Frank Swannell

Iconic explorers and the builders of the Canadian Pacific Railway aside, not many Canadian land surveyors have achieved national stature.

In his day, Victoria-based Frank Swannell (1880-1969) was the exception, nationally recognized for his incredible feats with both a transit level and a camera. Over 40 years, on foot, on horseback and by canoe, he probably covered more British Columbia terrain than any other man before or since.

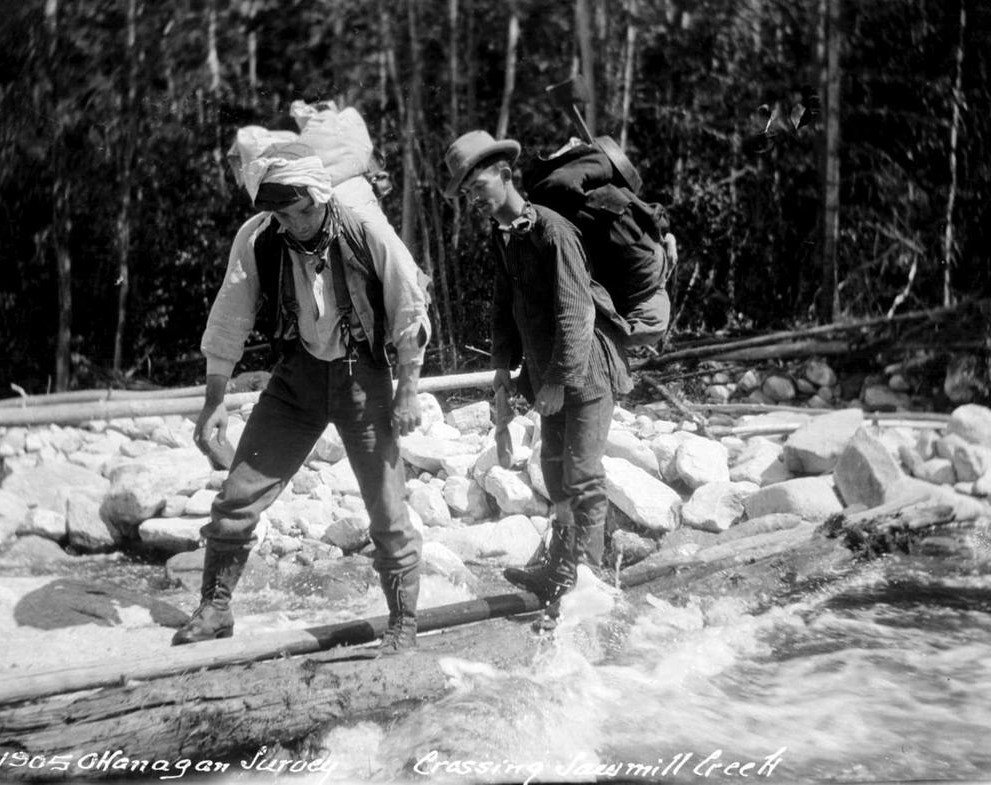

What now can be done by aircraft in hours he, and those who worked with him, had to do it all the hard way, by battling mountains and streams, weather, mosquitoes and black flies, and every manner of physical hardship as a daily fact of life; the cost of doing business, so to speak.

But Swannell’s legacy is greater than his hard-won surveys—he added to his daily struggles in the wilds by lugging along a camera. The result is a priceless legacy now in possession of the BC Archives—5000 quality photographs, many of which are now available online and, in recent years, in a coffee table book, Surveying Northern British Columbia: A Photojournal of Frank Swannell, by Jay Sherwood.

These black and white images not only capture the day-to-day life of a survey party at work (and sometimes at play) but record landscapes as they were and, in many cases, are no longer.

* * * * *

When you think about it, it’s a minor tragedy that few land surveyors of any nationality have achieved public recognition when we consider all that they willingly endured on a daily basis. Theirs was no job for the weak. Forgoing the routine of 9-5, they endured the 24/7 physical discomforts and other hardships as they went about their work almost year-round and in all weather conditions.

With their transit levels and the other requisite tools of their trade—muscle, rifle, axe, fishing rod and camping gear—they not only surveyed the land, but recorded the topography and took note of soil conditions for government study. All this required a sense of drive and determination that few of us, today, choose to apply to our own vocations.

Frank Cyril Swannell took this sense of dedication to its highest level, the twice-wounded war veteran seeing firsthand as much of the province as any other living man during his four-decade-long career.

Please note: Today’s Chronicle isn’t meant to be even an attempt at an in-depth profile of Frank Swannell, but a thumbnail introduction to this remarkable man and a preview—the tip of the iceberg—of his photo portfolio. Readers can learn more about this amazing man and see more of his gallery with a few clicks of their mouse.

* * * * *

After graduating from high school in Toronto and completing a two-year course in mining engineering, 1897-1898, Swannell’s first job in B.C. was as an assistant to a land surveyor in New Denver, probably in the capacity of a chain man. This was during the excitement of the Klondike gold rush which surely appealed to a young man interested in mining.

