Editorially speaking…

There just ain’t nothing sacred any more...

It’s looking more likely that a Vancouver mining company will get the go-ahead to “process the large quantities of waste rock on land owned by Mosaic on Mount Sicker...” reads the lead of a front-page story in this week’s Cowichan Valley Citizen.

The waste rock referred is that of the ore dumps and tailings piles of the historic Lenora and Tyee mines on Mount Sicker.

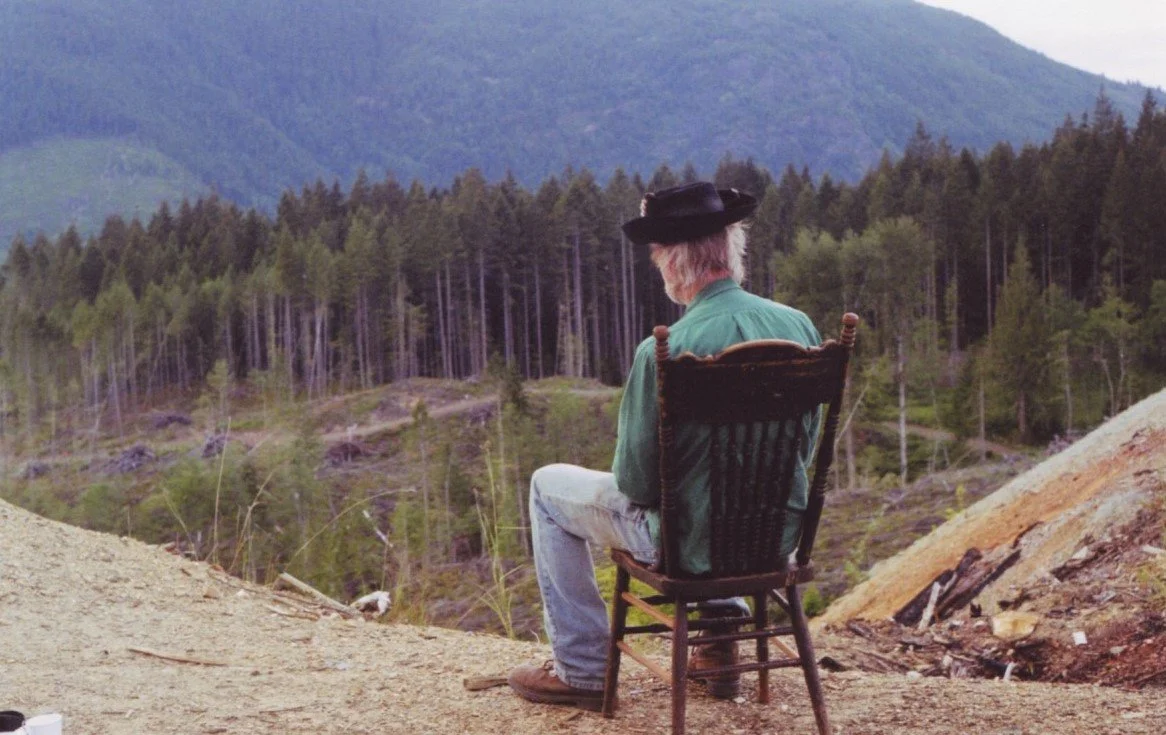

I’m sitting atop the Tyee Mine ore and tailings pile, looking towards Copper Canyon and Mount Brenton. The chair, courtesy of the late George Compton, is from the dining room of the Mount Sicker Hotel in Lenora town site, which was on the slight rise that shows just above my left knee. If plans to re-process these mineralized gravels and rocks go through, this view will no longer exist.

—Author’s Collection

I can live with their processing the waste from the Lenora Mine, which is mostly in the form of gravel dating back to the Second World War when this turn-of-the-last century copper mine had a second lease on life. The company is seeking precious metals that weren’t recovered by earlier processing and smelting methods: gold, silver, copper, lead and zinc.

