Second Narrows’ ‘Bridge of Sighs’

We’ve just passed the 66th anniversary of that tragic day in June 1958 when two spans of Vancouver’s new Second Narrows Bridge, then under construction, collapsed.

Two weeks ago, the Langley Advance marked that momentous event with an interview with Lou Lessard. Now 91, the former ironworker is the last survivor of that horrendous event of June 7, 1958.

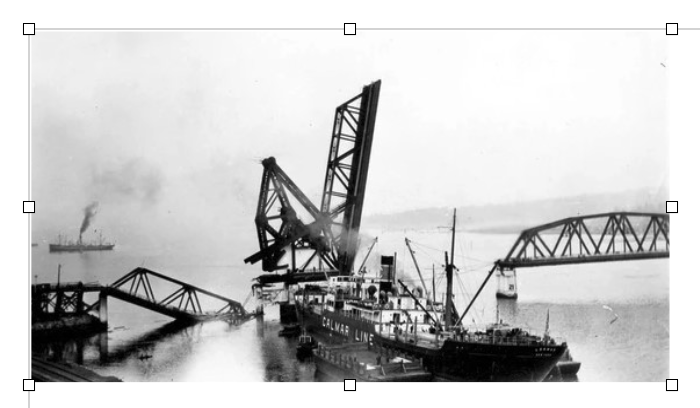

This scene is so calm and peaceful it’s hard to believe that, just days before, 19 men died in a thunder of crashing steel. —Vancouver City Archives

What few realize is that the first Second Narrows crossing, which opened in 1925, had soon became known as the ‘Bridge of Sighs’ because it seemed to be jinxed. Hardly had the paint dried than it was struck no fewer than four times by tugs and log booms. That was before it even entered service in November 1925.

For the next five years, as an American shipping magazine sarcastically noted, the bridge was “constantly involved in accidents and lawsuits”.

* * * * *

A second Burrard Inlet crossing (the first being the Lions Gate Bridge) had been a gleam in the eyes of city fathers and the business community as far back as the turn of the last century. But it was 1907 before an aspiring railway, the Vancouver, Westminster & Yukon, announced an interest in spanning the Second Narrows.

This never-been-heard-of since railway was the brain child of lumber baron John Hendry who’d conspired with the American-owned Great Northern Railway which had hopes of breaking the CPR’s virtual monopoly of the Lower Mainland. Presciently, as events turned out, a Province editorial dismissed the proposed bridge as a threat to marine traffic that would “dam” the eastern reaches of Burrard Inlet beyond Hastings Townsite.

Contrarily, the competing World noted in a front-page story that the proposed bridge would be 50 feet high with a centre swing-span, sufficient to allow large vessels to pass through. An accompanying artist’s conception showed a nine-pier bridge 1560 feet (475 metres) long that would, in the words of the World, be “one of the most magnificent bridges in the whole west”.

Initially, the city and adjacent municipalities showed interest. But the proposal’s greatest shortcomings, in the words of John Mackie in a 2028 retrospective, This Week in History: 1907, were that the bridge was intended solely for railway traffic and the VW&Y wanted full proprietorship. So the bridge never left the drawing board.

Three years later, the municipalities came up with their own scheme for a crossing but before any funding agreement could be made, the First World War took precedence over all. Not until 1923 did the neighbouring fiefdoms agree to jointly construct what would become known as the first Second Narrows Bridge. It finally opened to vehicular and pedestrian traffic on Nov. 7, 1925.

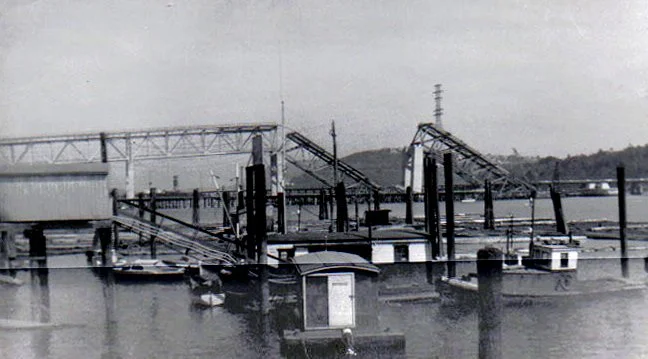

Two views of the original,gangling toll bridge. —Vancouver City Archives

Its proud owners’ fondest hopes seemed justified when, to again quote John Mackie, the new bascule bridge with a pivoting section that was raised and lowered with weights to allow for marine traffic, “was an instant hit”. A continuous stream of automobile and foot traffic—16,000 cars and 35,000 people—crossed over in the first three days. This, despite the fact it was a toll bridge that charged 15 cents for cars and a nickel for each passenger and pedestrian. (Its rail deck wouldn’t enter service until the following year.)

