Editorially speaking…

Never let the facts get in the way of a good story. Was it Farley Mowat who said that?

I was reminded of his alleged quote when a lady suggested that, perhaps, I should change my initials to B.S. Paterson. She was joking, of course. Wasn't she?

She came to mind when a friend e-mailed to ask about the shooting of Joe Dougan at Cobble Hill in 1890. After he told me what he knew of the tragedy, I had to inform him that his previous informant was so far off the mark that he could probably find a job as a Hollywood script writer.

Which brings up the difficult question, how much of history is truth?

Has much of it been written, as one skeptic has accused, by the winners of wars or of succeeding civilizations and cultures? The first Europeans to come to B.C. all but dismissed native history—that's what they meant by legends—because it’s oral. Does writing it down guarantee authenticity?

Psychological research has shown that several people witnessing the same traumatic event, say a bank robbery, will often give varying, even conflicting, descriptions of the robber. Most will agree on general points but vary greatly on others. Who’s right?

So, how do I research the Chronicles and who do I trust? Can you trust me?

Sources vary, of course. My personal archives and library, begun at age 14, has grown exponentially over the years. I began by reading other writers such as B.A. McKelvie, Cecil Clark and several others who specialized in provincial history. I did what they did by visiting the B.C. Archives and the public library, spending countless hours hunched in front of microfilm machines before moving up to interviewing actual participants of, or witnesses to, historic events, and reading almost everything I could on B.C.

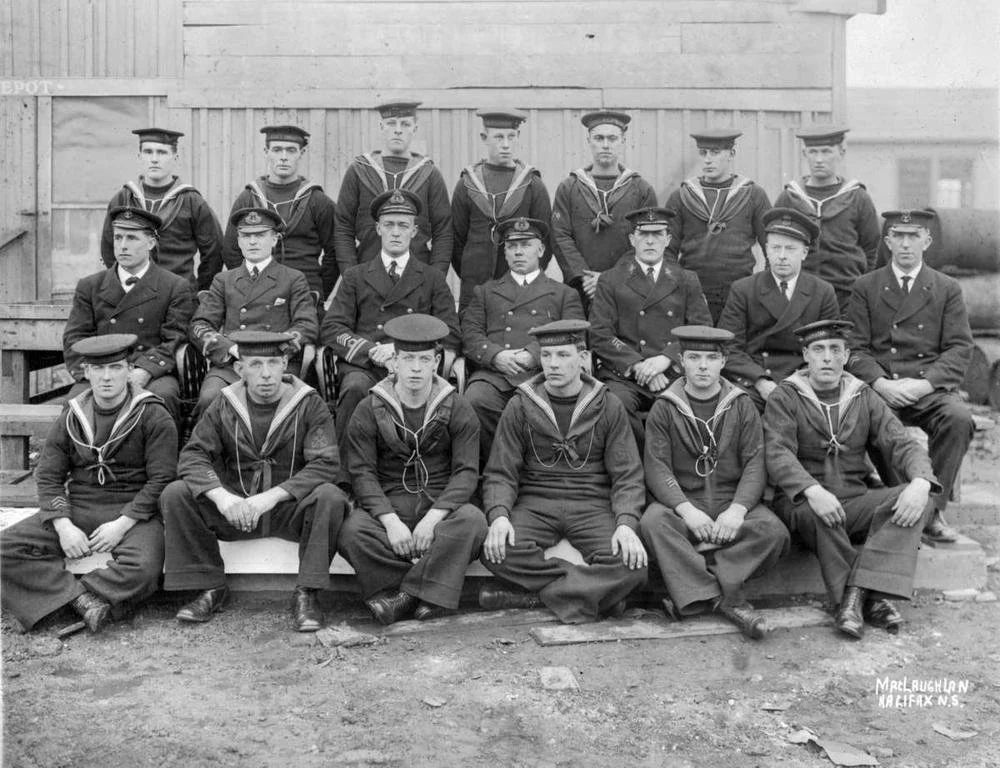

These men risked their lives for Canada. If we’re going to remember them, we owe it to remember them factually. — BC Archives

We're fortunate, you know; as hundreds, probably thousands, of books that we term 'regional history,' many of them one-shots by authors whose names you don't recognize but whose credentials are 24-carat, are available to researchers who know how to seek them out. (Today's internet makes it that much easier in some cases.)

One of my best-ever sources over the years has been the Annual Reports published since 1874 by the British Columbia Department of Mines.

Up until the 1950s they were a priceless treasure trove of information, much of it detailed and in the very words of the regional mining inspectors.

One in particular stands out for me. An inspector investigating a coal mine disaster in the Similkameen in the 1930s was describing the effects of the explosion and the unsuccessful attempts to rescue more than 30 trapped miners. Remarkably, he’d been on the site (on the surface, fortunately for him) when explosion ripped through the underground workings.

