Victoria’s Odd Couple

Although totally unlike the characters in the 1970s TV sitcom, William and Amelia Copperman must be regarded as Victoria’s very own Odd Couple. Their strange and stormy marital partnership amused, amazed and outraged fellow citizens for 15 incredible years.

They’re yet another reminder that they just don’t make real characters like they used to!

* * * * *

Victoria was still a Hudson’s Bay Co. outpost when the Coppermans first set up shop on Store Street. From this humble beginning, they began to prosper, but life was anything but quiet. —Author’s Collection

Little is known of their background before they arrived in Victoria in 1858 and occupied a small shanty on Store Street which doubled as living quarters and trading post. Business prospered from the beginning but the Coppermans’ commercial prowess paled alongside their talent for getting into trouble.

The first recorded court case lists William Copperman as plaintiff. Subsequent appearances before the bench often saw the fiery husband and wife, together and individually, in the dock as defendants.

Whatever, William's initial experience with the law saw him charging an Indigenous man with stealing, of all things, his dog. Convicted, the hapless man was sentenced to “vegetate” in the chain gang for 10 days.

It was then Amelia's turn to play the role of injured innocence by charging a business neighbour, Carlo Bossi of Johnson Street with having assaulted her—by throwing a basin of dirty water in her face. This unpleasant affair began with a Native woman pocketing several handkerchiefs from the Coppermans’ stock then retreating to Bossi's store. Hot upon her heels went Mrs. Copperman.

She proceeded to search all Native women present—but no came up with no handkerchiefs.

Pioneer Victoria merchant Carlo Bossi as he appears on his headstone. The Bossi monument is one of the most expensive and elaborate in Ross Bay Cemetery. —Courtesy Old Cemeteries Society

Indignant at her invasion of his premises, Bossi remonstrated. Mrs Copperman replied somewhat sharply and....the argument ended with the pan of airborne dirty water. To Amelia’s dismay, the magistrate was less than sympathetic, regarding the affair as “one of those quarrels that will occasionally arise between neighbours”. He fined Bossi one pound.

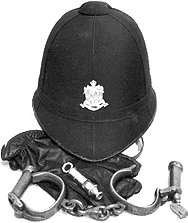

Four months later, it was William's turn to bask in the spotlight although in decidedly different circumstances, a fight at Johnson Street that resulted in charges of creating a disturbance and resisting arrest for the two combatants. They were duly fined 50 Shillings each, but William was billed five pounds for having obstructed justice by laying his hand upon a constable's arm and complaining, "It's a damn shame to arrest that man.”

Despite an eloquent appeal by defence council, Copperman was forced to cough up the fine and listen to a stern lecture on the follies of obstructing a policeman acting in the line of duty.

When next William faced the magistrate it was to answer a charge of having received stolen goods. This almost comical charge was laid by a young labourer named Peter Jones. Placed on the stand, Peter identified the “pags” by the stitching, a hole, and the fact they contained traces of sawdust. Under questioning by defence counsel Ring, the plaintiff explained how he’d missed his sacks, saw them among Copperman's effects, then called a policeman.

Asked how he could be so positive as to the sacks’ identity, Peter heatedly replied, “Let me talk some myself, Sare; you want to talk all the time. I pegs your pardon, but I want to dell how it happened.

“Mr. Copperman, he lent me pags two or three times and I always took them dem back; yesterday I missed my five pags and I went to every house in Victoria to look for them dem. Den I goes to Copperman's house and looks apout and I see te five pags, and I say, ‘Copperman, you got my sacks, what you say, eh?’”

William ordered Peter out of his store and pushed him, which is when Peter called for reinforcements in blue. Peter further identified a sack by a “fringe about te top”—his favourite bag. Holding it affectionately, he mused aloud, “yes, my leetle fringe pag,” to spectators’ delight.

In rebuttal, Mr. Ring called four character witnesses who glowingly testified to Copperman's estimable qualities, each asserting that the gunny sacks could in no way be distinguished from 100s of others. Copperman ended the case for the defence by admitting that the bags could conceivably belong to Peter, quote if so, they’d been left with him in return for others Peter had borrowed.

The magistrate acquitted him on grounds of insufficient evidence although he was sure that the bags probably were Peter’s. When the court was cleared, Peter hurried away with his beloved “leetle French pag,” tears of joy streaking his brown cheeks.

The Bastion Square Police Barracks, centre, witnessed human drama of all kinds, including William and Amelia’s jousts with the law. —BC Archives

Hapless William had no sooner disposed of this threat to his liberty and good character than he again found himself in the dock, this time accused of assaulting a clerk of solicitor Dennes.

The clerk had inadvertently left one of his employer’s business letters at the Copperman store. Naturally, William had to read it to determine its ownership. When the clerk anxiously returned to reclaim possession, he found himself facing Copperman’s wrath. Incensed by the missive’s contents, William cursed him loudly and struck the frightened clerk on the chest, at the same time “expressing a wish to serve Mr. Dennes in a like manner if he could lay hands on him”.

Regrettably, Mr. Dennes chose to meet him in the arena of justice rather than on the field of honour; the verdict 50 shillings.

Precisely a week later, busy Mr. Copperman was answering an accusation of theft. But this time, the case didn't reach court. Upon returning from Nanaimo, Bill learned that a miner who’d left furniture in his safekeeping had charged him with stealing it.

Raged Copperman in a newspaper advertisement, “I heard nothing... about it until I came back from Nanaimo this evening, when I learned that the officers had been [to his store] with a search warrant, and had taken everything away. They also searched my private house—what business had they there? And what business had Sgt. Blake to enter my private house in my absence, and threaten to take my wife up?

“And now I beg of Judge Pemberton that he shall insist that the man who made the complaint against me of ‘felony,’ shall make good his charge, or suffer punishment.”

