He tamed mountain of horror – but at what cost?

Fame can be a fleeting thing—today’s “celebrity,” tomorrow’s nonentity. It can get worse than that—yesterday’s hero, today’s heel!

Even though he has a British Columbia mountain named for him, if you google Andrew Onderdonk, he gets little mention beyond the first two listings of several pages of other Onderdonks which include members of his own family, and doctors and lawyers, etc.

Andrew Onderdonk. —Vancouver City Archives

There’s no denying that time not only passes—but times change. Once celebrated for his building of much of the Canadian Pacific Railway through the Fraser Canyon, there’s no denying Onderdonk’s engineering abilities or his strength of character even a full century and a-half later.

What has come under the glass in latter years is his treatment of the army of Chinese labourers he imported to blast his way through the mountains.

I didn’t look beyond his accomplishments when I first wrote about this engineer extraordinaire, years ago. But I’ve dug a little deeper this time around...

* * * * *

If ever British Columbia has known the right man for the job, that giant was Andrew Onderdonk, unsung hero of the rails.

He built a railway where few—man or beast—dared to set foot, through Fraser River’s precipitous canyons and, in so doing, wrote a unique chapter in provincial marine lore.

This apparent anomaly dates back to March 1880 when the building Canadian Pacific Railway faced seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Beset by financial crises, political scandal, unbelievable construction difficulties and the impatient clamouring of British Columbia, the Transcontinental had fallen far behind schedule and faced complete halt.

William Van Horne, the driving force behind construction of rails across Canada. —Wikipedia

One of the more formidable problems facing Harry director William Van Horne was just a tiny line drawn upon a map. On paper, this final link in the continental chain looked anything but complicated. In reality, it was an engineering nightmare.

Between Port Moody and Savona Ferry, at Kamloops, lay some of the grimmest terrain ever challenged by human Ingenuity. Through the rocky fortresses of Fraser River, the Coast Mountain Range and the Thompson River, 213 miles of track had to be laid.

Incredibly, these obstacles didn’t daunt a 32-year-old engineer from New York. Andrew Onderdonk, a direct descendant of one of the first Dutch families to settle in America, didn’t hesitate to attempt the seemingly impossible. He’d graduated from the Troy Institute of Technology with honours then supervised the construction of several vast projects throughout the U.S., including the building of ferry slips and a mammoth seawall in San Francisco.

With these under his belt, and with liberal backing from friendly financiers, he agreed to take on the multi-million dollar contract for the controversial Port Moody-Kamloops section and calmly went to work.

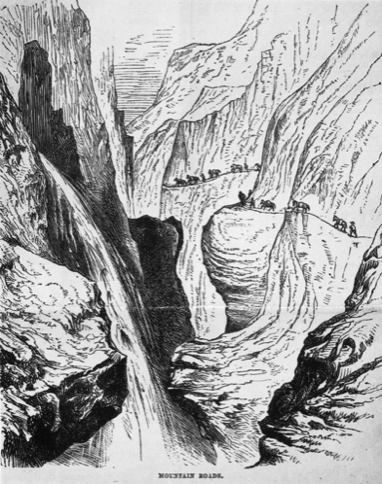

Twenty years before Onderdonk, the Royal Engineers had accomplished an engineering wonder of their own, the famous Cariboo Wagon Road. —BC Archives

