Thomas H. Murphy, Miner and Adventurer

It was a colourful career that Thomas Herbert Murphy reflected upon in the summer of 1930. A lifetime that had been seen him in the mixed roles of sailor, blackbirder, prospector and Justice of the Peace.

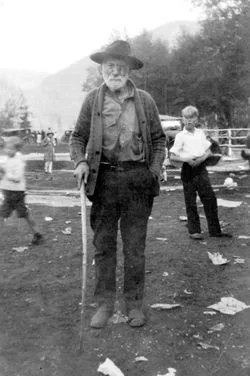

Looking every inch the old prospector, Thomas Murphy, —findagrave.com

Nova Scotia-born, he’d followed the will-o-wisp of adventure to the West Indies, Europe, China, the South Seas, New England, New Zealand, Australia, the United States and—finally—British Columbia.

As a seaman before the mast, Murphy had known the great tea clippers. However, upon reaching Australia, he’d been bitten by the gold bug. —www.publicdomainpictures.net

“Once into mining you could not turn me to anything else,".he said. Like legions before and since, Murphy was addicted to Dame Fortune and he spent the rest of his life in search of El Dorado.

Many years later, he told an interviewer, “I did pretty well at it but, like every successful miner, I put most of what I made back into the ground looking for more and lost it. That's what makes them say that every dollar taken out of the ground cost a dollar: one man gets $50,000 or $100,000 out of his mine on which he has spent, say, $10,000; another puts $50,000 or 100,000 into prospects and mines and takes $10,000 out.”

The following account of some of his mining adventures in British Columbia, principally in the Similkameen, has been edited from those reminisces.

* * * * *

I am an old gold mining hand, have tried it in Australia, New Zealand, the western States and British Columbia. There is not much about the game that I don't know but I have never made any great fortune out of it. There are few prospectors who do.

Well, I've had a good life of it; I don't know that I'd want to live it any different if I had any chance at it again. Maybe I'd have a fortune, though, if I did for I would know where I made a bad guess. No living in the city, though; if I made a pile there is nothing there to equal life out on the hills.

With a comfortable shack to keep the winter weather off your head, and a good old prospector friend or two to come in and have a crack about mining and the good old times when some of the camps you have known were going good...

I got lots of time now for I'm not as spry as I used to be and can't move about the hills as I used to do. My eyes bother me some but I can tell indications of mineral as well as ever I could.

I came here to British Columbia (early in 1886) at the time of [the] placer gold excitement on Granite Creek. Granite Creek was a nice creek, too; quite a bit of gold on it, and I like the country, too. I have been here ever since. I expect to stay here, too. I came up from the United States on a steamer to Portland, and from there to Vancouver, and then by trail from Hope...to Otter Flat and down the Tulameen [River] to Granite Creek.

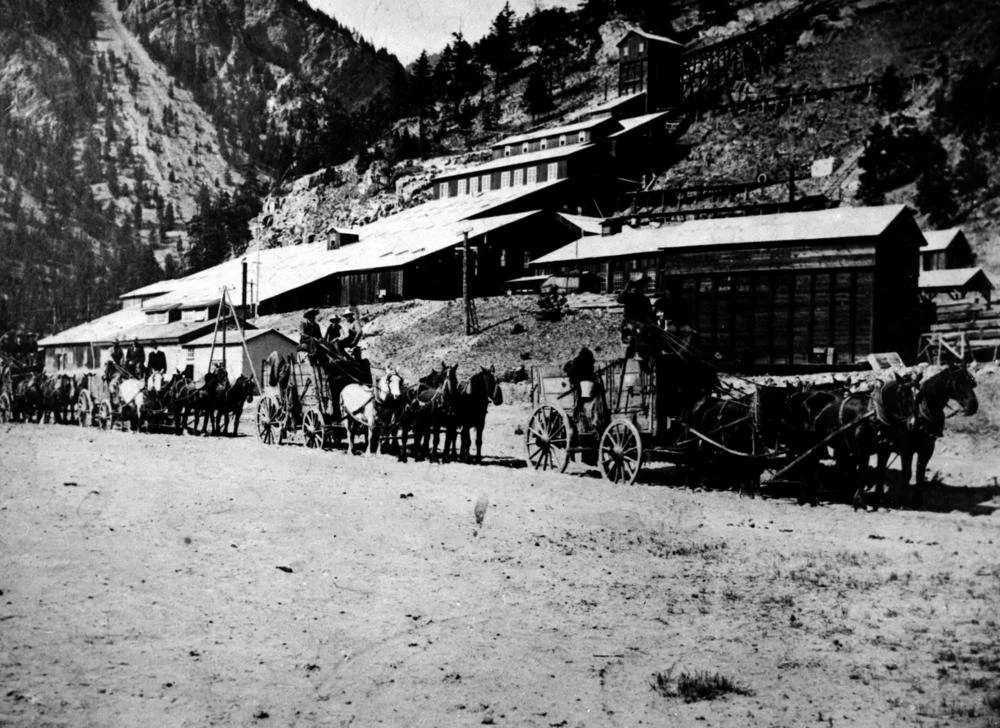

Granite City, so-called, 1888-, where Thomas Murphy worked his hydraulic claims. —BCA

Being early in the spring there was a lot of snow still on the trail and travelling wasn't any too easy. There were 100s of men pouring into the creek and the other creeks in the district.