The Vancouver Evening Sun welcomed its opening with an almost lyrical full-page story and photo, headlined, A NEW LINK TO PROSPERITY.

“Just as the military highways that Rome extended across Europe made possible the prosperous and wealthy Roman Empire, so does the bridge now thrown across the Second Narrows help to make possible the prosperous and wealthy civic empire of Greater Vancouver...

“The new bridge brings North Vancouver into the metropolis. It opens up to Vancouver, the wealth, health and happiness that lie on the North Shore. The new bridge is a Roman Road, an achievement that will link up two communities for mutual welfare, mutual success and mutual prosperity.

“It is the beginning of a greater life for Greater Vancouver.”

But the honeymoon didn’t last last long, thanks in part to the strong tidal currents of the Second Narrows that bedevilled navigators. In the first years of the bridge’s career, 16 major accidents caused damage and resulted in claims amounting to approximately $1.5 million—including the cost of replacing 300 feet of the span that took three years to replace.

Accidents involving ships entering and leaving the upper end of Vancouver Harbour occurred, in fact, with such regularity that it became known as the ‘Bridge of Sighs’.

The first mishap, involving the American freighter Eurana, took place Mar. 10, 1927 when the ship suffered a repair bill of $30,000 after grazing the bridge. The same day, the tug Shamrock incurred damage to the tune of $10,000 under similar circumstances. On April 24, 1928, a British merchantman, the Norwich City, struck. The repair bill: $50,000.

The heavily damaged British freighter Norwich City, April 1928. —Vancouver City Archives

Precisely a year later, the American freighter Losmar crashed into the span resulting in a damage claim of $100,000. By far the most expensive incident of this unhappy period involved the Pacific Gatherer, the log carrier having become wedged under the bridge at a cost to underwriters of a quarter of a million dollars.

The venerable steam tug Lorne struggles to free the Pacific Gatherer, an old sailing ship which had been converted to a barge, from the heavily damaged bridge, shown below. —Vancouver City Archives

This was the incident that toppled the bridge, only three years old, into the Narrows. Wedged tight, the barge rose with the tide and lifted the span from its bearings and supports.

Once again, the engineers went to work and, in 1934, a second Second Narrows Bridge was opened to traffic. Fortunately, due to a drastic change in design, the second bridge behaved itself—almost—the accident rate declining sharply with the new span’s greater clearance for shipping. When problems did arise, the damage was notably less—in 10s of 1000s of dollars, rather than 100s of 1000s.

One of the worst mishaps of the post-war years was that of the Norwegian freighter Bonanza which was swept broadside into the bridge by a flood tide. Only quick action on the part of the bridge operator prevented greater destruction. Upon seeing that collision was inevitable, he’d raised the centre span. As it was, the Bonanza lodged tight.

Ten tugs and cutting torches were needed to free her from the bridge’s steel talons. The bridge paid dearly also, having to be closed again for repairs.

(To give an idea of the busy marine traffic through the Second Narrows, in 1952, 28,000 vessels passed under the bridge which had to be raised 5000 times.)

Yet, when the bridge’s own turn came at last in the summer of 1970, many Vancouver motorists mourned the passing of an old—if cantankerous—friend. Early on a July morning, salvage crews torched away the bridge’s 800-foot centre span and lowered it onto a barge for the final tow to a Tacoma scrap yard.

As Vancouver Sun marine reporter Charles DeFieux observed, perhaps tongue in cheek, “The structure could wind up as plates for a ship.”

Bought by the CNR for a dollar in 1964, the 45-year-old bridge was closed when the railway constructed a new span alongside.

In its final years the ‘Bridge of Sighs’ had become known as the ‘Golden Goose,’ having reaped large dividends in the way of tolls for its shareholders, the municipalities of Vancouver, West Vancouver and North Vancouver City and district.

This was only fair, actually, as the Pacific Gatherer disaster of 1930 had bankrupted the North Shore communities!