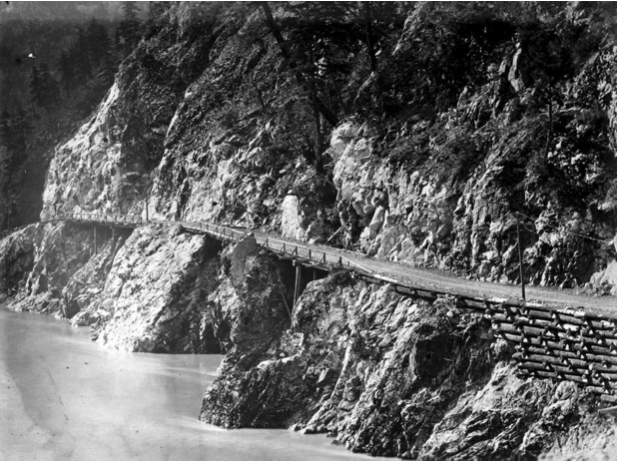

On horseback, he inspected the notorious Canyon by following a precarious goat track blasted from solid rock high above the boiling river. In places, frail wooden bridges seemed to hang over eternity, supported by invisible supports. Using dynamite, his men would have to gouge a railway along the canyon’s very edge. Where 1000-foot cliffs barred the way, men with explosives would have to be lowered by ropes to drill and set their charges.

An artist’s conception of horses packing freight on the “road” to Cariboo. Andrew Onderdonk was supposed to build a railway through these same mountainous canyons. —BC Archives

With Yale as his headquarters, Onderdonk began by constructing a hospital which he realized would be sorely needed, and established work camps with generous cooking and boarding facilities. Years after, some former employees would hail him as "the best boss we ever had".

Upriver, he built a dynamite plant capable of producing 1200 pounds of explosives per day, then faced his first real obstacle, a shortage of labour. Manpower was at a premium in B.C., and despite the attractive offer of $2 a day and all found, Onderdonk couldn't recruit a sufficient force. In typical manner, the engineer’s answer was nothing less than a continental advertising program. Within months, a rag-tag army of inexperienced labour formed at San Francisco and was ferried north to the Fraser River.

Labourers, farm boys, adventurers, misfits and thieves, they undertook to tame a mountain horror.

Another view of the terrain that both road and railway engineers faced in taming the Fraser Canyon. —BC Archives

On the morning of May 14, 1880, the first blast was detonated. with a mighty roar that echoed throughout the canyons and started a thunderstorm. The vast project was begun.

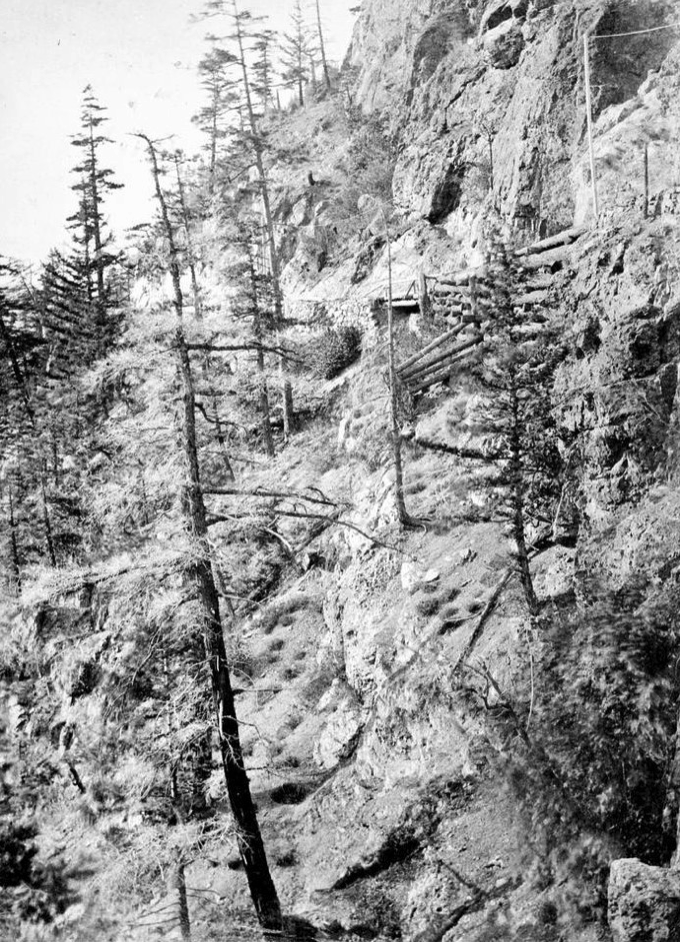

Look closely. Can you see the road? And, remember, trains don’t climb hills, they need almost level ground. Somehow, Onderdonk and his army of labourers bulled their way through the Fraser Canyon. When they couldn’t go around, they went through in a series of tunnels, one of them 1000 feet long. —BC Archives

“It was difficult to get men willing to drill and blast, suspended by ropes over the chasm walls," wrote Ian Macdonald. "Slides kept hampering the work, and the road below, lifeline to the interior, had to be kept clear. Accidents kept mounting, attended by difficulty in conveying the injured down to Yale, where Mrs. Onderdonk, a capable and unpretentious woman, did a big job in superintending the hospital and being hostess to visiting dignitaries."