This young chap is panning for gold in the Tulameen River for fun—for Tom Murphy and other miners of his day, gold mining was serious business. —BC Archives

Gold was nothing new here, for Chinese had been mining on the Tulameen since 1860 or thereabout[s], and whites, too, but until Johnny Chance found gold on Granite Creek that day the white miners had not made any attempt to try it out. I wonder [that] Johnny ever made the discovery; if ever there was a lazy fellow it was him. it was his very laziness and easy-going way that led to his seeing ‘colour’ in a pool he was bending over...

By the time I got there all the promising ground had been staked and I had to buy...two or three [claims] on the creek.

This is an 1890s gold dredging operation on Granite Creek; it’s unlikely that Murphy’s dredging claims were as large. —BC Archives

When I came Bob Stephenson was the principal operator on the creek and he remained so throughout its history. He was one of the finest men who ever mined in British Columbia, and was popular everywhere/ He generally had a black horse, and Bob and his mighty black horse, which was the way he used to refer to it, were known in every part of the province, I think. There was no place in the Lower Mainland and Boundary Country, at any rate, that he was not a familiar figure in.

He and I were the two who remained longest on Granite Creek and displayed most faith in it. Bob had disposed of his interests to a Montreal Syndicate and was mining manager of it, spending most of his time on the creek. I forget whether or not he was president of the company.

My most promising claim was what we called the Pogue Hydraulic Claim, which we tunnelled and worked as long as it yielded any gold.

A closer view of a Granite Creek gold dredge, this one from the 1920s. —BC Archives

My partner in it was at first a man named Kyle and later on a man named Newton. There were so many men on the creeks here that I forget most of them. They came and went a lot, anyway... Perhaps none of [them] made any fortune out of Granite Creek but we lived anyway and had a good time

Granite [City] was a one-street town. It was down at the mouth of the creek on the left bank, and had just the one narrow street of log buildings. The big population of miners lived mostly in town at first and then in cabins up the creeks or close to their claims. There were three general stores in the town, F.P. Cook’s, Mark Woodward's, and J. H. Duncan & Co.’s, which really was a branch of Howse’s store at Nicola and was run by Charlie Reveley.

The ground the Granite Creek Hotel was kept by Mrs. Alice James and Dan McKay had a hotel. The hotels were a storey-and-a-half affairs, the upstairs being what they call here a ram pasture, one large room in which anyone is welcome to shake-down in his own blanket...

Granite Creek was a little frontier town when I first saw it, just one street of log cabins... We had three general stores on the creek at the outset and another one or two started up afterwards, but one by one they all got out. F.P. Cook’s was the last to go, and then we had to go into Princeton to his store there or Howse’s.

It would make you laugh, their idea of business in some of the stores. They were never in a hurry, but, of course, the customers were not in a hurry either. If trade was not very brisk the merchant might as likely as not be down at the hotel at a game of billiards or cards or having a drink, and you had to go and find him, And that generally meant that you had to have a drink or maybe two or three of them before you started back to the store.

They charged pretty steep prices...

After the stores closed in Granite Creek miners had to go to Princeton to do their shopping. As Gibson’s Hardware promised in their signage, they “sold the goods”. —BC Archives

As the town developed and traffic increased the government were wanted by us to build a road. We had only a horse trail all the way from Princeton in the one direction to about 16 miles above us in the other. There was a road of sort[s] from Spences Bridge as far as Jack Thynne’s ranch, but from there south there was only a trail.....

Anyway, we thought that as the government was getting a good deal of revenue out of our development of Granite Creek Camp and the province was getting the advertising, they might at least make it easier for us to get stuff in and out.

I was always the man picked on in this section of the country to go to Victoria to get roads, bridges, trails and school-houses, and it is a strange thing that I always had to do it on my own, strictly my own time and my own money, every time. However, it was all for the good of the district...

The petition we made to the government... was reasonable and we got what we wanted...

I was often in Victoria on deputations for one thing or another and I was always called on to speak. I was chairman of the public meeting held in Princeton to advocate the payment of a bonus to the V V & E. [Victoria, Vancouver and Eastern Railway] to get them to come through the valley, and I was one of the members of the deputation that went from the valley to urge that policy upon the Dunsmuir government...

Murphy and his fellow miners wanted a railway but it was years before their dream came through. —BC Archives

told them down there [in Victoria] that the CPR had the dry-rot, too, and that if they did not do something to give us competition and railway service [in the Similkameen] I would begin to think that the dry-rot had attacked Victoria and the Dunsmuir government, too...

I have been a Justice of the Peace for 25 years, and I was a member of the board of licensing commissioners frequently for Similkameen and Nicola when bar licenses were enforced...

British Columbia is a great province and has always come to the front. No one really knows what is in it in the way of minerals. The future will show mines the equal of any there have been for there is only a small part of the country that has really been thoroughly prospected. I have always tried to keep the mining industry to the front and never lost a chance to say what I thought about it and I have encouraged all the capital I could to invest here...