Instead, he’d found his calling; accepting a job with Victoria surveyors Gore & McGregor, in 1903 and 1904, he acquired his provincial and dominion land surveying licenses. Obviously skilled and ambitious, he hung out his own shingle in 1908 when the building of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was the news story of the day. This was a heady time for many British Columbians, a time when no dream was too big, no project too wild to accomplish if the will and money were there.

Heeding his own call of adventure, Swannell accepted a government contract to survey the Nechako Valley. With transit levels and 66-foot lengths of chain, he and his crew set off by train, stage and sternwheeler to Quesnel where they began a 10-day hike to the Nechako Valley along the Yukon Telegraph Trail.

Beyond civilization, with only the supplies they could carry on their backs or by pack horses, they had to live off the land. Hunting and fishing became as much a part of their daily routine as surveying. By Swannell’s photos, it’s apparent that they ate well!

More government surveys followed: Lillooet, Pemberton, Anderson and Seton Lakes areas; Stuart and Takla lakes; Hazelton and Prince Rupert, with Swannell working out of Victoria which he’d made his home base. Sometimes, worksites were much closer to home: Salt Spring Island and Cowichan Lake’s Gordon River country.

Then back to the Nechako and Endako valleys, this expedition requiring a 400-mile winter sleigh ride.

By 1912 he was surveying the Omineca region, covering no fewer than 1700 miles, most of it by raft. For the first time in the back country, the surveyors enjoyed the novelty of going to and from work in a new fangled automobile.

Impressed with Swannell’s work, Wikipedia tells us, the Surveyor General commissioned him for more surveys of the Nechako and Omineca regions, then the Peace River country from which he and his crew returned to Victoria by way of Alberta, arriving home just in time for Swannell to enlist.

Although 34, married and a father of two, he was off to war in 1915. The army put his map making skills to good use, laying out trenches, and he saw action in the Battle of Festubert. Disabled with a head wound and, it’s suspected, suffering from shell shock, he required several years’ convalescence.

The war was over by the time he returned to active duty so he volunteered for the ill-fated Sibererian Expedition against the Bolsheviks who’d seized control in Russia. Again wounded, he finally returned to Victoria in 1920 to resume his interrupted surveying career, one major assignment following after another, even into the Great Depression.

When, in 1934, the eccentric French industrialist Charles Bedaux approached the Canadian government about staging a trailblazing expedition with Citroen half-tracks across the northern B.C. wilderness, Frank Swannell was assigned to accompany it. (See the Chronicles, ‘Charles Eugene Bedaux and the Champagne Safari.’)

They almost made their goal—2400 kilometres cross-country from Edmonton, AB, to Telegraph Creek, B.C.—but, having continued on horseback after abandoning the Citroens—decided to shut down with the approach of winter. Frank Swannell recorded it all on film.

Besides his many photos over the years, he kept meticulous diaries and field notes and these, too, are now in the BC Archives. What an incredible gift to posterity, they are.

* * * * *

The Charles Bedaux cross-country expedition in the summer of 1934 was more of a publicity stunt than anything else, and was filmed in entirety by a Hollywood camera crew. Land surveyor Frank Swannell, whose official job was to map the land along their route, also recorded the day-to-day routine of the famous ‘Champagne Safari’ on which Bedaux was accompanied by his wife and his mistress. The Citroen half-tracks ended up being abandoned.—BC Archives

Charles Bedaux had known extreme poverty in his youth. He made up for it once he became rich, even when out in the wilderness, as shown in this shot of some of the groceries that were lugged along. —BC Archives

Most off-roaders today have the advantage of using old logging roads. Not so the Bedaux expedition, which had to make its own ‘roads’ as it went, through, over and around the obstacles encountered along the way. When you consider that this was 90 years ago, the Citroen half-tracks did a remarkable job. Did the auto company, owned by a friend of Bedaux’s, get its money’s worth in publicity?—BC Archives

After abandoning the Citroens, the expedition carried on on horseback, by canoe and on rafts. Note the tripod-mounted movie camera on the right. —BC Archives

(Left): After abandoning the half-tracks, the expedition continued on by whatever means of transport available, in this case by raft. When their horses, barely able to find food in the wilderness, began to fail, the expedition was halted. (Right): Swannell and his men had been making rafts when necessary for years, this photo having been taken 10 years before the Bedaux expedition. —BC Archives

Going to work on Stuart Lake in 1910 and 1912. And we complain about driving in commuter traffic. —BC Archives

Portaging across a snow slide in October 1924. —BC Archives

When a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do...in this case build a temporary bridge. Swannell’s caption dates this great photo as being taken in 1902—at the very start of his career as a surveyor. —BC Archives

One of my favourite Swannell shots. Shades of the legendary voyageurs! —BC Archives

Frank Swannell looks to be almost a teenager in this photo. He was 44!

The Swannells, Ada May and Frank, on their wedding day. These two photos are among the few in the Frank Swannell collection he didn’t take himself.—BC Archives