“The blasting which continually reverberated along the canyon, caused a lot of rainfall. In spots the work cost $300,000 a mile, with the Macdonald government in Ottawa hard-pressed to raise the funds."

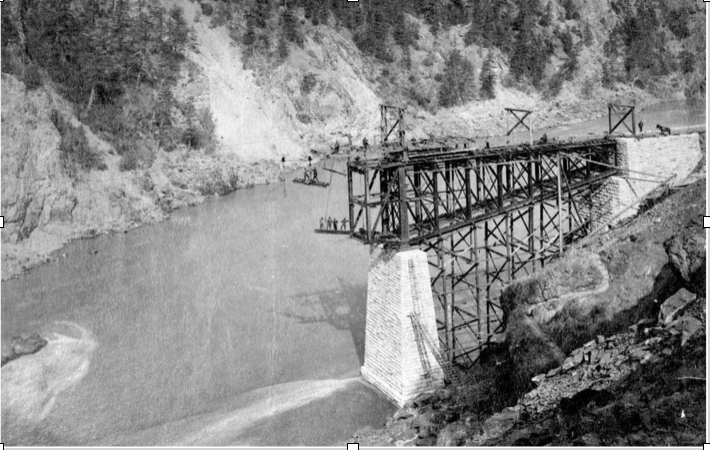

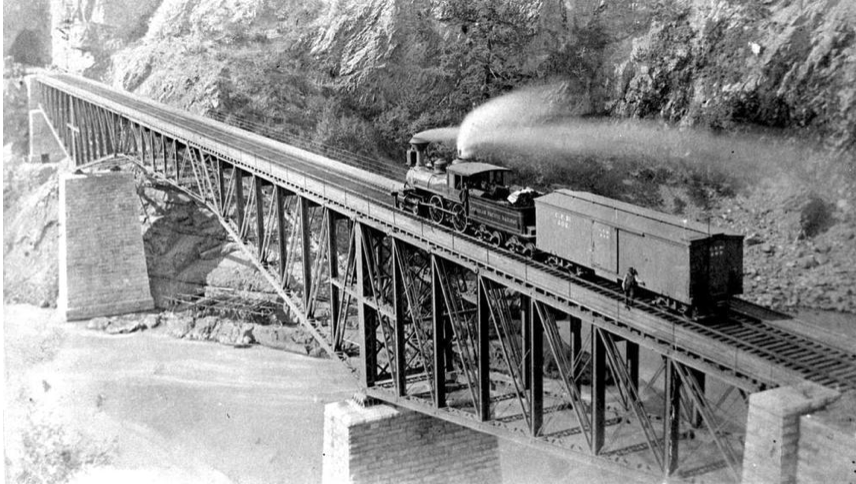

Bridges had to be built, too, this one of pioneering cantilever design at Cisco Flat near Lytton. —BC Archives

The finished product. Marvellous! —BC Archives

Despite constant complaints from a worried Ottawa, Onderdonk forged ahead. But he was already losing his race against time. By summer, he realized he could proceed no farther without 1000s of additional workers.

In desperation, he informed the federal government of his intention to import 2000 Chinese coolies. Without waiting for a reply, he put his plan into action by chartering two steamers to rush Chinese labourers to British Columbia. Their sudden arrival took the province by storm, arousing vehement public outcry.

Importation of the industrious Chinese would for years to come be a bitter issue and ignite violence more than once. Onderdonk, the hard-headed contractor, acted with his usual daring. Once again, his gamble paid off.

