Editorially speaking…

Further to today’s feature article on engineer extraordinaire Andrew Onderdonk, an attempt to answer: Hero or Heel?

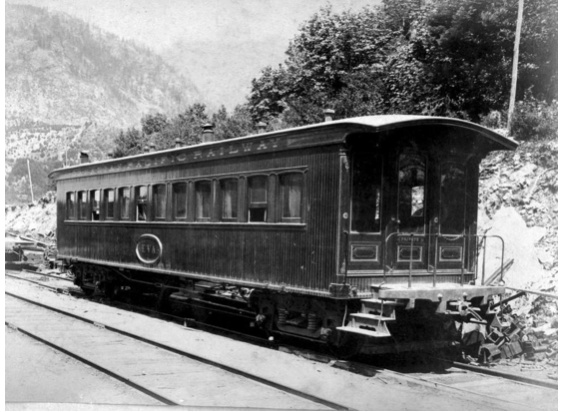

As the man in charge of all aspects of construction, Onderdonk had to move up and down the line—in comfort, obviously. We can only wonder what his labouring navvies thought of this miniature palace on wheels. —BC Archives

It has been estimated that Andrew Onderdonk’s “army” numbered as many as 9000 labourers of various nations, mostly White, including 2000 Chinese. As can be imagined, the logistics of managing and maintaining such a large and multinational workforce scattered along 100s of miles of grade, would have been incredible.

According to renowned CPR engineer H.J. Cambie: “Mr. Onderdonk supplied excellent camps and good sleeping quarters and the food in his camps was really of good quality and well served... [He] had a lot of very fine superintendents who pushed the work along as fast as it was possible to do.”

How much personal oversight was Onderdonk able to give to his workers? In the political arena, premiers and ministers sometimes fall on their own swords by taking responsibility for the failures of their subordinates. Ship captains are held responsible for all that befalls their vessels.

An estimated 600 Chinese died during construction of the Fraser Canyon section of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway. Was Andrew Onderdonk morally liable for the deaths and injuries incurred in the course of the construction that he contracted for in B.C.?

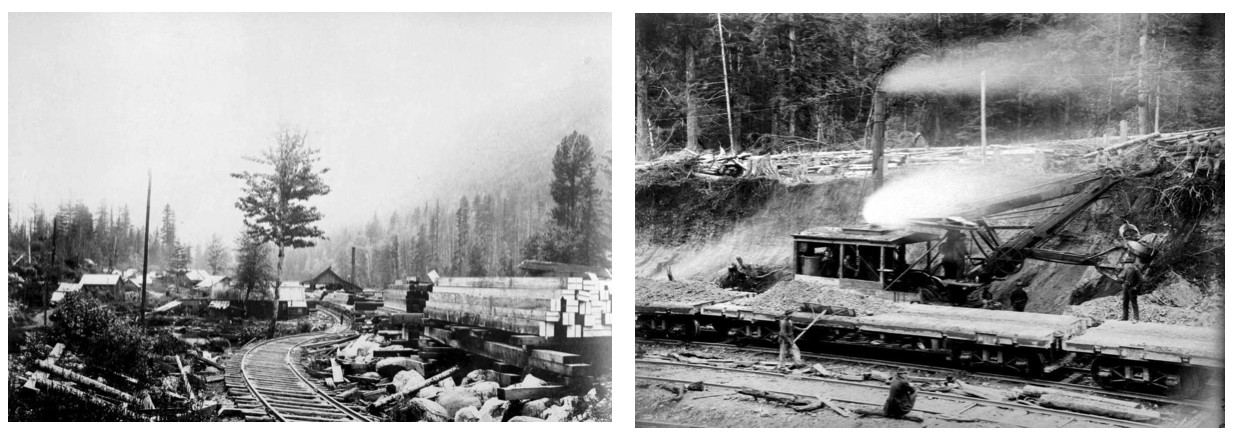

Building a railway required dozens of skills, including the sawmill, left, a machine shop and, right, use of an early steam shovel. —BC Archives