As nothing more is recorded of the case we must give William the benefit of the doubt and consider his honour unstained.

When next he astounded Victorians, it was from his ‘deathbed,’ the result of an altercation with a man who was visiting friends in a cottage at the rear of the store. When the man and his lady friend became drunk and noisy, the ever irritable William ordered them off the property and shoved the man.

The latter replied with a blow of his fist, at which the storekeeper grabbed a stick and beat him about the head “until the blood flowed," then returned to his store. Just as he was closing the door, a jagged stone caught him on the forehead and knocked him to the floor, unconscious. While being kicked again and again in the groin, Copperman regained consciousness, grabbed a hatchet and brought it down with all his might upon his assailant’s temple.

This ended the bloody battle and both gladiators sank, senseless, to the floor.

For days, Copperman lingered in critical condition. Upon recuperating sufficiently to appear in court, it was to again have the magistrate disagree with his version of events. Both parties were judged to be equally responsible. For inflicting the more serious wound, William’s attacker was fined five pounds; for failing to have him ejected by a policeman, the latter was nicked one pound.

Then it was Amelia's turn to appear in court, she having charged Fabian Mitchell with assault. Magistrate Pemberton, as usual with the Coppermans, thought otherwise, found only that Mitchell had “acted in an unmanly way,” and bound him over in the sum of 10 pounds to keep the peace, or 14 days.

William played defendant for the last time when he was charged with receiving stolen goods from the wrecked vessel Nanette. He was remanded for trial and released on $4,000 (then an astronomical sum). Interestingly, testimony during the preliminary hearing had concerned a mysterious payment of $5,000 by Copperman to Mrs. C., which, it was revealed, had been the couple’s settlement, William having divorced Amelia according to Hebrew law because they remained childless after 11 years’ wedlock.

This is our last reference to Mr. Copperman, final disposition of the stolen property charge not being recorded. He soon sailed for Germany and remarried.

Poor Amelia didn’t fare well at all, becoming more adept than ever at courting disaster—even when it wasn’t of her own making. One winter night in 1864, having heard of the treasure she supposedly kept beneath her bed, two thugs burst through the outer door to her living quarters. They’d forced their way into the frightened woman's boudoir when watchman Thomas Barrett reached the scene.

Reported the Colonist: “The Ruffians sprang upon and beat him on the head with their pistols. The sound of the affray was heard by policeman Curry, a fine young Irishman of 22 years. As he entered the premises the robbers rushed past him, and the watchmen, his eyes blinded with the blood that flowed from 20 wounds on his head, fired his revolver after them and shot poor Curry through the heart.

“Mrs. Copperman saved her treasure, and Curry lost his life."

(Constable John Curry was Victoria’s second police officer killed in the line of duty. —Ed.)

The Victoria Police Department’s website, www.vicpd.ca, describes Constable Curry’s death in the line of duty in greater detail. —Victoria Police Department

A year after, Amelia suffered yet another appearance in court when the neighbouring Dobrin children broke one of her windows while playing. Waving a large stick, she charged in pursuit and Mrs. Dobrin, rushing to her children's defence, used the came on her!

The court ordered the harassed storekeeper to post bonds to the tune of $200. This is the equivalent of $5100 today, suggesting that the court was losing patience with Amelia.

As the records show, magistrates invariably sided with the opposing team, be they plaintiff for defendant. When Amelia accused an employee of stealing a pair of cheap trousers, another trader confirmed the man's testimony of having received the pants in lieu of back wages. Magistrate Pemberton issued a caustic warning for her to “employ more trustworthy servants".

Then she charged a man named Jacob with calling her names and pulling her nose. Quite in self-defence, of course, she threw a cup of water in his face, at which Jacob knocked her down and kicked her in the breast. Witnesses agreed that Mrs. Copperman provoked the fight but, as she’d been seriously injured, Pemberton fined Jacob $20. For throwing a cup of water, he fined Amelia $10!

A Colonist reporter sadly commented, "Mrs. Copperman ought to have a husband or guardian to look after her affairs, as she is utterly incapable of doing so herself."

Her disasters continued without break. In court over the possession of a $50 watch, for which she’d accepted an advance of $10 then denied ever having seen the timepiece, she not only lost the case but was warned by the judge that she’d be charged with perjury. She seems to have escaped the latter threat.

As the years passed with Amelia growing older and more irascible, Victorians took to calling her "Mother” Copperman; if not with affection, possibly out of tolerance.

Charged with forging her landlady's rent receipts, despite the fact that it was common knowledge she’d made a fortune over the years, Amelia fled to the ‘other side’ (Washington Territory). Laughed one newspaper, "She has proven herself as great an adept at forging that she ought to go into the blacksmith business”!

Three weeks later, she returned to face the music, perhaps heartened by rumours circulating Victoria to the effect she’d been “shanghaid”. She needn’t have fled as it turned out, Chief Justice Begbie and Justice Crease finding her innocent of all charges.

Even a record as amazing as ‘Mother’ Amelia Copperman’s must end. In 1874, upon convicting her of selling ‘tangleleg’ whisky to Natives, Magistrate Elliott fined her $100. Two years later, Amelia was taken ill while attending a wedding at Sitka, Alaska. She retired to the porch, lapsed into unconsciousness and never recovered.

One of Victoria's more infamous yet, in some ways, sympathetic characters was history.

Somewhat to my surprise, I found an entire chapter dedicated to Amelia Copperman in City In Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past by May Q. Wong, Touchwood publishers, 2018. The author views Amelia much more sympathetically than have other historians, myself included, because of her likely background previous to Victoria when she’d experienced the anti-Jewish pogroms of Europe, then her isolation in outpost Victoria as a single woman after William divorced her.