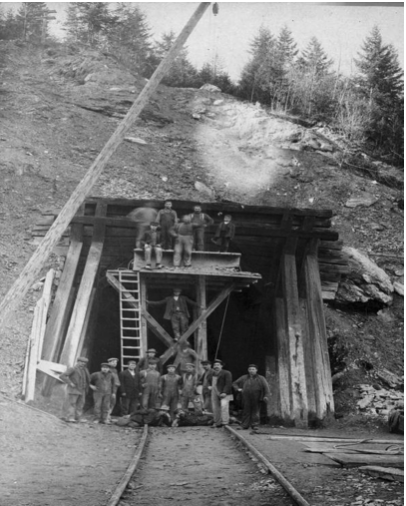

This CPR crew is lining a tunnel. Onderdonk’s men drove 16 in all. —BC Archives

It was then he faced the problem which was to make history. Hindered by the exorbitant tolls ($10 a ton) on materials freighted over the Cariboo Road, he determined to send a steamboat to Boston Bar. The fact this manoeuvre meant navigating Hell's Gate Canyon, the worst stretch of whitewater on the Fraser River, meant little to the engineer.

“You're crazy!” cried veterans of the Pacific Northwest swiftwater fraternity upon the announcement of Onderdonk’s plan. All agreed that it was impossible—all but Onderdonk and, early on May 4, 1882 Sarah Onderdonk formally christened her husband's 127-foot sternwheeler Skuzzy at the little settlement of Spuzzum.

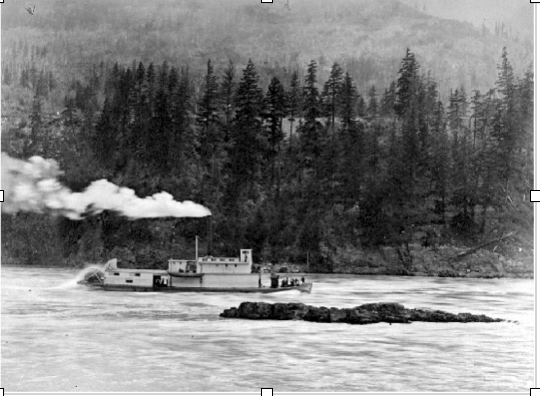

The S.S. Skuzzy at work. To borrow from Admiral Farragut, taking on Hell’s Gate was “Damn the [rapids] full speed ahead!” —Wikipedia

Minutes later, the 254-ton craft named after a nearby stream was launched into the Fraser. Some ridiculed Onderdonk, many pleaded with him to change his mind, warning that the Skuzzy would be lost. But he wasn't to be swayed.

He’d already found the man to tackle the raging waters of Hell's Gate, Capt. Nat Lane Jr. Even his detractors agreed he’d made the right choice. However, when Lane saw the maelstrom of rapid and rock that was Hell's Gate, he promptly returned to the lesser hazards of the Stilkine River. When finally Onderdonk turned to Capt. Asbury Insley, the unnerving dangers facing the Skuzzy had increased immeasurably.

From high in the mountains, melting snows poured millions of gallons of water into the swelling Fraser. Within days the river was a ravaging monster, overflowing its banks and flooding thousands of acres. On May 17, the day of the immortal contest, the Fraser roared at its highest level in 40 years.

Viewed from on high, the incredible surge of Hell’s Gate doesn’t show its full force. Today, visitors can cross by air tram, a foot bridge or navigate the rapids in professionally guided inflatable rafts. Onderdonk’s steamboat Skuzzy, it should be remembered, was trying to fight its way upstream.—D. Harvey photo, Wikipedia

Undaunted, Capt. Insley, acknowledged as the best best Fraser River pilot of his day, swung Skuzzy’s spoon-like bill into the surging current. Tall funnel belching black smoke, the steamer charged upstream, an angry white froth sweeping past her bluff nose. Again and again, Insley forced his bucking command to the attack, exhausting his vast store of experience, trying every trick he’d ever learned or heard of.

But it was no use. Hell's Gate had beaten them.