“It was quite a bridge in its day,” said one longtime resident while watching the demolition in 1970. "Yes, sir, quite a bridge."

Throughout the bridge’s colourful history, there were those who considered its frequently unbecoming conduct the work of evil spirits—those of ancient warriors who’d been dispossessed in 1923 when the tiny Island which once squatted beneath the span was removed. Tribal legends had long maintained that Hwa-Hwoi-Hwoi was sacred ground.

Today, 130-odd thousand vehicles daily cross the present Second Narrows Bridge that today links Vancouver with the North Shore. Few of them probably spare a thought to the disaster that stunned the province almost 70 years ago.

Work on the new bridge, costing $15 million and two miles long, progressed steadily for more than two years although four workers had already died in mishaps. By June 17, 1958, the enormous steel dinosaur straddling tall concrete pilings was visibly taking shape.

Under construction prior to the collapse. —Edward F. Irvine photo, Wikipedia

That afternoon, scores of construction workers clambered over the bridge, their regulation life jackets bright checks of yellow against a backdrop of gaunt ribs of rust-coloured primer paint.

When disaster struck, it came swiftly—15 seconds of thunder and waves precipitated when a crane “stretched from the north side of the new bridge to join the two chords of the unfinished arch [and] several spans collapsed”.

Patrol boat operator Ken Johnstone was looking forward to calling it a day. It was 3:30 in the afternoon. Another hour of manoeuvring his little outboard beneath the bridge and he could go home. For a month, he’d made his monotonous rounds, ready to rescue any worker who should fall into the Narrows’ sweeping current. June 17th was simply another routine day—until 3:40.

Then, just as Johnstone was “positioning the boat beneath the second from last constructed span, I heard a noise that sounded like thunder. I immediately looked at the unsupported end of the bridge. I was 80 yards from it—and saw it plunge into the water. Immediately, it seemed, the second span, between two casements, was pulled forward into the water. The whole collapse seemed to take only a few seconds."

A few seconds in which 1000s of tons of folding steel and dozens of men were dumped into the Narrows.

How could anyone have survived this jumble of crushed steel girders and frames? —Vancouver Sun

Starting his tiny runabout, Johnstone waited for the ensuing tidal wave to subside for him to advance. “Twenty yards away, a man was swimming...and trying to remove his life jacket which hindered his swimming. I got him in the boat and took him to shore. Then the engine gave out and I had to row." Engine or no, Johnstone returned again and again to the still groaning wreckage, feverishly searching for the men who’d plunged with it.

For one man who’d been trapped in a jungle of crumbled steel, Johnstone quickly ferryied a rescuer with a cutting torch; on another mission, he recovered only a helmet from beneath the debris.

Painter Anthony Romaniuk was scraping rust from girders, 100 feet above the inlet, when the tragedy occurred.

Seconds later, he was underwater, strapped to a girder by his safety belt. "I thought I was drowning, I kept telling myself not to panic... I knew I had to get the belt off as fast as I could and I just forced myself out of it." Somehow, he reached the surface.

Side view of the collapsed bridge. —Vancouver City Archives

Twenty-four-year-old Don Gardiner was at the very top of the outermost span when it fell. “It was horrible,” he recounting. “Everything happened in a split second. The steel seemed to drop about five feet, then dropped a little bit again, and then fell into the water."

Bill Hallman was driving across the old Second Narrows bridge, about 200 yards to the east, when “the air was filled with shouts and cries. At first it looked as if our bridge was falling... 50 men must have gone down with the bridge. They didn't have a chance. It all happened in a moment. When they hit the water I could see some grasp for pieces of driftwood.

“It appeared about half of the men were trapped underwater by the bridge sections. Others were swept away by the current."

The end section went first, continued the horrified motorist, “and the one to the north a moment later—they just nosedived down. There were two tugs and a small boat nearby. We yelled to them and directed them to the survivors.”

“Boom, boom, and then I was in the water," recalled ironworker Gary Poirier. The 19-year-old was on the outermost span but escaped with only a leg injury. He said he “fell about 100 feet and went under about 15 feet. When I came to the surface, I found my life jacket had been torn but I managed to hold onto it and to a piece of floating timber until I floated to the old bridge.” There, he was hauled aboard a boat.