There is no doubt that in periods of prosperity the miners and prospectors of earlier days were reckless and prodigal, but they had generous dispositions which never failed to respond to appeals for assistance, or to relieve the distressed and unfortunate. The lives of all those man are clearly associated with the early history of this country, on which they have left an impression so deep that future years cannot obliterate it.

They were always noted for self-reliance, rugged endurance and sterling worth.

The probability of the discovery of rich placer camps even yet is the star that keeps leading the prospector on into the most remote and inaccessible places, and through hardships and privations which does not kill privation which does not kill nor diminish their hopes...

Similkameen mining dates back to 1860, when both whites and Chinese were busily engaged pioneering on the Similkameen and Tulameen and all their tributary creeks. That was partly the reason Governor Douglas sent J.F. Allison in here to investigate what was being done and report to him.

Old Allison mined the first copper around here.

Without roads or railways, prospectors and miners did what they had to do—even packing the ore out on their backs as W.K. Rodgers is doing at the start of what became the fabulous Hedley Mine. —BC Archives

He worked the mine for a short time and a shipment of ore was sent out over the Hope Trail by pack-train bound for San Francisco. The smelter report from there was very good; it gave 37% copper; but the expense was too great at that time to make it profitable, and so nothing was done about it and everyone forgot all about copper. Indications of other metals were found in all gold mining in the province nearly, and an old man thought about a time when these would be recovered, but in those times gold was the only thing anyone wanted or cared about....

There were a lot of mining camps in this district... I do not believe I can remember them all now after 30 or 35 years... This Boundary Country is full of townsites that never were and old mining camps that were but are no longer.

The quick rise in the price of copper drew many prospectors here by the summer 1898, and a number of claims were staked on Copper and Kennedy mountains. There was a big rush in 1899... In 1886 some of the claims on Granite Creek made a yield of 30 to 50 ounces of gold a week. Of course, there were all the other creeks in the district being worked, too, but...Granite Creek, being the largest, and some of the others being tributaries to it, gave its name to the camp...

Wherever gold is found there are base metals. Everyone knew there was copper to be found in the Similkameen but, until the 1890s, without railways and smelters, it was too expensive to develop. Then came the big players like the Hedley Mine, to name one. —BC Archives

Much gold was taken out the first year from Granite, Slate, Bear and Collins creeks; well on to half a million dollars, it was estimated, when you consider what got out without being reported. From Granite Creek there was nearly $50,000 reported, and the gold commissioner’s estimate was that there must have been $90,000 taken out. [Official figures for Granite Creek are considerably higher than Murphy's.—TW.]

The gold was coarse, with one or two nice nuggets being found frequently and larger ones occasionally.

In 1886 two were got from Bear Creek, one of which was worth $400 and the other $415. A Chinaman [sic] working for a company on Boulder Creek found one in 1887 worth $900. It was exhibited by Wells-Fargo [sic] in their windows in Victoria that winter.

Placer claims yielded from $5 to $30 a day to the hand. A young chap from London paid his last dollar to record a claim, borrowed a rocker, and the first afternoon took out $400. He left the creek with about $11,000.

I remember that on Discovery claim over $800 was taken out in one day's washing. A little below that Adam Faye had a fraction which he worked with a rocker, banking his dirt in the forenoon and washing in the afternoon. When the sun shone on that bank the gold could be seen, glittering like sparks...

In 1900 I was working in my tunnel with Johnny Amberti when the entire bank caved in and buried me up to the neck in mud and wash. I tell you, it was a pretty narrow shave I had [almost being] covered up altogether. If I had [been covered] up, no doubt I would have been smothered to death.

I managed to keep my mouth clear of the debris that was tumbling down, and gave Johnny directions how to go to work to dig me out. It took him two hours’ hard work to get me clear.

The stuff kept flowing and falling in as he dug, and when you see how tall I am you will know he had a long way to dig down. I'm a bit stooped now but in my prime I was a good height. I was pretty badly crushed and had some ribs broken. Caving banks are always a dread of miners and a man does not like working where there is any danger without a partner near. If he is by himself in such a case he goes at it very carefully, for many a man has got caught as I was and lost his life for lack of help.

Granite City in 1980; there’s even less to see today. —BC Archives

Johnny Amberti was a fine old fellow and none better in the game, and had been all over the world, you may say, in mining camps... He was an expert prospector and miner and a good companion...

The winter of 1886-87 was a very bad one. It was as cold as 38[F] below zero and there were three feet of snow on the ground in many places. Horses were dying for lack of feed, hay being scarce and the deep snow making it impossible for them to get any grass. It was a good deal of hardship, although there was no lack of food nor fuel, but there were some men who had not saved anything to tide them over a long spell of enforced idleness.

I remember that winter a miner known as Poker George got his feet frozen badly out on the hills and he died in a few days from gangrene.

* * * * *

Thomas Herbert Murray had been in the Similkameen for 44 years at the time of his interview at Tulameen. He was a typical minor of his generation—a breed of man who did much to make British Columbia what it is today.