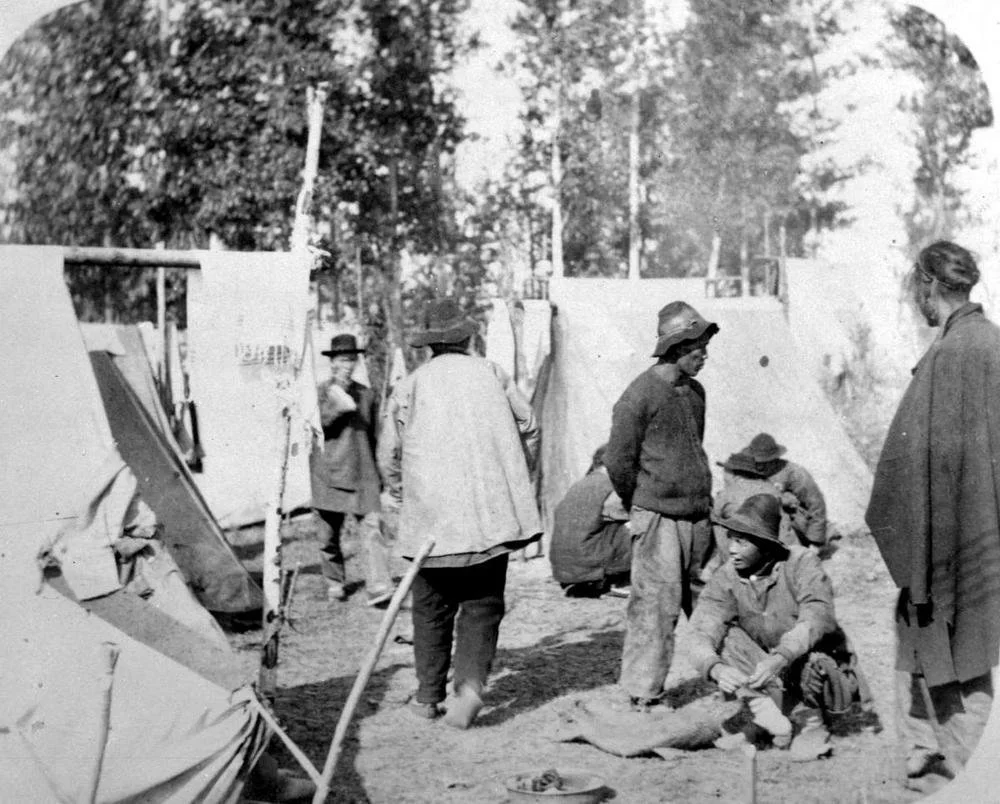

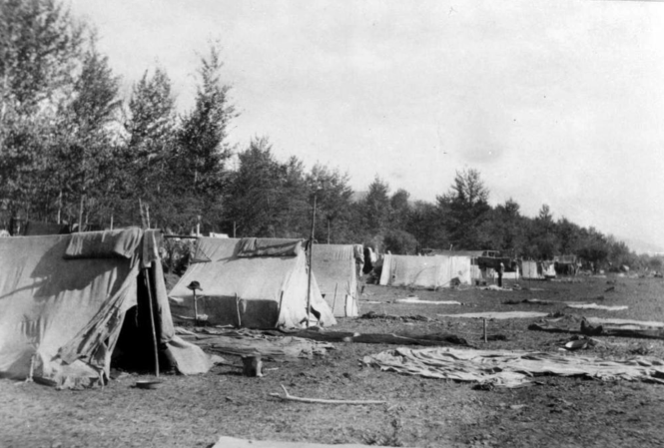

Chinese labourers were recruited by Chinese subcontractors who saw to their travel expenses, meals and, once on the job, to their general welfare. We’ve seen that Onderdonk was praised (likely by White employees besides engineer Cambie) for his generous living accommodations and food allowance—yet some Chinese workers, all of whom lived apart in tents or shacks of their own making, were known to have died of scurvy for want of fresh produce.

The overall accident rate under his watch is, by today’s standards, appalling: 600 deaths. How many more were maimed?

Yet workers seem to have accepted these known risks. Were they that desperate or, perhaps, fatalistic? It’s a matter of record that it was almost common practice for construction workers to treat volatile dynamite so casually as to invite disaster. In winter, for example, men heated it to operating temperature over their breakfast fires, often with lethal results.

How high up the chain of responsibility do we go? To Parliament and those whose political lives were on the line if the railway wasn’t finished as promised?

Originally, in keeping with the temper of the times [there’s no escaping the fact that B.C. was virulently anti-Chinese], Onderdonk had promised to use only White labour and “only with reluctance engage Indians and Chinese”. His desperate need of workers, as we’ve seen, forced him to spread his net, first by hiring experienced Chinese navvies from across Canada and the U.S., then, through a subcontractor, the Lian Chang Co., directly from China.

Over three years, 1881-1884, this firm imported 10,000 labourers direct from China for construction of the CPR across Canada, for a total of 17,000 Asian workers who, even then, were outnumbered by Whites.

Unlike White labourers, Chinese navvies had to provide their own accommodations. —BC Archives

The Asian Heritage Society of New Brunswick (www.ahsnb.org), for one, states: “Chinese were often assigned the most dangerous tasks. White workers were paid $1.50 to $2.50 per day and had their camp and cooking gear supplied; Chinese workers, paid $1.00 per day, were compelled to purchase their own supplies...”

To blasting and tunnelling deaths and injuries, the AHSNB adds deaths by exhaustion and exposure (while travelling between camps and worksites), and further charges that the higher accident rates for Chinese workers were “excluded from official company reports”. Their resulting resentment is cited as having led to a violent outbreak between White and Asian workers in 1883 that resulted in at least two deaths.

This Chinese camp would have been even more miserable in winter. —BC Archives

Other charges against the treatment of Chinese workers include inadequate medical care, poor living conditions and food: “Scurvy became chronic because low wages forced Chinese workers to subsist on a diet of rice and ground salmon without fruits or vegetables....”

As confirmation, the AHSNB quotes an editorial in the Yale Sentinel which referred to Chinese workers as “fast disappearing under the ground” for lack of medical attention and for want of any concern by the Chinese subcontractor “for these poor creatures”.

As for Andrew Onderdonk, according to the editor of the Sentinel, he “declines interfering...”

On that note, I must leave this for today. Onderdonk’s abilities as an engineer can’t be disputed. He couldn’t possibly have been ignorant of the deaths of 100s of Chinese workers. Did meeting his contractual commitments overpower any sense of humanity on his part? Did he blind himself to the misery that accompanied construction through the treacherous Fraser Canyon? Or—?

It would take intensive research of Onderdonk’s business memos and personal papers, and the mountains of records that document construction of this stretch of the ‘National Dream,’ to even partially answer the question: Was he a good man or callous to the point of being a monster?

Perhaps the truth lies somewhere between. But, damn, he was a marvellous engineer.