But if Onderdonk was disappointed, he didn't let it show. Rumours swept the Northwest that he’d given up, that the Skuzzy would be dismantled and shipped overland. Weeks later, Onderdonk quietly announced it was Boston Bar or bust—through Hell’s Gate.

In the meantime, he’d replaced Insley with three Columbia River veterans. From Lewiston, Idaho came the brothers, Captains David and S.R. Smith, the first man to navigate the treacherous Shoshone River through the Blue Mountains, accompanied by Capt. W.H. Patterson and engineer J.W. Burse. On the eventful day of Sept. 7, 1882, 100s of eager spectators lined the rugged river banks to watch the David-Goliath struggle.

News of the one-sided duel had excited mariners and landlubbers alike, and bets were placed from Spuzzum to Seattle. Few backed the Skuzzy.

To the cheers of those on shore, Capt. Smith forged into battle. Boiler almost bursting, paddles thrashing the rapids frantically, Skuzzy inched ahead. The little steamer bucked as in terror, her bow plunging beneath the foaming current time and again. In the wheelhouse, Smith and Patterson fought her wildly spinning helm and shouted orders to the 17-man crew.

Hours passed, Skuzzy gaining ever so slowly. The first day was followed by a second. Still, the straining steamer moved forward. Three days. Four. By then, the exhausted crew realized that they’d made little headway. Worse, it was becoming increasingly apparent that they couldn't maintain the agonizing battle much longer. Soon, they'd be spent and the triumphant Fraser would hurl Skuzzy downstream.

And so she would have been but for the Smiths’ and Onderdonk’s 11th hour inspiration: 150 Chinese workers placed at strategic points along the canyon rim. Heavy ring bolts had been hastily driven into solid rock, through which were passed stout hawsers secured to Skuzzy’s capstan and steam winch.

As Skuzzy’s puny 30-horsepower engine thumped loudly above the thundering roar of the river, the shore gangs heaved on the lines and 15 crewmen worked her capstan, pitting muscle against the might of the Fraser. Inching along the cliffs where a false step meant instant death, the Chinese pulled with every ounce of their strength.

Once, twice, they strained at the ropes, the steamer seeming to be held fast in the rapids’ grip. Then—Skuzzy moved ahead. One foot, two... over the infamous China Ripple, she struggled. Finally, after a week of inhuman struggle, she was above Hell's Gate. With her crew slumped in exhaustion and her hull scraped and gouged, Skuzzy rested.

Andrew Onderdonk, the mad genius of the CPR, had won again. His remarkable achievement was hailed the length of the West Coast and across Canada, one and all praising his determination and the courage of his river men.

Skuzzy still faced more than 20 miles of rough water and rock before she reached Boston Bar but the battered lady limped into town without further incident. The Smiths then braved the current once more, battling their way to Lytton after a further white-knuckled 20 miles. After returning to Boston Bar, Skuzzy enjoyed a well-earned rest made necessary by a large rip in her side.

Her 20 watertight compartments, an innovation in ship design, had kept her from sinking.

Repaired, she began regular service between Boston Bar and Lytton with vital supplies under command of Capt. James Wilson. Ironically, Skuzzy had beaten Hell's Gate but she couldn't withstand the daily hammering of a raging river and continual collisions with submerged rocks.

In 1884, her hull strained and worn almost paper-thin, she was laid up on a sandbar where her crumbling bones remained for years as a sad reminder to passersby of one of the greatest days in B.C. marine and railway history.

The spirit of S.S. Skuzzy, long remembered as the “White-water Boat,” lived on, however, Onderdonk having installed her steam plant in the 140-foot Skuzzy II. For 13 years the second steamer of this famous name plied the Thompson River until she, too, was retired. Remarkably, her ancient machinery again went to work, this time in the steamer Lytton on the Upper Colombia River.

The spirit of the Skuzzy was just another achievement of the amazing Andrew Onderdonk in his construction of the infamous Port Moody-Kamloops line. No less an accomplishment had been his having built 16 tunnels. Finishing on schedule, he contracted for the extension to Eagle Pass and completed this section on Sept. 30, 1885.