Even luckier was Sam Ruegg who’d been standing on a pillar when the crash came, the tumbling girders missing him by inches. At the first scream of tortured metal he’d thrown himself to the concrete. He later told the investigating Royal Commission that he’d “had a premonition all that day [that the bridge would collapse]. I picked the safest spot on the bridge to go if something happened."

Death or rescue came swiftly for most of the 79 men who plunged with the wreckage. It’s thought that some drowned after they were pulled down by the weight of their heavy tool belts.

However, for 30-year-old ironworker John Olynyk, the disaster had seemed an eternity. He and another worker were on the half-constructed fifth span. They’d just changed places when the bridge crumbled, plunging both into the water. His partner was killed instantly, Olynyk trapped underwater.

Frantically, he struggled in the surging blackness, fingers clawing for a hold, until he was able to poke his head through a diagonal. "While I was waiting, I could feel the water rising fast. The water was around my shoulders when the cutting torch came. I was afraid I would drown—it was a living hell."

Eventually freed, the 200-pounder was treated for abrasions and sent home.

Another young workman's ordeal proved to be agonizingly long after he came to rest in the mangled steal a few feet above the water. Not until he looked down did he realize that a leg had been severed above the knee. Incredibly, he removed his belt and strapped it about the thigh as a tourniquet—then smoked a cigarette until rescuers freed him.

And so it went as pleasure and harbour craft of every description raced to the scene to recover smashed men from the debris. As the hours passed, the number of rescue vessels rose to 64 as police and construction officials laboured on the list of those working on the span when it fell. Skin-divers, their rubber suits almost melting them in record 81° F heat, plunged again and again into the hazardous eight-mile-an-hour current.

Finally it was ended.

A week later, all bodies (which had overflowed both the hospital and city morgues) had been recovered but three, believed to be trapped in the spaghetti of broken girders. Then, on June 27th, 10 days after the crash, the haunted bridge claimed yet another victim, this time one of the many skin-divers still hunting for the missing bodies.

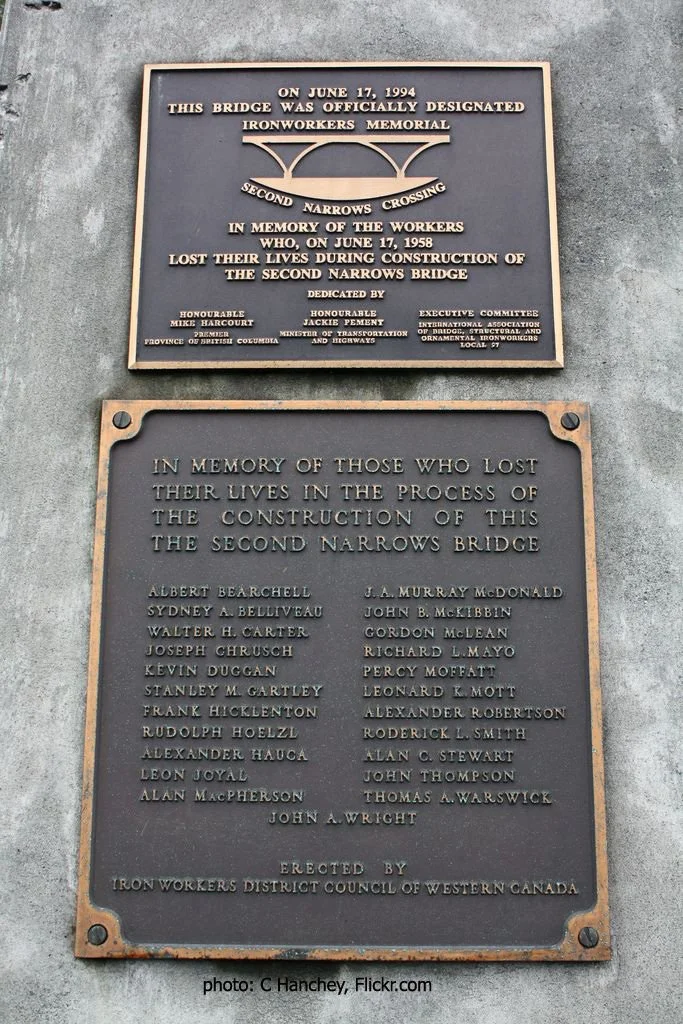

On August 25, 1960, a crowd of more than 1000 stood silently in a drizzling rain as Mrs. John A. Wright, whose husband died in the collapse, unveiled the plaque listing the 23 men killed in the bridge’s construction.