Horses, pit ponies and mules, heaven help them were essential to mining throughout BC. How could white mules stay clean in a coal mine? — BC Archives courtesy of Eric Brighton.

Thus his report, although written with the knowledge that it was to be filed with his superiors and ultimately published for posterity, has an immediacy that is neither clinical nor matter-of-fact.

There, in the midst of his report—and as tightly abbreviated as it is, his conflict of professional reserve and his personal sense of shock at what he had witnessed and of the even greater horrors that followed, ring out loud and clear—is a most unusual observation. Almost in mid-paragraph, he addresses an issue that had intrigued him for years.

It was just a little thing.

How was it possible, he marvelled, that white mules working underground never got dirty, whereas miners returned topside as black as the coal they mined?

Perhaps as remarkable is, how did this nebulous query so innocently and so incongruously expressed by a man who’d seen tragedy in the collieries before, although always after the immediate fact, make it past an editor? No amount of research on my part could answer that question—I'm just glad that the anonymous editor let it pass.

But I've strayed somewhat from my ramble on veracity.

No one would question the mine inspector's credibility and his example helps to make the point that firsthand sources are always highly desirable. But referring exclusively to one person's version of what happened is like examining something through a microscope; to get a clearer picture we generally must look at it from a greater distance and from other angles. Human memory, after all, isn’t infallible even when it's untainted by personal biases and egocentric viewpoints.

Sometimes, when all is said and done and a researcher ends up with several versions, he or she splits the difference.

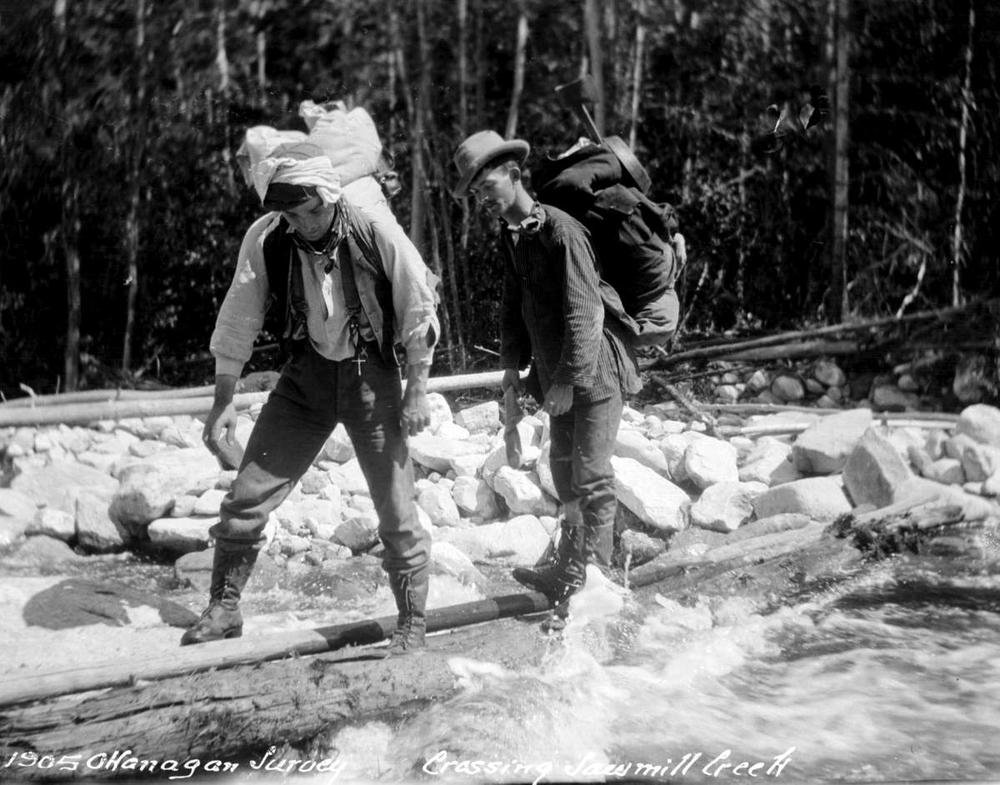

What stories these men could tell! How sad that so few of their stories have survived. — BC Archives

Sometimes one has to draw one's own conclusions as to what really did happen. This can be an arbitrary judgment of a particular source, or instinct honed on experience. One thing is certain: never, never trust to memory if it's a critical fact. (And, unless there's valid reason not to be, try to be objective.)

I've never forgotten the day that, young and impressionable, I complimented one of my favourite historical writers with the remark that he must have a fantastic file system. With the self-satisfied smile of a senior statesman, he pointed to his file system—his forehead. I was impressed!

Until years later when I found myself following in his footsteps and researching some of the same events.

Problem was, my version didn't always match his on some of the critical facts. What divine source of information did he have that I didn't? I agonized. Then it struck me. I was trusting to the written records before me. He was drawing from his 'files'.