territory. He engaged with a Lethbridge lumberman to cut timber in the vicinity of that place. Owing to a misunderstanding he, to use his own words, had some trouble with the boss, who threatened to take his life. It was of a serious nature, but he solemnly declared it was not criminal, and Spencer, to avoid trouble, came to Kamloops and engaged for a time as hostler at the Cosmopolitan Hotel, and finally with Mr. L. Campbell to work on his ranch.

The particulars of his killing of William Foster on the 25th of May, 1887, in a drunken quarrel, are well known.

After leaving Campbell's ranch he crossed the border, going through Washington into the state of Oregon. After working around on odd jobs for some time he again entered service on a stock ranch... A few days before his return to British Columbia he got on a spree.

He was returning home lightly intoxicated when he was persuaded to join with some of his companions in driving a band of horses to [New] Westminster for one McLeod. He remained around hunting for McLeod, when he was identified, arrested and brought back to Kamloops.

While working with Mr. Campbell he had written several letters to his fiancee in Montana, intending to get married and settle down here, but received no reply.

On his return to the States he made inquiries among his "chums" of the past and learned that she had gone to Utah, and he never heard of her again. One of Spencer's great troubles before he died was the welfare of this young woman. He said he would give the wealth of the world if he owned it, to make atonement to her.

He denied to the last the statements to the effect that he had killed other men, or was wanted across the border for any other crime. He had shot at Indians in self-defence, he admitted, when attacked by them, but never knew if he killed any or not.

To the use of whisky he attributed all the evil that befell him.

It was under the influence of it he shot Foster, and it was also under its influence he returned to British Columbia to pay the penalty of his crime. Shortly before his execution he was offered a drink of whisky or brandy by the sheriff, but he refused it, saying it had been the ruin of his life, and he would face death without it.