When Survivor William Wright cut the Blue Ribbon, the Second Narrows Bridge, second largest cantilever span in Canada, was officially opened.

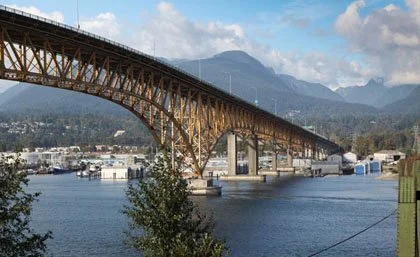

The Second Narrows Bridge as it is today. —The Canadian Encyclopedia

It was renamed the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing in 1994.

Another poignant tribute to this historic tragedy is the iron ring worn by all Canadian engineers. According to legend but, alas, not so, the rings are supposed to be cast from iron from the fallen bridge. The ring symbolizes the responsibility engineers have, that they “should build safely, not for monetary gain but for the science and art of their craft”.

* * * * *

A Royal Commission established to determine the cause of the crash concluded that “a temporary bent, designed by an inexperienced engineer and inadequately checked by a senior engineer failed...[and led] to the collapse of two spans... Flawed material and procedures, and inappropriate safety standards that resulted in failure” also contributed to the bridge’s collapse.

* * * * *

This plaque lists the names of the Bridge’s 23 victims.—BC Labour Heritage Centre

Twenty years later, ironworker Bill Stroud told Vancouver Province reporter Dennis Bell of his narrow escape from death. Incredibly, he remembered it with wry humour, telling how he’d been dropped 100 feet into the water, injuring his back and having to wait almost two and a-half hours for rescue.

Come next payday, the Dominion Bridge Co. docked him half an hour’s pay for leaving the job early!

For the 60th anniversary the CBC interviewed Gary Poirier whose close call is previously described. Moments before the disaster, while 100 feet above the water without safety belts, he and a supervisor were inspecting bolts on a steel beam when he felt the bridge lurch.

“That’s when all hell broke loose,” he said. “I wasn’t hurt that bad” and, taken to hospital, his first concern was to inform his mother that he’d survived. Upon recovery he returned to work on the bridge, helping to dismantle the wreckage. “The work had to go on and I had to continue to make a living...”

In June 2018, he said with visible emotion, “It’s never going to go away. It’s a memory I can’t forget.”

More recently, 91-year-old Lou Lessard, the last of the surviving ironworkers, attended the 66th commemoration of the disaster. It was an ordinary day on the job, and hot, he recalled. A foreman, he’d ordered his 10-man team to unload 55 tons of steel from a rail car to the bridge deck, a gruelling job that, once begun, had to be finished.

The bridge collapsed when he was 150 feet above the Narrows and he later figured that he plunged a further 35 feet after hitting the water with such force that it tore his life jacket from him. But: “I was lucky. I was at the edge of the bridge, I fell free from the wreckage. Otherwise, I would have been dead, too.”

Upon resurfacing he heard screaming and crying and saw bodies floating around him.

Thinking of his young child at home, and with one arm useless, he squeezed some broken planking under each armpit to serve as floats until he was picked up by a small boat. At first, doctors thought they’d have to amputate his leg but were able to save it. He spent four months in hospital before returning to work on crutches.

Lessard, who’d continued for another 40 years as an ironworker, attended every Second Narrows Bridge memorial service since: “We promised those guys that we were never going to forget about them... That is important to me. We made a promise.”

* * * * *

In 1962, American country singer Jimmy Dean paid tribute to the lost workers in his ballad, Steel Men. Ten years later, Canadian folk singer Stompin’ Tom Connors also memorialized the tragedy with his The Bridge Came Tumbling Down. Poet Gary Geddes entitled his tribute, Falsework, a reference to the temporary supports that failed so disastrously.

* * * * *

Today’s Second Narrows crossing is a steel truss cantilever bridge designed by Swan Wooster Engineering Co. Ltd. Construction began in November 1957, and the bridge was officially opened on August 25, 1960. It cost approximately $15 million to build.

The bridge is 1292 metres (4239 feet) long with a centre span of 335 metres (1099 feet). It is part of the Trans-Canada Highway (Highway 1).

* * * * *