A week later, he paid off his men. As 1200 Chinese labourers quietly marked the historic occasion by setting up camp in the woods, 1,000 white construction workers embarked on a monumental drunk at Yale. After taking possession of the town, several “lunatics,” according to one newspaper, even “attempted to force their way into private homes".

An odd note on which to conclude this remarkable story of human ingenuity and endeavour.

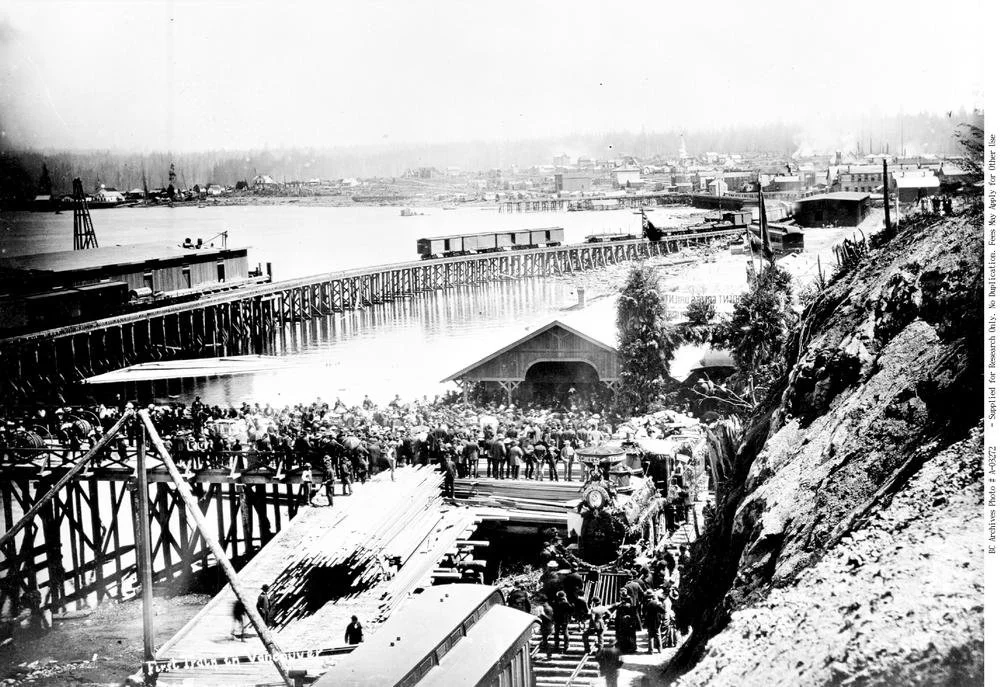

The arrival of the first transcontinental train at Port Moody. --BC Archives

* * * * *

In the summer of 1978, a 34-foot aluminum boat powered by a 475 horsepower V-7 engine coupled with a 12-inch jet, rather than a propeller, braved Hell’s Gate Canyon. Designed and operated by Prince George residents Howard Whitt and Gary Reinelt, the mis-numbered Skuzzy II (it should have been Skuzzy III) was forced to turn back before the incredible onslaught.

“It was like hitting a solid brick wall,” Witt said.

Twice, Skuzzy II had grappled with the overpowering current. At one point the daring duo were within 10 feet of victory before being forced to turn back. At last report, Witt and Reinelt were again preparing to brave Hell's Gate when the water level fell in autumn.

* * * * *

Engineer Onderdonk went on to other accomplishments in South America, the U.S. and Eastern Canada. Some historians have considered his building of the first subway tunnel under New York's East River to be his greatest achievement.

But others recall that long-ago day when little Skuzzy dared the swirling rapids of Hell’s Gate Canyon. This, they maintain, was Andrew Onderdonk’s finest hour.

* * * * *

Which brings us to the matter of how he treated his Chinese employees. For my tentative answer, please see today’s Editorially Speaking.

These Chinese workers are digging a canal but it’s likely a scene that prevailed during Onderdonk’s railway building through the Fraser Canyon. —BC Archives