These gravels will be hauled away for processing elsewhere, leaving, the company promises, a “pristine” remediated landscape when they’re done. So far so good; it’s just a gravel pit today, with little other than scrub growth in the way of vegetation.

But Tyee Hill, as I call the Tyee Mine ore pile, is another kettle of fish. This is not just a gravel pile, but a 50-foot-high, man-made hill containing real chunks of chalcopyrite and rocks. So, big deal, you say?

Every one of those rocks was brought to the surface by miners who had to drill, blast and haul them to the surface by hoist, the Tyee Mine descending 900 feet down. Upon being hauled up in a barrel by its man-powered windlass for hand-sorting, the visibly mineralized ore was sent off to the Ladysmith smelter via the company’s tramway. Crude, but effective—both mines were, if only briefly, fabulously rich.

Jennifer Goodbran poses midway between the Lenora and Tyee mines, looking up at the Tyee ore dump. Because the camera shortens the depth-of-field, the pile looks much smaller than it really is. Soon, if all goes according to plan, ‘Tyee Hill’ will be hauled away for its remaining precious minerals. —Author’s Collection

The vertical shaft, originally fenced off then filled in by the government in the 1980s or so, was situated in the very centre of the tailings pile. Its down this chute, in August 1901, that foreman Charlie Melrose fell to his death, breaking almost every bone in his body—without receiving so much as a mark on his face.

The irony is that, today, the top of the Tyee ore/tailings pile, which offers a panoramic view of the Lenora town site below, and Copper Canyon and Mount Brenton farther to the west, has served for years as a place to party. Many a beer can have we salvaged during our visits.

Not to mention some great artifacts, including the copper nameplate from an ore car, which always makes me think of a policeman’s badge when I look at it. I mean, it’s thick, heavily and nicely cast—a treasure among my museum of mining artifacts. This one and others from the Mount Sicker Copper boom are destined for the Cowichan Valley Museum in due course.

But back to reclaiming these ore piles, which will be the third time over 120 years that the Lenora and Tyee properties have been milked for their mostly copper treasures. It’s interesting that Sasquatch Resources has determined that there’s still enough un-recovered value to justify their efforts and expense.

North Cowichan Council sees it as a win-win: an environmental clean-up and a boost to the local economy. I’ll mourn the removal of ‘Tyee Hill’ as one more historical icon sacrificed to ‘progress’. I guess I’ll have to settle for having my memories and my photos.

I’m sure glad now that I wrote my 2007 opus, Riches to Ruin: The Boom to Bust Saga of Vancouver Island’s Greatest Copper Mine. Short of someone recycling the book for its paper, it, with its fabulous story of Mount Sicker, will carry on.

* * * * *

Okay, so I slept through Labour Day. By not acknowledging this historic holiday in last week’s Chronicles, I mean. But I’m sure to write again about our B.C. labour history in the lean and mean years of the Great Depression and of the Great Strike in the Vancouver Island coal mines, 1912-14.

Labour stories do pop up often in my online research, including this recent nugget from the BC Labour Heritage Centre (labourheritagecentre.ca) about the first longshoremen in Burrard Inlet. I’m sure that readers will be as surprised as I was that these workers were members of the Squamish Nation who, in the 1860s, provided most of the stevedores for loading and unloading ships.

Hence, in 1906, Local 526 of the International Workers of the World was formed and fondly identified as “the bows and arrows,” although its membership included other nationalities and ethnic groups.

* * * * *

The bitter and the sweet.

Over the holiday weekend, the BC Forest Discovery Centre celebrated the return to service of the Hillcrest No. 1 Shay locomotive after a total rebuild. This is wonderful news but the renowned No. 1077 locomotive at Fort Steele spent the summer in mothballs, having been laid up, with its able and eager volunteers, by the society that operates the popular historic site.

Like the No. 1, the No. 1077, which has starred in movies, just turned a century old and is one of the few steam locomotives still operational in western Canada.

Which reminds me to look into what’s happening at the Yale Museum which also has been gobsmacked by a change of direction from the province.

But not this week.

* * * * *